3(27)2020

Anna Anetta Janowska1, Radosław Malik2

Digitization in museums:

Between a fashionable trend

and market awareness

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to verify how museums in Poland deal with the challenge of digital transformation. The proliferation of information and communications technology (ICT) enables the digitization of museum collections and increases their availability to the public. The preservation and popularization of cultural heritage, being an important part of the cultural policy, is a priority for the European Union, resulting in increased funding of digitization initiatives. The study presented in this article is based on a survey performed among a group of leading museums in Poland which are recorded in the State Register of Museums. The results show that museums accept digitization as a crucial element of their activity. 69% of the institutions present some part of their collections online and 94% intend to increase the scope of digitization. However, most institutions share less than 25% of their current collections online despite having a larger part digitized. 83% of museums share their collections exclusively on their own websites or dedicated platforms, and most institutions (62%) observe a positive connection between sharing collections online and the number of physical visits to the museum. The results also show that museums tend to prioritize heritage preservation over collection sharing.

Keywords: museum, digitization, future museum, digitized collection, digital heritage, cultural policy

JEL Classification Codes: Z10, Z11, Z18

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2020.3.2

Cyfryzacja w muzeach: między modą a świadomością rynkową

Streszczenie

Celem artykułu jest zbadanie, w jaki sposób muzea w Polsce reagują na wyzwania związane z postępującą cyfryzacją. Rozpowszechnienie się technologii informacyjno-komunikacyjnych (ICT) sprzyja cyfryzacji kolekcji muzealnych i zwiększa ich dostępność dla publiczności. Zachowanie i popularyzacja dziedzictwa kultury jako jeden z ważnych elementów polityki kulturalnej jest jednym z priorytetów Unii Europejskiej, co przekłada się na zwiększone finansowanie działań cyfryzacyjnych. Badanie przedstawione w artykule jest oparte na ankiecie przeprowadzonej wśród wiodących w Polsce muzeów wpisanych do Państwowego Rejestru Muzeów. Wyniki pokazują, że muzea uważają cyfryzację za istotny element swojej działalności. Spośród instytucji 69% udostępnia część swoich kolekcji online, a 94% ma zamiar poszerzyć zakres cyfryzowanych zbiorów. Jednak większość udostępnia poniżej 25% kolekcji w sieci, chociaż posiadają o wiele więcej zasobów już scyfryzowanych. Na własnych stronach lub stronach dedykowanych projektowi cyfryzacji udostępnia kolekcje 83% muzeów, zaś 62% obserwuje pozytywny związek między udostępnianiem kolekcji online i liczbą fizycznych wizyt w muzeum. Wyniki pokazują również, że muzea wciąż są bardziej skoncentrowane na zachowaniu dziedzictwa, a nie na dzieleniu się nim z publicznością.

Słowa kluczowe: muzeum, cyfryzacja, muzeum przyszłości, scyfryzowana kolekcja, dziedzictwo cyfrowe, polityka kulturalna

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: Z10, Z11, Z18

Introduction

“The internet is today what electricity used to be in the last century: a big accelerator of innovation” (Museum of the Future…, 2019). Digital transformation has impacted every sector of the economy (Malik, 2018; Malik, Janowska, 2018, 2019), not only reinforcing significant development but provoking profound crises as well. Every branch of the cultural sector adopted the use of the internet in a manner appropriate for its characteristics (Janowska, 2017). In the domain of the museum, this has resulted in the adoption of new functions and tasks (Góral, 2012) reflecting, inter alia, shifts in cultural consumption patterns (Navarrete, 2013b).

The purpose of the article is to verify how museums in Poland deal with the challenge of digital transformation. We investigated how collection digitization is performed and viewed by the decision makers in museums. The study is based on a survey conducted among a group of leading museums in Poland recorded in the State Register of Museums. Moreover, we investigate the connection between the efforts undertaken by Polish museums and the goals of the European Union (EU) in regard to cultural policy.

A prominent number of studies on museum and library digitization (Navarrete, 2013a; Paolini, Mitroff Silvers, Proctor, 2013) have revealed that museums face a significant challenge while applying new digital technologies. The alleged inability to benefit from the technological advances in digitization is part of a broader stream of the literature discussing the causes and possible solutions to the crisis in museology that is claimed by some museologists (Zawojski, 2005).

