2(22)2019

Anna Horodecka1, Magdalena Śliwińska2

Fair Trade phenomenon: limits of neoclassical and chances of heterodox economics

Abstract

Contemporary research exploring the Fair Trade movement does not provide a clear answer whether the overall impact of Fair Trade is positive or negative and what are the real motives of Fair Trade consumers. In the paper we investigate whether the assumptions of selected heterodox schools (feminist, ecological and humanist) fit better to the reality of the Fair Trade movement than those of the neoclassical theory. Although ‘better fitness’ does not necessarily mean ‘better explanation’, the mismatch with reality may constitute an obstacle in identifying a crucial aspect of the researched phenomenon (i.e. Fair Trade), harming explanation of its existence and development.

Keywords: neoclassical economics, heterodox economics, Fair Trade, poverty, current heterodox approaches, feminist economics, social economics

JEL Classification Codes: A13, F11, F18, F10, B13, B5, B54, B55, B59, I3, Z18

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP.2019.3.1

After WWII in the USA and Western Europe there appeared first initiatives aiming at helping the poorest producers from the Global South through including them into the international trade exchange. The idea based on the principle ‘trade not aid’ has developed and we are currently experiencing an ever-widening presence of the Fair Trade movement. The initiative is experiencing intense growth and includes more and more countries and organizations on both sides of the globe and its goals are widely accepted by societies all over the world and even by international bodies like G8 or the European Commission (Schmelzer, 2007). Contemporary research, however, does not provide a clear answer whether the overall impact of Fair Trade is positive or negative and what are the real motives of Fair Trade consumers, so what are the real reasons for the appearance, development and growth of this movement. We suppose that the reason for this state of affairs can be the lack of an ability of the mainstream economic theory to explain some phenomena occurring in the current global reality.

That is why the aim of this paper is to investigate whether the assumptions of heterodox economics fit better to the reality of the Fair Trade movement than those of the neoclassical theory. We are aware of the fact that the assumptions of one theory do not have to reflect reality 1:1, and that they are purposely simplified. However, at the same time it seems not reasonable to assume something completely contradictory to the basic characteristics of the analysed reality, because it may result in preventing the identification of important causal relationships and characteristics, which may be important for explaining a phenomenon that is relatively new and extremely complex. Adding to this argument the observation that basing on standard theories we cannot explain the existence, development and consequences of this phenomenon in a satisfactory way, here opens the question whether there are some other theories which base on different assumptions that better fit to the reality of Fair Trade.

In order to respond to this question, we have chosen a methodology that is based on the comparison of the basic assumptions made within neoclassical and heterodox economics with goals, assumptions and the essence of the Fair Trade movement. As an example of the heterodox theories we have taken three denominations of the heterodox movement, namely ecological, feminist and humanist economics. The assumptions we made in one theory are the result of its anthropological assumptions (the concept of human nature). These anthropological assumptions have an impact on axiological (values), ontological (the assumptions about the economic reality, for example about the market) and epistemological (strictly: methodological) aspects of the theory.

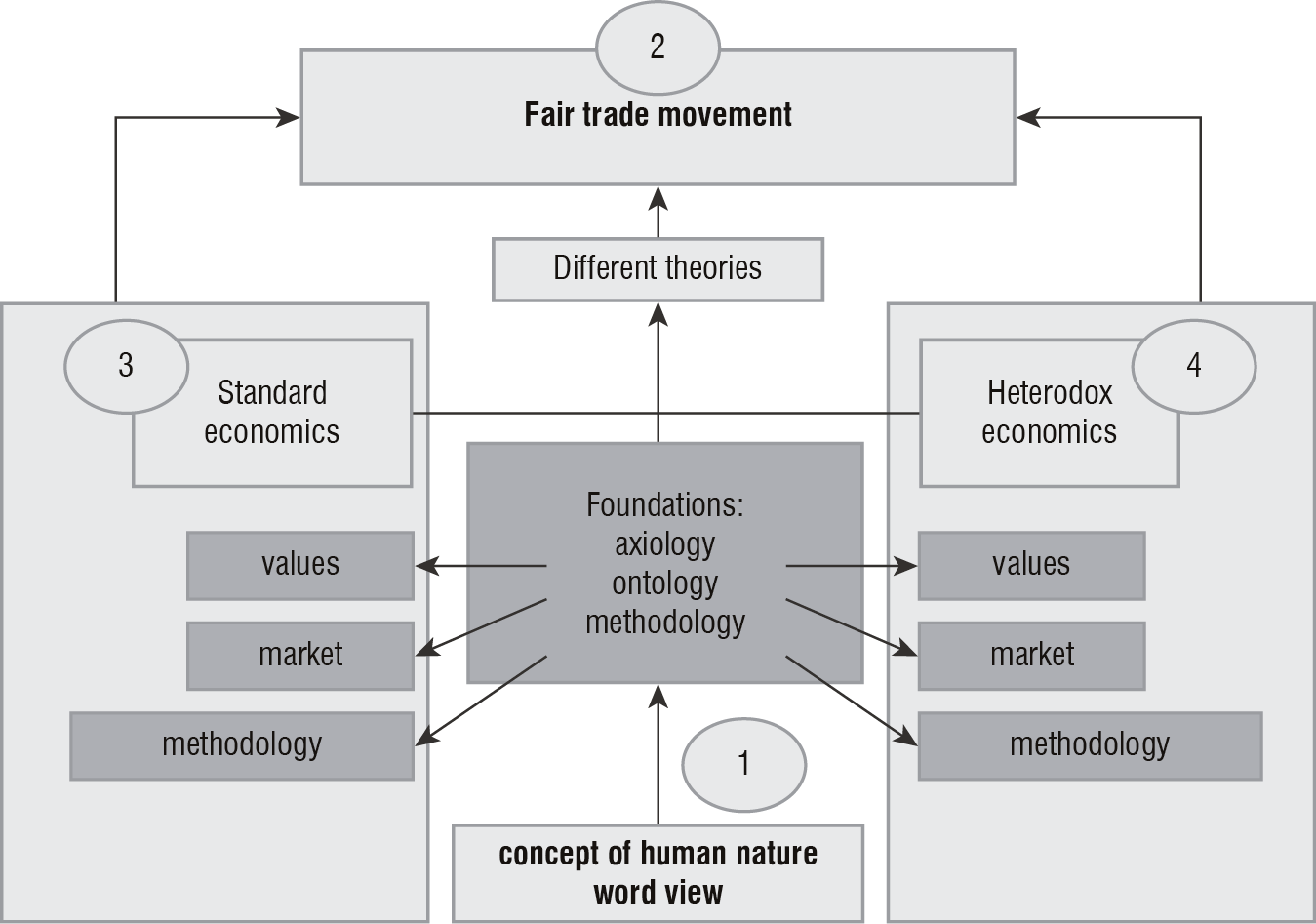

Figure 1 makes our goal more visible. Although the theory (usually used to explain reality) is a visible part of our iceberg, it is built on some assumptions (foundations) of the theory. So, the standard theory (for instance the neoclassical one) is based on assumptions resulting from its concept of human nature – homo oeconomicus, whereas different heterodox denominations result from other anthropological assumptions. These affect their way of defining the values assumed to economic agents – like utility maximisation or efficiency in the case of standard economics (axiological foundations of the theory). Furthermore, they affect the way of perceiving the economic reality in terms of understanding the place of the market in the economic, social and environmental system and its role (ontological aspects). Finally, it influences the understanding of the methodology of research. We claim that these three elements: basic values, the understanding of the market and methodologies are crucial elements which influence the ability or disability of those theories to explain the above mentioned phenomenon. These three areas influence the creation of a certain conceptual apparatus that may hinder or allow us to explain and understand certain real phenomena. That is why it is reasonable to answer the question on the assumption of which theory fits better to the nature of a researched phenomenon.

Figure 1. The structure of the paper

Source: own compilation.

The paper is divided into three sections. After a short presentation of the Fair Trade movement, its main goals, mechanisms of functioning, structure and development (in the first section), we start to look more closely at the assumptions made firstly by standard economics (in the second section) and then selected heterodox economic schools (in the third section) about values, market and methodology evaluating their fitting to the Fair Trade reality, respectively.

The Fair Trade phenomenon

Definition and aims of Fair Trade

Fair Trade is an initiative bringing together conscious consumers, non-governmental organizations and companies involved in international trade aiming at improving the lives of the poor in developing countries. In particular, the aim of the movement is the elimination of social and economic marginalization of poor producers from the Global South, which is to eliminate poverty and promote the concept of sustainable development. According to the first official definition of Fair Trade, formulated in 2001 by FINE3 – an informal cooperation platform of main Fair Trade organizations, “Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. Fair Trade Organizations, backed by consumers, are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade”.

It supports marginalized small producers, whether these are independent family businesses, or grouped in associations or cooperatives, by offering better terms to producers and helping them to organize. It seeks to enable them to move from income insecurity and poverty to economic self-sufficiency and ownership. The aim of this movement is also securing that no child labour and no forced labour is involved in the production of Fair Trade products. Also, high respect for the environment during the whole production process is one of the most important aims and principles of the World Fair Trade Organization.4

Fair Trade is a bottom-up initiative, which should not be perceived as a kind of charity or humanitarian aid. It rather postulates an alternative model of trade relying on permanent, direct relations between local producers from the poor countries of the Global South and consumers living in prosperous Northern countries (Jastrzębska, 2012: 39) and on supporting those societies on the path of development. That is why the Fair Trade movement is based, on the one hand, on the lack of acceptance of consumers from high developed economies for living and consuming at the cost of poorer nations, in particular farmers from Global South countries, and on the other hand, on the acceptance of higher prices of some products in order to support development of those societies, which cannot benefit from the conventional international trade system.

According to Walton (2010), there is no established answer to the question what Fair Trade is, whether it is a project seeking to establish some form of global market justice, whether it is a form of ‘ethical consumerism’ or rather a development initiative. A. Nicholls and C. Opal (2005: 13) state that Fair Trade constitutes ‘a consumer-driven phenomenon’, operating within the liberal trade model and constituting a unique solution to a market failure. M. Anderson (2015: 1) stresses, however, the role of the social movement, which successfully began to indicate political consumerism within its international development campaigns. Such different views reflect in an often posed question, whether Fair Trade constitutes a practical challenge to neoliberal trade and free market or a pure market initiative and a neoliberal solution to market failures (Schmelzer, 2007). Undoubtedly, Fair Trade is about achieving social goals through the market and dynamic development of Fair Trade movements led to the uprising of Fair Trade markets. That is why in this paper the notions ‘Fair Trade initiative’ or ‘Fair Trade phenomenon’ comprise both, the Fair Trade movement and the market.

The evolution of Fair Trade

It can be said that the Fair Trade movement appeared about five decades ago. The initial steps were to build trading partnerships between Fair Trade Organizations – ‘FTOs’ in the USA and Europe and small-scale producer organizations in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In this way the FTOs were hoping to provide poor producers from the South fair access to export markets. In this way they tried to realize the idea of “TRADE NOT AID”, raising consumer-awareness in the North about the unjust and unfair practices and structures in international trade at the same time (Dalvai, 2012). The first ‘Fair Trade’ shop opened in 1958 in the USA, the first Fair Trade Organization was established in 1964 in the UK and in 1967 – the importing organization, Fair Trade Original was created in the Netherlands.

In the 80s and 90s the centre of gravity on the Fair Trade product offer started to shift from handcraft to agricultural goods. In 1973, Fair Trade Original in the Netherlands, imported the first ‘fairly’ traded coffee from cooperatives of small farmers in Guatemala. Meanwhile, Fair Trade coffee became very popular and nowadays, between 25% to 50% of turnover of Fair Trade Organizations from the North comes from this product (WFTO). After the success of coffee, many fair trading organizations expanded their food range and started selling commodity products like tea, cocoa, sugar, wine, fruit juices, nuts, rice and spices.5 While a sales value ratio of 80% handcrafts to 20% agricultural goods was the norm in 1992, in 2002 handcrafts accounted for 25.4% of sales, whereas commodity food lines were up at 69.4% (Nicholls, Opal, 2005).

At the beginning, the movement developed gradually establishing thousands of long-term trading-partnerships and enhancing the awareness of consumers from the North about the situation of producers from the South. Initially, Fair Trade products were sold mainly by ‘Fair Trade Shops’ in the USA and Europe and constituted a niche market. The first World Shop opened in the Netherlands in 1969. In the 1980s, when the interest in Fair Trade products, especially agricultural, started to grow faster, there naturally appeared the need for proving that they are produced according to all principles of Fair Trade. That was the reason for launching the world’s first Fairtrade Certification Mark. It was done in 1988 by the Dutch Foundation Max Havelaar. In the following two decades more and more Fair Trade certifiers and labels emerged in the marketplace (Dalvai, 2012).

Initially, all of them had their own Fairtrade standards, product committees and monitoring systems. In the 90s the process of convergence among the labelling organizations started with its culmination in 1997 when the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO) was created. The FLO constitutes an umbrella organization whose aim is to set Fairtrade standards, support, inspect and certify disadvantaged producers and harmonize the Fairtrade message across the movement. That is why in 2002 the FLO launched a new International Fairtrade Certification Mark, whose aim was to improve the visibility of the mark in supermarkets, facilitate cross border trade and simplify export procedures for both producers and exporters (Śliwińska, 2018: 24). The Fairtrade Certification Mark harmonization process is, however, still underway.

At the initial stage a great role in the development of the Fair Trade movement was played by Christian communities. Even nowadays religious organizations and religious groups are strong supporters of this type of products and are often actively involved in their sale and promotion. For instance, Equal Exchange, a distributor of Fair Trade products in the USA, launched an Interfaith programme, Equal Exchange, which is growing and engages more and more Protestant church organizations and associations. Moreover, in Europe Christian organizations are actively engaged in the promotion and sometimes even in the distribution of Fair Trade products (Claar, 2011: 9–17).

The idea of Fair Trade is also supported by local authorities and various types of local communities. In April 2000 the inhabitants of Garstang, a small town in England, declared their town the world’s first Fair Trade Town. The idea to support Fair Trade by the local community expanded very quickly, not only in the UK, but in the whole of Europe, in the USA and other parts of the globe. For example, the first Fair Trade Town in Italy was Rome in 2005, in the USA – Media (Pennsylvania) in 2006, in Spain – Cordoba in 2008, in Finland – Tampere and in Germany – Saarbrücken in 2009, in Japan – Kumamoto in 2011, in Poland – Poznań in 2012, in Taiwan – Taipei in 2018. Nowadays, there are about 2000 Fair Trade Towns in 30 countries all over the world.6 Towns attempting to call themselves a Fair Trade Town have to fulfil some criteria aiming at the promotion of the broad movement and supporting the sale of Fair Trade products. Meanwhile, the idea of Fair Trade towns expanded to other fields and institutions. Fair Trade Campaigns recognize schools, universities and colleges, scouts, workplaces, religious communities and congregations for embedding Fair Trade practices and principles into their activities.7

The mechanism of Fair Trade

Fair Trade developed specific mechanisms for achieving its goals, which is a combination of guidelines for price negotiation and requirements for certification like (Dragusanu, Giovannucci, Nunn, 2014: 219): price floor, Fair Trade premium, stability and access to credit, working conditions, institutional structure, environmental protection.

–Price floor means that there is a minimum price for which Fair Trade products can be sold even if the market price is lower. It should enable the farmers to cover the costs of sustainable production and it should correspond to the level of a living wage in the sector.

–Fair Trade premium, called also a social premium, is an extra sum of money which is additionally paid by the buyer to the producer groups in order to enable them to invest in projects of their choice – production capabilities or infrastructure, like schools or health clinics.

–Stability and access to credit means that contracts between Fair Trade buyers and sellers are long-term (at least one year or more) and that producer groups are provided by crop financing up to 60 percent.

–Working conditions have to be safe, wages equal to the minimum regional averages and some forms of child labour are prohibited.

–Institutional structure in the form of associations or cooperatives of the farmers enables transparent administration (of e.g. Fair Trade premium) and promotes the process of democratic decision-making.

–Environmental protection means that the Fair Trade production meets the environmental criteria which ensure that the farmers minimize or eliminate the use of less-desirable agrochemicals. That is why certain harmful chemicals are prohibited and the production of genetically modified crops is not allowed (Dragusanu et al., 2014: 220–221).