Chronologically, in the 1980s, computers were introduced to support catalogues and collection management systems (Schmitt, Meyer-Chemenska, 2015), which was followed by the stream of more elaborate usages aimed at the improved utilization and conservation of cultural heritage (Guccio, Martorana, Mazza, Rizzo, 2016). At the turn of the millennium, due to the proliferation of both devices (personal computers and, most recently, smartphones) and internet access (broadband and mobile), information and communications technologies (ICTs) mainly supported access to information on cultural goods and their distribution. Thus, related to the sharing economy concept, the sharing of cultural goods became one of the key promises of a future which envisaged, among other things, the sharing of collections and online spaces, as well as digital connections with new audiences; even those geographically remote (Guccio et al., 2016; Museum of the Future…, 2019). Therefore, two goals of museum transformation with the support of digitization have become particularly prominent: convenient and accessible collection sharing, and the creation of an otherwise-impossible user relation network, to transform the traditional space of the museum into a museum of the future (Andreacola, 2014). These goals are related to the more traditional public museum mission to “create a sense of national identity, encourage respect for other cultures and cultural diversity, foster an understanding of the past and teach aesthetic values” (Towse, 2010: 237), which reflects the major objectives of the cultural policy, namely: preserving the cultural identity of the nation, ensuring equal access to culture, promoting creativity and high-quality cultural goods and services and ensuring cultural diversity in order to respond to the needs and tastes of all social groups (Ilczuk, 2002). To fulfill this museum mission with the support of digital transformation, one of the key instruments of the cultural policy i.e. public funding, representing important investments, has been applied by various countries as part of their cultural policy strategies.

The argument in this paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we present challenges museums have been facing in the digitized world as well as opportunities they could take advantage of. Secondly, we picture diverse European and Polish strategies undertaken under the cultural policy, aimed at supporting various cultural heritage initiatives, mainly digitization. Thirdly, we describe the research method and the sample, and finally, we discuss the results of the study.

Museums in the digitized world

Museums have been saved from the most draconian digital technology-induced consequences that have affected certain cultural sectors, such as the recording or film industries which suffered particularly from the effects of “informal circulations of culture” (Filiciak, Hofmokl, Tarkowski, 2012), commonly known as “piracy” (Liebowitz, 2013; 2014; 2017). The museum’s core resources, belonging to the physical world, remained unchanged and safe in their showrooms or storage areas. One may even claim that the digital transformation brought about unprecedented opportunities to this sector, namely greater encouragement for audiences to visit physically the museum’s premises, motivated by appealing information accessed on the internet. Equally, museums have enjoyed larger numbers of online visitors remotely admiring collections and benefiting from the expert information on museums’ web pages. However, these opportunities were accompanied by a series of challenges museums needed to face, such as a widening range of available entertainment and cultural offers for consumers, combined with the shrinking free time and attention (Citton, 2014; Citton, Crary, 2014) consumers could devote to respective leisure activities (Borowiecki, Prieto-Rodriguez, 2015).

Alongside this (r) evolution came an important switch in consumer preferences and consumption patterns (Navarrete, Borowiecki, 2016; Potts, 2014) concerning the demand for new forms of cultural goods, as well as ways and speed of accessing and consuming them. A significant number of consumers, especially young people, increasingly expect a large variety of goods, including cultural heritage, to be readily available via home computers (Wallach, 2001) and/or personal mobile devices. Consequently, “the traditional tripartite basis of the museum – the collection itself, its educational function, and the professionalization of competences – is increasingly destabilized. Therefore, an increasing number of museums are asked to become cultural centres and social capital producers” (Greffe, Krebs, Pflieger, 2017: 319). On the one hand, museums have been confronted with an uncommon opportunity to see their traditional audience augmented significantly, which, in the era of an important economization of culture, is not without significance. On the other hand, they have been exposed to a real danger in mutual misunderstanding between them and their public, as well as a serious mismatch when it comes to the new expectations and behaviors (Konach, 2017).

The evolution of the behaviors, needs, and preferences mentioned above, however, is not only the result of technological progress, but above all, of the global socio-cultural changes referred to as “postmodernity” or “liquid modernity” (Bauman, 2008). In a world of constant change, nothing remains stable or predictable. The role of historical cultural heritage, and thus that of museums, gains importance in such circumstances, as it was pointed out by the Council of Europe, which should entail evolution in the cultural policy strategies. According to the Faro Convention adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in 2005, preserving cultural heritage brings social and economic benefits by helping to achieve sustainable development, build social capital and the feeling of belonging, as well as contribute to creativity, social cohesion and ideals, principles and values resulting from the experience of past conflicts and efforts to make progress (Pasikowska-Schnass, 2018).

Cultural policy strategies in Europe and in Poland towards cultural heritage

The European Commission has devoted great attention to the preservation of cultural heritage by funding a substantial number of projects to connect and give access to heritage materials since the 1980s (Borowiecki, Navarrete, 2017). Among them, one can find initiatives such as the European Capitals of Culture, launched in 1985, Raphaël, started in 1995, the Culture 2000 framework program running from 2000 to 2006, or the European Heritage Label initiated in 2013. In the recent Europe 2020 Strategy, defining objectives for the growth of the European Union by 2020, “digitisation and preservation of Europe’s cultural memory which includes […] museum objects […] is one of the key areas tackled by the Digital Agenda for Europe” (European Commission, 2011), constituting one of its seven pillars. Cultural resources are considered as input for added-value products and services whose role should be to inspire innovation in a number of fields, namely tourism, education, advertisement or gaming (Digitisation of Cultural Heritage, nd). By that means, tourists and new businesses, attracted by the online accessibility of the museums’ collections, are supposed to favor local and regional development. Moreover, the digitization process itself should create new employment opportunities in creative and technology sectors.