The structure of the Fair Trade movement

The Fair Trade movement can be perceived as a net of different organizations, firms and communities cooperating with each other in the area of promoting the idea of Fair Trade. The four main Fair Trade networks formed an informal association, FINE (the first letters of their names create the name of the association), constituting the biggest informal platform, coordinating activities of many Fair Trade organizations:

•Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO);

•International Fair Trade Association, now the World Fair Trade Organization

(WFTO);

•Network of European Worldshops (NEWS!);

•European Fair Trade Association (EFTA).

The FLO, often called as Fairtrade International (FI), is an association of producer networks, national labelling initiatives and marketing organizations that promote and market the Fairtrade Certification Mark in their countries. It was divided in 2004 into two independent organizations in order to ensure the transparency and the independence of the Fairtrade certification and labelling system:

•FLO International – developing Fairtrade Standards and assisting producers in gaining and maintaining certification and in capitalizing on market opportunities on the Fairtrade market;

•FLOCert – ensuring that producers and traders comply with the FLO Fairtrade Standards and that producers invest the benefits received through Fairtrade in their development.

The WFTO is a membership organization of over 400 Fair Trade enterprises and the organizations that support them. The WFTO members are social entrepreneurs and artisans, farmers and campaigners, innovators and Fair Trade pioneers spread across more than 70 countries. They work to a business model that puts the needs of people and the planet first. They are fully committed to Fair Trade in everything they do and they truly prioritize the goals of Fair Trade. The WFTO standards look at every aspect of a business and confirm whether it is truly a Fair Trade enterprise. The organization verifies that the entire business and its systems for managing their supply chains have embraced Fair Trade. The WFTO provides spaces for producers, exporters, importers, retailers, and consumers to connect and work together, exchange best practices, forge synergies and speak out for Fair Trade – all working towards a sustainable and fair global economy. As a global network, the WFTO is supported by five regional branches (Africa & the Middle East, Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America & the Pacific Rim) and the office in Culemborg in the Netherlands coordinates the activities of the WFTO worldwide (https://wfto.com).

The EFTA constitutes a network of nine Fair Trade importers/retailers from eight European countries: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Its main goal is to create synergies and to facilitate the cooperation among its affiliates in different areas like trading, exchange of information, labour division, or execution of joint projects in order to increase efficiency and effectiveness of their activities (https://newefta.org).

The NEWS! was established in 1994 as a network of associations of Worldshops from 13 European countries, representing about 2,500 shops. Its goal is to promote the idea of Fair Trade and the development of the Worldshops movement. It initiates and coordinates joint campaigns and awareness raising activities of the European Worldshops, like the annual European Worldshops Day and supports the professionalisation of national associations of Worldshops. In 2008 it became the part of the WFTO-Europe.

In 2012, Fairtrade International’s largest adherent, Transfair USA, announced that it would resign its FLO membership and create a parallel label, Fair Trade USA. One of the most important reasons was a different vision about the ways how to achieve the common goals, in particular whether the Fair Trade label should only be available to small-scale producers. Fairtrade International claims that certification should generally be restricted to small producers and Fair Trade USA believes that large producers and plantations should also be certified (Dragusanu et al., 2014: 218).

Summarizing, it is important to mention that the whole Fair Trade movement embraces different non-governmental organizations including non-profit organizations, enterprises both in the South and in the North, which have to be profitable in order to survive on the competitive market and different communities, including local governments, universities or schools, which engage in supporting the idea.

So, it can function thanks to two groups comprising, on the one hand, importing organizations in highly developed countries, and on the other hand – federations associating small farmers and craftsmen in the Global South. The cooperation between them is the essence of the entire initiative. However, Fair Trade is not a centrally managed network of individual branches, but a set of autonomous organizations that maintain their separateness but agree to comply with the common standards for distributed products (Jastrzębska, 2012: 40).

Discussing Fair Trade it is also crucial to stress that different forms of the notion ‘Fair Trade’ are currently used. ‘Fairtrade,’ in the one-word form, is used by Fairtrade International for their certification mark and for references to their specific market (Dragusanu et al., 2014: 218). ‘Fair Trade’ and ‘fair trade’ are often used as synonyms referring to the whole initiative, although ‘fair trade’ is more often used as a broader notion, including different initiatives and ideas aiming to make the trade ‘fairer’ (and sometimes it is even counterposed to the concept of ‘free trade’). ‘Fair Trade’ in the two-word form refers rather to activities of the above-mentioned organizations promoting this movement and different certification schemes.

Fair Trade growth

Fair Trade is an initiative which in recent years has been rapidly growing in terms of sales, the number of countries and parties involved on the side of consumers in the North and the number of countries and producers in the South. After the introduction of TransFair mark in 1992 (today – Fairtrade mark) and international harmonization of labelling organizations in the 1990 s, Fair Trade has experienced enormous growth rates since the 2000s (Schmelzer, 2007). One of the main reasons was the fact that the mark enabled consumers to identify fairly traded products at mainstream food retailers which, next to the net of Worldshops, engaged in selling Fair Trade products (Bäthge, 2015: 6). According to Annual Report on Fair Trade activities,8 in 2016 global Fair Trade sales reached € 7.88 billion and more than 1.6 million farmers and workers around the globe benefited from Fair Trade. It worked through more than 1,411 certified producer organizations across 73 countries and recorded a significant growth rates in sales of key products: coffee – 3%, cocoa – 34%, sugar – 7%, bananas, tea, flowers and plants – 5% each. Moreover, farmers and workers also received € 150 million in Fairtrade Premium. There are new fast-growing Fair Trade markets like Austria, which in 2016 experienced growth of 46% in Fair Trade retail sales. However, also mature Fair Trade markets like France, the Netherlands, Norway and Switzerland experienced substantial increases in sales in 2016, all with more than a 20 percent growth.

This phenomenon is treated by mainstream economists with a certain distance and one can meet the objections that Fair Trade is the opposite of free trade, does not meet the criterion of efficiency and thus, among others, the chance of achieving its main goal of combating poverty is very small or even non-existing (Paul Collier, 2007; The Economist, 2006; Victor Claar, 2011). The research looking for the answer about the effectiveness of Fair Trade concentrates mostly on questions whether Fair Trade producers get higher prices (Bacon, 2005; Méndez et al., 2010; Weber, 2011), whether Fair Tarde provides greater financial stability for farmers (Bacon et al., 2008; Méndez et al., 2010; Dragusanu, Nunn, 2014), whether the selection to become a Fair Trade producer is positive or negative (Sáenz-Segura, Zúñiga-Arias, 2009) and how it influences the problem of measuring the effects of Fair Trade, what are the consequences of opening the system for all producers (de Janvry, McIntosh, Sadoulet, 2012) or what are the consequences for non-Fair Trade producers (Dragusanu, Nunn, 2014). On the other hand, researchers are looking for real motives of Fair Trade consumers (Sama, Crespo-Cebada, Diaz-Caro, Corlos, 2018; Hwang, Kim, 2018) for paying higher prices (Hainmueller, Hiscox, Sequeira, 2011; Arnot, Boxall, Cash, 2006; Hiscox, Broukhim, Litwin, 2011). There is, however, no consensus in the literature about the effectiveness and ability of Fair Trade to achieve its goals. Meanwhile, this initiative is developing both in terms of sales volumes and product range and in terms of opening for cooperation with other social movements. The reason for this situation may be different theoretical approaches used by scholars investigating Fair Trade.

Fair Trade in the context of standard economics

In this section we try to answer whether the ontological, axiological and methodological foundations of neoclassical economics create the right grounds for explaining by neoclassicists the emergence, existence and rapid development of the Fair Trade movement. We claim that values, the way of understanding of the market (which is related to the values) and available methodologies determine the ability of a theory to explain different phenomena, in this case the Fair Trade phenomenon. That is why in the current section we follow this structure, looking at the neoclassical values, the understanding of the market and methodologies from the perspective of the Fair Trade movement aims and functioning.