Highlighting the benefits for European countries, and particularly their economies, the Commission Recommendation cited above invited Member States to become involved in the digitization of the cultural materials, including museum collections, archives, libraries, and audio-visual content. The estimated cost of this process was 100 billion EUR over 10 years, 2011–2021, of which digitization of eligible collections in the 17,673 European museums was estimated at 38.73 billion EUR. The cost related to preserving and providing access to the digital resources over the 10-year period following digitization was calculated separately and was planned at the level of 10 to 25 billion EUR (Digitisation of Cultural Heritage, nd), “provided that centralised repository infrastructure was made available for the purpose” (Poole, 2010: 1).

Since then, reports have shown constant progress in respective countries relative to the digitization project. According to the 2015 Enumerate report (Enumerate, 2015), on average, 23% of collections were digitally reproduced and 50% were scheduled to undergo the process. Obviously, it has been highlighted that some institutions have not been able to adopt digital technologies and maximize their support for the information economy (Borowiecki, Navarrete, 2017).

Research has revealed that in 2017 a 4% decline was observed in items digitally available on cultural heritage institutions websites, in favor of social media platforms such as Europeana or Wikipedia (Pasikowska-Schnass, 2018). The EU Member States report initiatives to encourage cultural institutions as well as publishers and other rights-holders to make digitized material available on Europeana. A number of online data aggregators were also established in most of the Member States (European Commission, 2016). According to a study by Brinkerink, Dutch heritage institutions have published over half a million objects on Wikimedia Commons, which represents about 2.4% of all Wikimedia content (Brinkerink, 2015). Such an attitude constitutes an example of the institutions’ exceptional awareness of the importance of sharing digitized collections on the most popular and frequently used aggregation platforms.

In Poland, several initiatives have been implemented to support digitization in museums. The digital transformation of museums was one of the priorities implemented under the government program Culture+ (Kultura+), running between 2011 and 2015. Its goal was to offer all the society members the widest possible access to cultural heritage and scientific achievements by building digital collections (Digitalizacja w muzeach, nd). Since 2016, the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage has also been operating the Digital Culture program, aiming at digitizing cultural heritage, providing access to digital resources and allowing their re-use for promotional, educational and scientific purposes (Kultura cyfrowa, 2017). Another project, E-museums, launched in 2013, was devoted to supporting digitization processes in museums as well (O projekcie, 2013). Digitization of cultural resources was also foreseen in the Digital Poland Operational Programme 2014–2020, axis II: E-administration and open government, in specific objective 4: Increase in availability and use of public sector information (sub-measure 2.3.2: Digital sharing of cultural resources). The expenditures allocated to these measures were of about 500 million PLN (almost 120 million EUR) (European Commission, 2016). According to the report by the Polish Supreme Audit Office (Najwyższa Izba Kontroli), the cost of the digitization conducted between 2011 and 2014 by museums, archives, and libraries was of almost 200 million PLN (about 47 million EUR), constituting 8.4% of the total 2.4 billion PLN (560 million EUR) allocated between 2009–2020 by the Ministry of Culture and Digital Heritage’s budget for digitization (Digitalizacja dóbr kultury w Polsce, 2014).

As of 2018, the majority of the museums participating in the Kultura+ program, interviewed by the authors of the report Common Good, Passion and Practice: Digital Cultural Resources in Poland, had shared less than 50% of their digitized collections online, principally on their own websites (Bosomtwe et al., 2018). Although the museums’ attitudes towards sharing their resources bear signs of progress and acceptance towards wider accessibility for new, online audiences (Bosomtwe et al., 2018), a significant number of them remain reluctant. Moreover, it has been suggested that museums continue to give priority to collection development and protection over meeting the general public’s new needs and consumption habits (Misiak, 2017).

Research method

The aim of the study concerning the digitization of museum collections was to determine the premises, scope and results of this process in the leading museums in Poland recorded in the State Museum Register, and to compare the results with the previously mentioned studies. Run by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, the register covers 129 entities with collections of special importance for culture and national heritage – due to the scale of the operation and the value of the collections, as well as representing a high substantive level. The research covered all the museums present in the current version of the register.3 This characteristic prevents them from being representative of all the museums in Poland, as a greater degree of collection digitization can be expected in the sample than in the general population of museums in Poland. Nevertheless, the analysis of leading institutions can reveal the general attitude of Polish museums towards the challenges of the future.