Values

Neoclassical economics is based on a couple of values which are embedded in its concept of human nature – the homo oeconomicus (Horodecka, 2017b; Rost, 2008). This concept is interrelated with some fundamental values – which we can call: efficiency, utility or profit maximization and competition. Taken together, they provide the understanding of rationality, which is much more than the value (rational choices are preferred to non-rational), and is rather an implicative assumption.

The fundamental value is efficiency. This value plays in neoclassical economics a similar role as the word ‘good’ in ethics. This means that it is treated as the litmus paper to all economic phenomena. This value has implications for the understanding of other crucial concepts of neoclassical economics which, as some feminist economists stress, is value-laden, too9 – namely rationality. Only efficient solutions of an economic problem and choices maximizing utility are considered to be rational. And what we mean here is not only efficient solutions in the sense of Pareto but about all choices in which we move on the production-possibility frontier – it means we use the lowest cost for producing the same unit of the product. How do we achieve this result? Neoclassical economics introduces a value here – utility, which constitutes a motivation for such a rational choice.

On the side of the producer, the value motivating to act is profit maximization, and on the side of the consumer – utility maximization, searching for these results which bring the greatest possible utility. We can find approaches to measure utility, for instance by Jeremy Bentham who provided some examples how to precise this concept (utility as pleasure, a hierarchy of pleasures, the role of time) but later economists abandoned the possibility of measuring it and they took it as something that does not necessarily have to be explained and is not comparable (for instance Pareto).

The third value – competition – is related to the notion of the market mechanism. It is assumed that economic actors compete with each other to get more resources and so to find a better final result – greater utility or profit and the market is an institution allowing free competition, thanks to which the most efficient distribution of resources is possible (the price is determined by the market mechanism).

Do these values provide a good basis for the understanding of the Fair Trade phenomenon? First of all, the idea of the Fair Trade movement does not fit into the world of the above-mentioned values, because it attempts to help farmers who are not able to compete on the global market. Because of the basic value – efficiency – standard economics is inclined to provide answers, whether the Fair Trade mechanism works efficiently, whether it enhances efficiency of poor producers or whether it is efficient to support Fair Trade or not from the point of view of the global economy, developed and developing countries or to what extent this idea can be treated as a remedy for market failure, similarly to the practice which we encounter in Western economies, where support of the SME sector is justified by this very reason.

The aims of Fair Trade do not fit into the value of efficiency. Fair Trade is not developed (as e.g. SMEs are) in order to make profit but in order to provide justice, reduce income inequalities, fight poverty and its role cannot be limited to enhancing efficiency. It improves well-being and gives chances to join the international trade exchange, which can solve some of the stability problems of developing countries, but it is not efficient in the sense of Pareto as soon as the costs of this action are taken over by western consumers.

Is it difficult to assess whether the values of utility and profit maximization can constitute a proper basis for explaining the existence and development of the Fair Trade movement, as it consists of many entities having a common goal, but driven maybe by different motives. Taking as an example the side of consumers, it is doubtful whether the concept of utility maximization enables the full understanding of Fair Trade consumers’ behaviour, because the Fair Trade consumer voluntarily resigns from the higher utility curve (by limiting its consumption or paying more money for the same number of products) and moves to a lower one just to let someone else in the world jump to a higher utility curve (and increase his or her consumption). Explaining such a consumer behaviour using the concept of utility maximization would imply the necessity of the extension of the notion ‘consumer utility’ and perceiving it as a broader concept, not related only with the physical characteristics of products, or even a brand that guarantees a certain level of quality and hedonistic motives of the consumers, but rather also with non-material characteristics of products, production process and ‘higher’ needs of the consumers, which goes beyond the common understanding of consumer utility.

It is difficult to assess whether the value of profit maximization is the driving force of Fair Trade producers. The answer to this question would require further research, but it seems that especially in the case of people fighting with hunger and extreme poverty, the motivation for economic activity is survival, education and broader development rather than profit maximization. Similarly, the mission of the distributors from the North is not to maximize utility but to help the poorest farmers from the South and provide Western consumers with high quality products from the South. Nevertheless, they perceive the necessity of profitability (but not necessarily maximization but maybe satisfaction) which rather builds constraints of their activity but cannot be understood as a primary goal. From this perspective, competition is the reality in which their business activities are embedded, rather than a value on which it is based. However, this dilemma concerns many enterprises functioning on the market.

The value ‘competition’ helps to understand the behaviour of companies which compete, among others, by the way of reducing costs of their activity – labour and capital costs. It is not the case for Fair Trade, which is focused not on minimizing labour costs, but on enhancing them beyond the market-established wages in order to allow the labour force to live a worthy life. Fair Trade distributors do not pay higher prices for goods in order to get more quality of labour and increase the value of products neither to raise motivation to work but to enable the farmers and employees to approach goals beyond, again, both utility and efficiency reasons. Summing up, one can say that values crucial for neoclassical economics do not fully suit the reality and the essence of the Fair Trade movement, which can be the reason for difficulties of fully and properly explaining the Fair Trade reality and growth using the neoclassical theory tools.

The understanding of the market

The market in standard economics is understood as a unique mechanism which provides efficient solutions and allows for reaching best results for all of the economic agents. There is no need, therefore, to embed the market. On the contrary, it is the market which provides values for society. It is assumed that basing on these values, not only economic but also social problems can be explained as for example Gary Becker tries in his approach (Chicago School).10

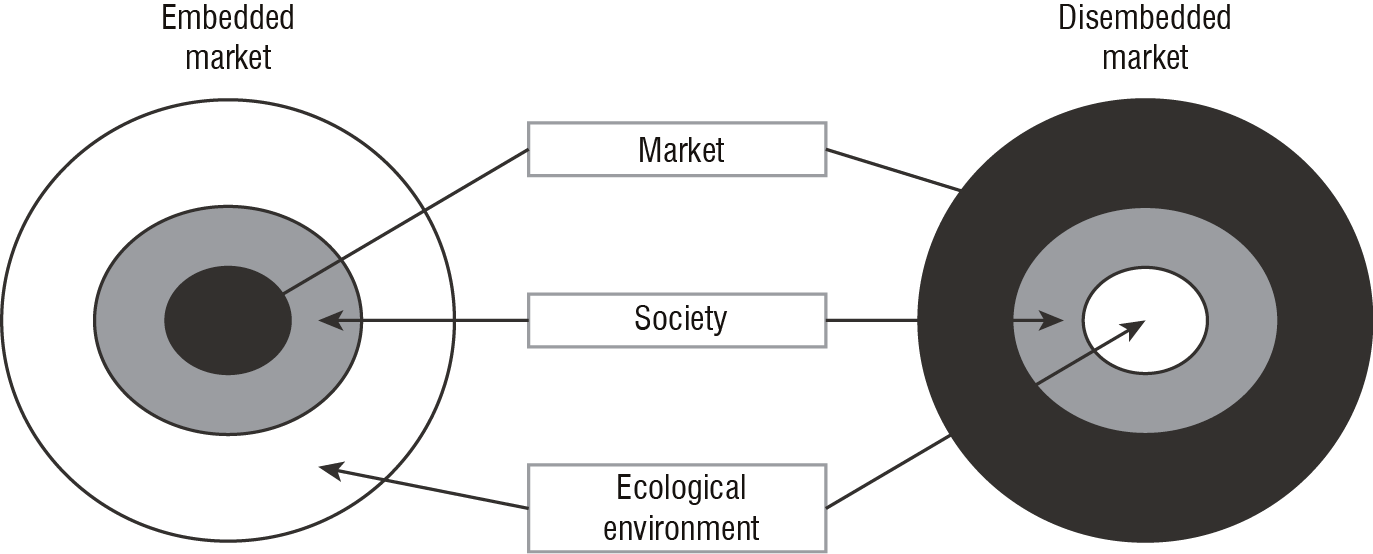

The idea is thus that the market is not embedded, separated from society and from ecology. The values of the market are even extrapolated on other aspects of society. This reflection is presented in Figure 2 (in the next section), which demonstrates how the understanding of the market dominates over social, ethical and ecological systems.11 It is not implied by this statement that people have to act according to these values (normative consequences), but that assuming these values, we can explain better (positive function of science) the economic phenomena. It is proved by some experiments that people confronted with homo oeconomicus are more eager to behave according to the assumptions of this model (Schechner, Zsok, 2007). So, although the values of homo oeconomicus have only positive functions, they may become normative (Manstetten, 2002) and influence the behaviour of economic agents, which in turn may have a negative impact on the economy (Siebenhüner, 2001; Brockway, 2001). So, for instance if somebody is convinced that people behave as a homo oeoconomicus does, acts in a less cooperative way than somebody who believes that people are social beings. Eventually, people assuming the homo oeconomicus concept by other people have lower moral competencies (Turek, Wojtczuk-Turek, 2011), and social competencies (Horodecka, Martowska, 2013; Siebenhüner, 2000; Kapeller, 2008) provide further examples of a negative impact of economic man on the public awareness and politics. This may be e.g. harmful for the economy, as long as lacking cooperation raises transactional costs which the company has to bear then – and that has a negative impact on efficiency.

The neoclassical understanding of the market may, therefore, limit the possibility of explaining the Fair Trade phenomenon because the ideas which are the basis of this phenomenon and which lead to its development come from fundamental ideas of society such as solidarity, fairness, human dignity, sustainability and not from values generated by the market like competition or efficiency. These ideas guide organizations and their stakeholders and can be understood as a bottom-up movement changing step by step the expectations of consumers and the whole society from economic activities and from the market.

Methodology

The methodology proposed within neoclassical economics relies on the idea that major hypotheses of research are derived from the theory and then verified empirically considering the concepts and terms of selected theories. As long as the major theories in standard economics refer to some aggregate variables or other variables operationalized numerically, neoclassical economists are more focused on using formal methods and models in their research and there can be observed their growing share in mainstream economics even after the 2008 crisis (Oliveira, 2018).

This way of research may be insufficient for the analysis of the Fair Trade phenomenon for a couple of reasons. Firstly, such a contextful phenomenon as Fair Trade implies the knowledge about both the situation of developed countries (which cannot be reduced only to the knowledge of GINI index and some aggregate variables) and the motives of the consumers of Fair Trade products and institutions supporting the movement. It can be very difficult or even not possible to embrace such a complex phenomenon with formal methods.

Secondly, the Fair Trade phenomenon is a relatively new issue and needs, in order to be researched and in order to put relevant hypotheses, some explorative research which usually can be done with the help of qualitative methods like interviews, document analysis, in-depth analysis of the situation, or as Kaja refers to – descriptive analysis (Kaja, 2015; 1992), which is not deriving hypotheses from the current theoretical framework but trying to learn as much as possible from the current phenomena. Kaja gives some examples referring to his experience with Japan’s economy and economists, who in order to explain the problems with their agricultural sector do not just switch to the existing theories but try to understand the problem deeper, viewing as well the existing institutional setting of the problem and so finding the possible reasons for its inefficiency. It was not the free market lacking but on the contrary, the separation of property from representation in local governments. Why it is so? Fair Trade can be perceived as a reaction to the growing inequalities. The inequality issue can be perceived as a relatively new phenomenon, which is maybe much more dependent on some institutional factors than on some economic laws. The variety of situations and cases (different countries, different agricultural production, different environmental and weather conditions, different history – colonial but not only) make it difficult to create a common denominator for quantitative research and comparisons that would be meaningful.

Another reason is that formal methods (and especially those that the neoclassical methodology which bases on linear relations and one point of balance) are not the best solution when the problems studied are characterized by a high degree of complexity. Undoubtedly, the Fair Trade phenomenon is extremely complex and combining non-profit organizations whose mission is to help the poorest with profit-oriented enterprises contains the problem of relations between business and the public sector and all the dangers for both sides. It may be difficult to capture questions like why such phenomena as FT appeared, exist and develop using those methods.

Heterodox economics assumptions

and the Fair Trade phenomenon

In this section we analyze the basic assumptions of heterodox economics and compare these assumptions with the reality of the Fair Trade phenomenon, trying to answer whether these assumption match better the phenomenon of Fair Trade than neoclassical assumptions do. We take as an example ecological economics, humanist economics, and feminist economics.

Generally speaking, the diverse axiological, ontological and methodological assumptions which create the foundations of the analyzed denominations of heterodox economics result from the diverse assumptions about the economic actor (concepts of human nature). This in detail means diverse understanding of values (axiological basis) which guide the behaviour of the economic actor and an alternative view on the market (ontological assumptions).12 Different than neoclassical assumptions about economic agents, their values and the alternative perception of the market affect the methods considered as appropriate for the analysis of economic phenomena.

Values

The different assumptions about human nature taken by heterodox economics schools result in a much broader range of values than it is the case in neoclassical economics. Although there are many differences within heterodox economic schools, they have many values in common. The table below (Table 1) provides some insight into the understanding of the concept of human nature as the source of values – taking as an example feminist, ecological and humanistic economics.

Table 1. The concept of human nature in selected economic schools as the source of their axiological foundations

|

Economic schools |

Dimensions of the concept of human nature |

Resulting values referring to micro- and macro-level of economics |

|||

|

Individual |

Social |

Ontological |

Micro-level |

Macro-level |

|

|

Neoclassical economics |

utility egoism individual preferences |

competition |

norms (efficiency), disembedness and expansionism of the economic system |

efficiency, competition, utility (hedonism) |

redistribution in the sense of Pareto |

|

Ecological economics |

real needs (not: preferences) sustainability, happiness |

cooperation |

norms (responsibility, fairness), dependence on the natural system, entropy |

fairness, cooperation real needs, good life as a source of values |

sustainability, fairness, even at the cost of economic growth, de-growth |

|

Humanist economics |

self-development altruism needs not wants, dual-self13 |

altruism, solidarity, common good |

norms (dignity solidarity), divine/moral |

equality between man and women, altruism especially in form of care |

supporting equality, caring sector, social provisioning, sustainability |

|

Feminist economics |

different motives (altruistic and selfish) basic needs social provisioning |

gender, equality dependence on others altruism and egoism |

individuals’ dependence on the cultural social and ecological environment |

development of individuals and society, the hierarchy of needs, freedom (2 meanings) |

common good, small-scale, basic needs & capabilities |

Source: Horodecka (2018a).

So, in heterodox economics a person’s value is not only competition but cooperation as well, and the place of utility maximizing as the value is restituted by fairness and satisfaction. This is the case of humanist economics, where it is assumed that each person has equal rights for the freedom of choice (Sen, 1999; 2018), feminist economics, which stresses the necessity to combat each discrimination not only of women but minorities as well (Ferbe, Nelsom, 1997; 2011) and ecological economics, where utility maximization is put in frames of justice towards other people, future generations and nature (Daly, 1997; 2011). These normative expectations towards economic agents are a starting point to think about the economic reality where the state and institutions are expected to build such frames for the functioning of the market and so intervene in economic actions so that these basic freedoms and justice may be guaranteed. The mentioned heterodox economic approaches result from the ethical conviction that fairness is desired by individuals, and even if individuals often prefer fair to the optimal solution, their individual actions are not sufficient and, therefore, fairness should be implemented by formal and nonformal institutions and the state.

This leads us closer to the Fair Trade problem, which can be understood as basing exactly on the conviction of people that fair is good, and in this sense on the value of fairness. Therefore, people accept higher prices in order to buy products on which they ‘lose’ in order to support fairness. Moreover, the tendency to build further institutions supporting the Fair Trade movement is exactly the response of the conviction that the market is not sufficient and that in the name of fairness the state or other institutions have to undertake actions.

Moreover, the discussed heterodox approaches replace the strict assumption of neoclassical economics that egoism is the basis of the efficiency of the market with the other one – stressing that altruism is as well necessary and makes cooperation possible, which allows the economic system to work. So, it is, according to heterodox economics, neither true nor necessary that a person calculates his/her choices only on the basis of utility. An individual neither can do it under real conditions (for example because of limited cognitive capacity, lacking full information), nor it would help the individual in order to be satisfied. We need both egoism and altruism to be able to survive not only as an individual but as well as society (for instance by constructing sustainable economy).

Fair Trade consumers pay usually more than the market price for a particular level of quality of chocolate, coffee or another product. If we would like to explain this phenomenon using the neoclassical tool of ‘consumer utility maximization’, then one should take an additional assumption about altruistic preferences constituting the concept of ‘consumer utility’ extending this notion far beyond its common sense. It may be easier and more fruitful to explain the behaviour of Fair Trade consumers assuming man’s altruism and wish to do something good for another person quite selflessly.

Last but not least, heterodox economists replace the neoclassical concept of preferences with the concept of needs. Needs, according to ecological, feminist and most of all humanist economics, cannot be reduced to the concept of preferences, as long as there is a difference in the need for ‘having a house’ or ‘enough to eat’ or ‘having a job’ and the need to buy a luxurious yacht or the third house. The first sort of needs constitutes basic needs, which allow, according to Amartya Sen (1999), man to realize basic functionalities and so to improve their well-being. According to humanist economics, too much consumption can limit even the possibilities of individual development. So, generally speaking, heterodox economists go beyond the rule of impossibility of comparison of utilities (Pareto optimality) and solve the problem by leaving apart the problem of utility and replacing it by differentiating and defining explicite some basic needs which cannot be satisfied only by private goods. This is the case with feminist economics (with its consequence to understand economics as the science about social provisioning (Power, 2004; Jo, 2011). This is as well true for humanist economics, which bases on the differentiation between needs and wants (Lutz, Lux 1979; 1988), developed from the concept of needs by Maslow (1943; 1970). And finally, the concept of needs is fundamental for ecological economics, where it is assumed that the quality of a person’s life depends on the possibility of satisfying fundamental needs such as survival, feelings or identity (subsistence, affection, and identity) (Max-Neef, 1991; Horodecka, Vozna, 2017). However, there are various ways to satisfy them, which are determined by culture and circumstances (such as a certain type of food or employment), certain rights and abilities or through interactions with others (Dodds, 1997: 103–104).

Finally, we can say that the values on which heterodox economics is based come most of all from the social or even ethical system and so base more on the social and political values than only on the economic ones. So, whereas the values of standard economics are derived from the economic system, the heterodox values come from the outside of the market and mirror the values important for political and social systems (like cooperation, fairness, and even social altruism necessary to build up the common good). Such an observation builds a link toward the next topic – the way of understanding the market by heterodox economics.

Summarizing, how can we relate the values of heterodox economics to Fair Trade? Are they more compatible with the Fair Trade phenomenon than the values constituting the basis for neoclassical economics? As we have stated before, Fair Trade is to understand from the perspective of solidarity and cooperation, which are stressed by the selected heterodox schools. Similarly, Fair Trade is based on the idea of fairness and the appreciation of each human life, equality of persons in their right to approach happiness. These are values which are intrinsic in all the considered schools (see: Table 2). Similarly, the concepts of the hierarchy of needs and distinguishing the needs from wants can be very useful in explaining different dimensions of the Fair Trade phenomenon, especially the behaviour of consumers from the North (e.g. meeting wants as an obstacle of human progress) and different short-term and long-term effects of this initiative in the Global South countries in terms of economic and social development (e.g. the meeting of basic needs as a condition for progress).

Embedded market – social

The market within heterodox economic schools is perceived as embedded in the social as well as political system which should represent the values of society. Ecological economics, and to some extent humanist and feminist as well, embed the market also in the ecological environment.

The analyzed heterodox schools treat the market differently than standard economics does, not as a unique and most important component and the alpha and omega of the economy but as the embedded system. The market is in this sense not a mechanism which works similarly to natural systems according to some laws which we can discover (demand, supply) but it is embedded socially and ecologically. Therefore, economic processes cannot be explained according to heterodox schools only by these ‘economic’ laws but it is necessary to consider the context – the existing social and ecological circumstances and institutions.14

The market, according to Herman Daly (2011; 1997), the representative of ecological economics – is and should be ecologically and socially embedded and has to (normative goals) aim at sustainability and fairness. Feminist economics embeds the market in social values like gender equality, representing the ethical consideration of society. Humanist economics, whose roots are grounded, among others, on the book of F. Schumacher (1972), which appeared timely close to the Report of Club of Rome, stresses not only social values, but ecological sustainability as well. Similarly, Lutz, Lux (1976; 1988) are enhancing the role of both systems – ecological and social as the context of economic action.

Figure 2 presents the idea of embedding the market in social and ecological system as contrasted with the disembedded market. This means that the values of the market are subordinated to the values of major systems as well and not as in standard economics, where the values of the market dominate over other systems.

The idea of the embedded market may be helpful for approaching the Fair Trade phenomenon. It makes it possible to explain the Fair Trade phenomenon without the necessity to prove the advantages of it and motives neither to economic growth nor utility. It is enough to show that it may help to reduce inequality of income, enhance fairness, and help to improve the well-being of the less privileged groups of the society (even if at the cost of other groups paying more for the products – losing in the sense of Pareto). Moreover, actually it is that the Fair Trade movement is an economic endeavor working under the auspices of societal aims and convictions.

Figure 2. The embedded and disembedded market

Source: Horodecka (2011; 2018) integrating the ideas of Daly (2011).

Methodologies

Heterodox economics opens new ways to thinking about the methodology of economics. It is not only understood positively but normatively as well. There are also other expectations of the methods used in order to call them scientific. While standard economics is focused on predictive power of models and methods used, heterodox economics (most of all referring to the three selected schools) is more focused on understanding and explaining economic phenomena in order to actively change reality and in this sense is more normatively oriented.

The different ontologies of these schools – standard economics as a disembedded economic system and heterodox as an embedded result to a different extent of considering the role of the context. While standard economics focuses on the creation of universal laws,15 heterodox economics, basing on different ontological assumptions, negates the possibility of explaining the economy by means of equations, numbers, and especially linear models, opening more space for qualitative research.

Ecological economics uses, for instance, a pluralistic (Forstater, 2004) and transdisciplinary approach to examine its scope. It tries to overcome the dichotomy of a positive and normative approach, and for some economists its approach is described as post-normal (Funtowicz, Ravetz, 1994; 1993). The methodology and research methods of ecological economics speak for its orientation towards the normative approach. And so, it considers, for instance, building of visions as a key method (Meadows, 1996: 117) – a rational process of imagining the transition from the state to the desired state (ecological sustainability) (Prugh, Costanza, Daly, 2000: 41).

Also, feminist economists do not agree with the positivist understanding of science and look for other than formal methods. They strongly recommend the importance of empirical research, but advising it, the focus lies on field research in which the context plays a key role. As a consequence, they do not rely only on quantitative measures, but include qualitative research, cooperation with other disciplines and the use of data collected by them (Schneider, Shackelford, 2001). Feminist economics, which is concerned about the lack of validity of many abstract and formal models based on aggregate data (which do not consider the context, setting), recommends alternative techniques that sound ephemeral at first glance, i.e. reflection (Bergmann, 1987), empirical observation and complex verbal explanations of real economic problems, and consideration of Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM).

Finally, humanistic economics seeks first of all to solve practical problems that the society is currently facing (within a given cultural context), guided by established values. It adopts two principles as the starting point of its methodological considerations. The first one concerns human needs, constituting the basic foundation of human values and distinguishing them from wants. The second relates to life (Lutz, Lux 1979; 1988), i.e. the reference of economic phenomena to human life understood as development, which results in an innovative approach to work (Schumacher, 1973) and jobs (Restakis, 1991). Two other values – complexity and balance – can be derived from the principle of life and impact the way of analysing economic phenomena. In the method of analysis, there is a similar conviction about the bimodality of economic reality, which in this case consists in the conviction that the analysis of the outer world should be accompanied by the discovery of the inner world.

How may these methodologies of the analysed heterodox schools be of use for the analysis of the Fair Trade phenomenon? First of all, the fact that heterodox economics focuses more on the normative side of the theory creates space for analysing phenomena whose scope is to “make the world better” and looking for solutions which are more congruent with the values of societies (in the eyes of the society as a whole they are considered as better and more desirable). Such an approach is crucial and constitutes the basis for researching the Fair Trade phenomenon, not only because it allows for the analysis about the causes of this movement, but because it also creates space for the analysis how to make it function better in the sense of achieving its goals. All the schools mentioned above also emphasise the importance of qualitative methods of economic phenomena because of their substantial complexity. The vision, predictions and creating scenarios as the key method in ecological economics seem to be very useful for Fair Trade analysis, because in the changing global market environment the needs of the poor in the Global South can change over time. Moreover, the whole idea of the Fair Trade movement is based on the vision about more fair conditions for trade for less developed countries and the poorest communities in the world. So, visions, predictions (“what can happen, if nothing changes” or “how can the whole global economy develop better, if inequalities between states were smaller”) and making scenarios (“different ways of achieving these goals”) seem to be very useful for Fair Trade analysis.

Feminist economics seems to deliver some useful methodological approach as well, especially in unmasking assumptions and stressing the necessity of research on the individual context of most economic situations. The Fair Trade movement is a very differentiated phenomenon, and it has diverse characteristics depending on a product or country. That is why stressing by feminist economics the individual context of similar economic phenomena and using reflection and empirical observations seem to be highly appropriate for analysing Fair Trade.

Also, humanist economists deliver some useful methodological approaches for Fair Trade analysis, in particular looking for solving practical problems that the society is currently facing within a given cultural context and distinguishing the human ‘need’ form the ‘wants’. This distinction sheds a new light on consumer behaviour, which is a crucial element of Fair Trade, ae well as on the behaviour and needs of the poorest people in the South.

Finally, ecological economics, by focusing on the assumption of ecological embeddedness of the economic system, moves our attention back from the focus on economic growth in the direction of even de-growth. It allows for viewing Fair Trade in the context of sustainability goals and not so much tries to justify its existence by the focus on economic growth. Furthermore, by stressing the role of creating visions in thinking about economic problems, it provides more tools to consider the role of Fair Trade – its existence and development and its lack for the whole economic system.

***

The aim of this paper was to investigate whether the assumptions of heterodox economics fit better to the reality of the Fair Trade movement than those of the neoclassical theory. We based our analysis on the conviction that assumptions of reality far from the phenomenon researched may significantly impede seeing and identifying the important features of the investigated/observed reality. We claim that three elements: basic values, the understanding of the market and methodologies influence the creation of a certain conceptual apparatus of a theory that may hinder or allow explaining certain real phenomena and processes occurring in the global economy.

Our research has shown that the idea of Fair Trade does not fit into the world of the values of standard economics as profit and utility maximization, efficiency and competition are not the principles on which the movement is based. On the contrary, Fair Trade can be an example that human activity, even business one, can be caused and driven by other, contradictory values like solidarity and limitation of one’s own utility in order to help other people, fairness and cooperation. Perceiving the market as a universal mechanism independent from the social, cultural and ecological environment and affecting the values recognized by society contradicts the Fair Trade phenomenon, which constitutes a proof that societies recognize some values like the need for more equalities, fairness, sustainability or common good and therefore, have some concrete expectations towards the market and in this way influence the way the market works. Deriving major hypotheses from the theory and verifying them empirically, considering the concepts and terms of selected theories and using mostly formal quantitative methods and models may limit the possibilities of standard economics of exploring such a new and complex phenomenon like Fair Trade.

Our research confirmed that the assumptions of heterodox economics seem to be closer to the Fair Trade reality than neoclassical ones. The values on which heterodox economics is based come most of all from the social or even ethical system, so one can say that they come from the outside of the market and mirror the values important for political and social systems. Basing on the values like altruism, fairness, cooperation, good-life, equality, sustainability, heterodox economics build on the same foundations and conviction as the Fair Trade movement, namely that the market should serve the development of people and that people may have specific expectations from the market and economy, which derive from the values shared by respective communities and entire societies. So, we can say that the heterodox concept of the market embeddedness to a high extent reflects the fundamental principle of the Fair Trade movement. Although we cannot tell whether the more reality-close assumptions will necessarily lead to better explanations, we can still claim that they allow us to identify more characteristics and processes of Fair Trade than by using very simplified assumptions of neoclassical economics, which in the case of Fair Trade, as demonstrated above, are even contradictory to that what we observe in the Fair Trade movement.

Heterodox economics is more focused on understanding and explaining economic phenomena than neoclassical ones, which put an accent rather on prediction. That is why the methodologies used by those schools like qualitative methods, the descriptive approach, contextual analysis, discourse analysis, case studies, visions and creating scenarios may be very useful in explaining such a new and complex phenomenon as Fair Trade, challenging very difficult and important economic, social and political problems. Moreover, the fact that heterodox economics focuses more on the normative side of the theory causes it to create space for analysing phenomena which focus on “making the world better” and looking for solutions which, according to the values of societies, are better and more desirable. Such an approach is crucial and constitutes the basis for researching the Fair Trade phenomenon, not only because it allows for the analysis about the causes of the appearance of this movement, but because it also creates space for analysis, how to make it function better in the sense of achieving its goals.

The findings of this paper may contribute to the further research on Fair Trade movements and markets. They show the fact that the assumptions of the neoclassical theory may constitute an obstacle in understanding the real nature of Fair Trade and research based only on such assumptions may lead to inappropriate conclusions about the future developments. Our findings are also important for policy makers, as there is an ongoing discussion about whether, how and to what extent the Fair Trade movement and the Fair Trade product market should be supported by the government. Fair Trade as a grassroots movement aims at counteracting social problems through the market mechanism. Better understanding of the real nature of this phenomenon may help to decide whether it would be better to support such an initiative through the extension of the legal framework for the functioning of the market with some basic Fair Trade principles or rather to support more directly the development of the Fair Trade product market through different policy instruments.

References

Anderson, M. (2015). A History of Fair Trade in Contemporary Britain. From Civil Society Camoaigns to Corporate Compliance. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Arnot, C. P., Boxall, C., Cash, S. B. (2006). Do Ethical Consumers Care About Price? A Revealed Preference Analysis of Fair Trade Coffee Purchases. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 54 (4): 555–565.

Bacon, C. (2005). Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Can Fair Trade, Organic, and Specialty Coffee Reduce Small-Scale Farmer Vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua?. World Development, 33 (3): 497–511.

Bacon, C. et al. (2008). Are Sustainable Coffee Certifications Enough to Secure Farmer Livelihoods? The Millennium Development Goals and Nicaragua’s Fair Trade Cooperatives. Globalizations, 5 (2): 259–274.

Bäthge, S. (2015). Executive summary: Final report “Does Fair Trade Change Society?: TransFair e.V. (Fairtrade Deutschland).

Becker, G. S. (1993). Der ökonomische Ansatz zur Erklärung menschlichen Verhaltens (Einheit der Gesellschaftswissenschaften). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Bergmann, B. (1987). Measurement’ Or Finding Things Out in Economics. Journal of Economic Education, 18 (2), 191–201.

Brockway, G. P. T. (2001). The End of Economic Man: An Introduction to Humanistic Economics. New York: W. W. Norton.

Claar, V. (2010). Fair Trade?: Its Prospects as a Poverty Solution. Acton Institute.

Colander, D., Holt, R., Rosser, B. (2004). The Changing Face of Mainstream Economics. Review of Political Economy, Taylor and Francis Journals, 16 (4), 485–499.

Collier, P. (2007). The Bottom Billion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Costanza, R. (2001). Visions, values, valuation, and the need for an ecological economics. Bioscience, 51 (6), 459–468.

Dalvai, R. (2012). The Metamorphosis of Fair Trade. Fair World Project, 7–8. Retrieved from www.fairworldproject.org; [http://fairworldproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/FWP_Fall_publication_2012__Page_08–09.pdf

Daly, H. E. (1997). Beyond growth: the economics of sustainable development. New York: Beacon Press.

Daly, H. E., Farley, J. (2011). Ecological economics: principles and applications. Washington: Island Press.

De Janvry, A., McIntosh, C., Sadoulet, E. (2012). Fair Trade and Free Entry: Can a Disequilibrium Market Serve as a Development Tool? Unpublished paper, Berkeley: University of California.

Dodds, S. (1997). Towards a ‘science of sustainability’: Improving the way ecological economics understands human well-being. Ecological Economics, 23 (2), 95–111. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0921–8009 (97) 00047–5

Dragusanu, R., Giovannucci, D., Nunn, N. (2014). The Economics of Fair Trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28 (3), 217–236.

Dragusanu, R., Nunn, N. (2014). The Impacts of Fair Trade Certification: Evidence from Coffee Producers in Costa Rica. http://scholar.harvard.edu/nunn/publications /impacts-fair-trade-certification-evidence-coffee -producers-costa-rica

Duchin, F. (1998). Structural Economics. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Fairtrade International. https://www.fairtrade.net

Ferber, M. A., Nelson, J. A. (1993). Beyond economic man: feminist theory and economics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ferber, M. A., Nelson, J. A. (2003). Feminist Economics Today. Beyond Economic Man. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Forstater, M. (2004). Visions and scenarios: Heilbroner’s worldly philosophy, Lowe’s political economics, and the methodology of ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 51 (1–2): 17–30.

Funtowicz, S., Ravetz, J. (1993). Science for the post-normal age. Futures, 25 (7): 739–755.

Funtowicz, S. O., Ravetz, J. R. (1994). The Worth of a Songbird: Ecological Economics as a Post-normal Science. Ecological Economics, 10 (3): 197–207. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0921–8009(94)90108–2

Hainmueller, J., Hiscox, J. M., Sequeira, S. (2011). Consumer Demand for the Fair Trade Label: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Unpublished paper.

Hewitson, G. J. (1999). Feminist economics; interrogating the masculinity of rational economic man. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hiscox, M. J., Broukhim, M., Litwin C. S. (2011). Consumer Demand for Fair Trade: New Evidence from a Field Experiment using eBay Auctions of Fresh Roasted Coffee. Available at SSRN: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3 /papers.cfm?abstract_id=1811783.

Homann, K., Blome-Drees, F. (1992). Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Horodecka, A. (2015c). The impact of the human nature concepts on the goal of humanistic economics and religious motivated streams of economics (Buddhist, Islam and Christian). Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali. Vita e Pensiero, Pubblicazioni dell’Universita’ Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 123 (4): 413–445. doi:RePEc:vep:journl:y:2015: v:131: i:4: p:413–445

Horodecka, A. (2016). The Impact of the Concepts of Human Nature on the Methodology of Humanistic Economics and Religious Motivated Streams of Economics (Buddhist, Islam and Christian). In: M. H. Bilgin, H. Danis (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics, vol. 2, Proceedings of the 15th Eurasia Business and Economics Society Conference (pp. 515–545). London: Springer.

Horodecka, A. (2017b). The methodology of evolutionary and neoclassical economics as a consequence of the changes in the concept of human nature. Argumenta Oeconomica, 39 (2), 129–166. doi:10.15611/aoe.2017.2.06

Horodecka, A., Vozna, L. (2017). A new paradigm of economic policy based on the synthesis of orthodox and heterodox economics Research Papers of the Wroclaw University of Economics / Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 489: 137–148. doi:DOI: 10.15611/pn.2017.489.12

Hwang, K., Kim, H. (2018). Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness, Journal of Business Ethics, 151 (2), 579–598.

Jastrzębska, E. (2012). Korporacje transnarodowe a Fair Trade. Kwartalnik Kolegium Ekonomiczno-Społecznego Studia i Prace / Szkoła Główna Handlowa, 4: 29–49.

Jo, T.-H. (2011). Social Provisioning Process and Socio-Economic Modeling. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 70 (5): 1094–1116. doi:DOI: 10.1111/j.1536–7150.2011.00808.x

Kaja, J. (2015). Eseje o Japonii i metodologii deskryptywnej. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH.

Lutz, M. A., Lux, K. (1979). The challenge of humanistic economics. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co.

Lutz, M. A., Lux, K. (1988). Humanistic economics: the new challenge. New York, NY: Bootstrap Press.

Maslow, A. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4): 370–396.

Max-Neef, M. (1991). Human Scale Development: Conception, Application and Further Reflections. New York and London: Apex Press.

Meadows, D. (1996). Envisioning a sustainable world. In R. Costanza, O. Segura, J. Martinez-Alier (Eds.), Getting Down to Earth. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Méndez, V. E. et al. (2010). Effects of Fair Trade and Organic Certifications on Small-Scale Coffee Farmer House- holds in Central America and Mexico. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 25 (3): 236–51.

Nelson, J. A. (2001). Economic methodology and feminist critiques. Journal of Economic Methodology, 8 (1): 93–97. doi:10.1080/13501780010023252

Nicholls, A., Opal, C. (2005). Fair Trade: Market-Driven Ethical Consumption. London: Sage Publications.

Oliveira, T. D. (2018). From Modelmania to Datanomics: The Top Journals and the Quest for Formalization. STOREP Conference 2018 – Whatever Has Happened to Political Economy? Università di Genova, June 28, 2018 – June 30, 2018.

Power, M. (2004). Social Provisioning as a Starting Point for Feminist Economics. Feminist Economics, 10 (3): 3–19. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000267608

Prugh, T., Costanza, R., Daly, H. E. (2000). The Local Politics of Global Sustainability. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Restakis, J. (1991). Humanizing the Economy. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Rost, N. (2008). Homo oeconomicus. Eine Fiktion der Standardökonomie. Zeitschrift für Sozialökonomie, 45 (158–159): 50–58.

Sáenz-Segura, F., Zúñiga-Arias, G. (2009). Assessment of the Effect of Fair Trade on Smallholder Producers in Costa Rica: A Comparative Study in the Coffee Sector. The Impact of Fair Trade, edited by Ruerd Ruben: 117–135. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Schmelzer, M. (2007). Fair Trade – In or Against the Market? Dreigliederung, Institut fuer Soziale, www.threefolding.org/essays/2007–01–001.html (15.06.2018).

Schneider, G., Shackelford, J. (2001). Economics standards and lists: Proposed antidotes for feminist economists. Feminist Economics, 7 (2): 77–89.

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: a study of economics as if people mattered. London: Blond and Briggs.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

Sen, A. (2008). Capability and Well-Being. In D. Hausman (Ed.), The Philosophy of Economics (pp. 270–293). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Siebenhüner, B. (2000). Homo sustinens — towards a new conception of humans for the science of sustainability. Ecological Economics, 32 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1016/S0921–8009(99)00111–1x

Svendsen, G. T., Svendsen, G. L. H. (2009). Handbook of social capital: The troika of sociology, political science and economics. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Śliwińska, M. (2018). Geneza i kierunki rozwoju ruchu Fair Trade. Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach, 372: 20–34.

Walton, A. (2010). What is Fair Trade? Third World Quaterly, 31 (3): 431–447.

Weber, J. (2011). How Much More Do Growers Receive for Fair Trade-Organic Coffee?. Food Policy, 36 (5): 678–85.

World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO). https://wfto.com

1 SGH Warsaw School of Economics

2 Poznan University of Economics and Business

3 http://fairtrade-advocacy.org/about-fair-trade/what-is-fair-trade/193-what-is-fair-trade (accessed: 3.07.2018).

4 https://wfto.com/fair-trade/10-principles-fair-trade (accessed: 2.07.2018).

5 https://wfto.com/about-us/history-wfto/history-fair-trade (accessed: 3.07.2018).

6 http://www.fairtradetowns.org

7 https://spolecznosci.fairtrade.org.pl

8 https://annualreport16–17.fairtrade.net/en/

9 For instance, Ferber & Nelson (1993; 2003) and especially Hewitson (1999) accentuate here the masculine character of homo oeconomicus which impacts as well the particular understanding of rationality which enhances masculine traits. Whereby Nelson (Nelson, 2001) discusses the impact on such assumptions on the methodology.

10 “I came to the conclusion that the economic approach is so capacious that it can be applied to all human behavior” (Becker, 1993). The social and ecological problems can be, according to Gary Becker, as well explained by the logic and values dictated by the market. Even ethical issues and problems (according to e.g. to Karl Homan – Homann & Blome-Drees, 1992) should and can be solved basing on the assumption that the economic actor is a U-maximilizer.

11 In the sense that ethics can be considered as a part of values on which society is built.

12 The understanding of the role of the market is as well the consequence of a different worldview which builds part of the concept of human nature (ontological one, see the model of the concept of human nature, Horodecka, 2017b).

13 Higher self which strives for needs and lower self who aims at wants.

14 The problem of ‘laws’ in economics and if they are necessary and sufficient to understand economic phenomena is discussed by Hardt (2018).

15 Hardt (2017) discusses if it is possible or even necessary to build economics on the idea of universal laws.