It has been observed that in the digitized collections research area, questionnaires, interviews and data logging were the methods most commonly applied for empirical research, with most common method being questionnaires (Kabassi, 2017). Therefore, the questionnaire was chosen as a primary research method in the empirical section of this study.

The main study was carried out within 14 days, from July 4, 2018 to July 18, 2018. It was conducted using the online questionnaire method, preceded by telephone contact established in order to verify the mailing list as well as to provide the museum staff with basic information about the purpose of the study. The online questionnaire consisted of 11 single and multiple-choice questions, in which the first ones referred to the digital availability of collections in the audited entity. Positive answers led to further questions concerning the premises, scope, and results of the exhibit digitization. Negative ones redirected to question number 10, relating to digitization plans over the next three years, and number 11, which asked about the main obstacles to digitization. Of the 129 surveys sent, only 35 were returned, which constitutes 27% of the sample and thereby a sufficient part to be considered representative of the selected group of museums. The answers obtained were not only compared within the scope of each single question asked in the survey, but also crosschecked among questions in order to draw additional conclusions from answers given by the museums.

Findings and discussion

Museums in Poland constitute the research population for our study. The sample included 129 museums in the State Register of Museums, which includes the leading institutions in Poland. All of the museums in the register were contacted with the online questionnaire and a letter stating the purpose of the research. We received 35 complete surveys, which translates to a 27% positive response rate.

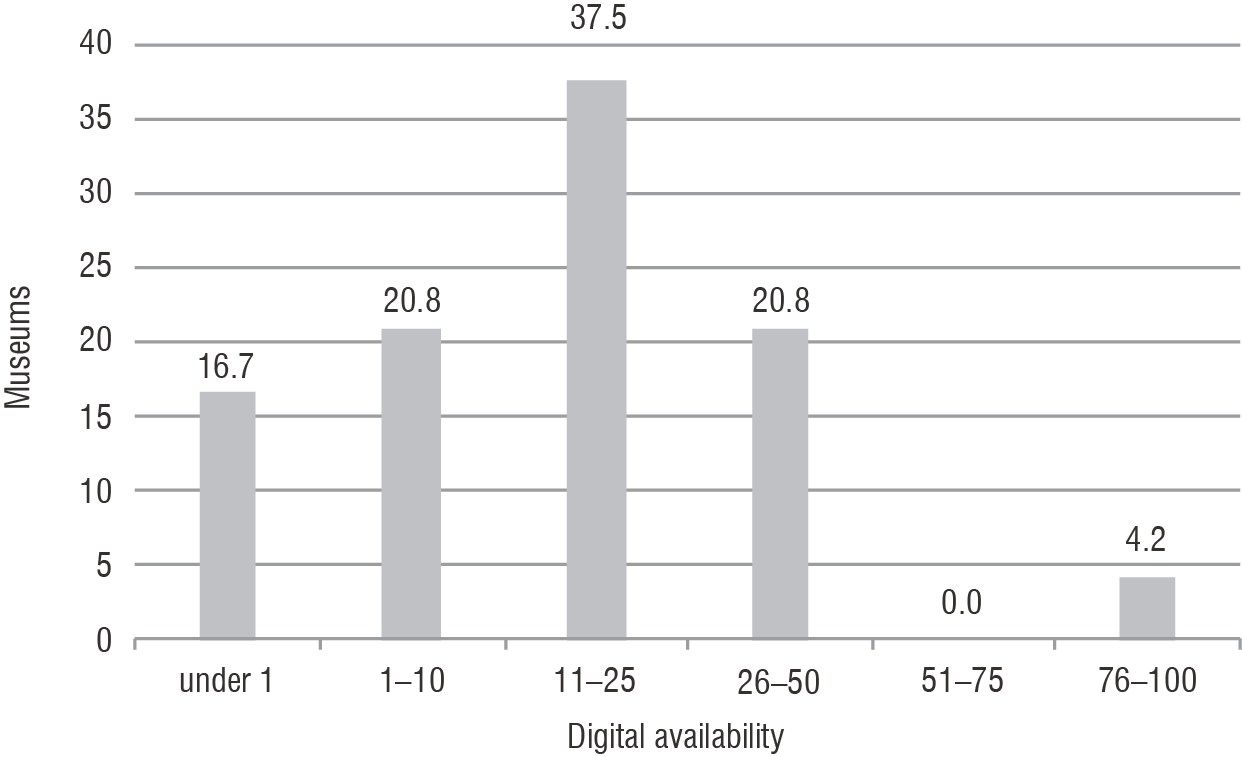

The results of our study show that the leading Polish museums accept the postulate that digitization is a crucial element of their activity in the evolving socio-cultural environment influenced by intense changes in technologies. This attitude is supported by the results of the question about collections available digitally. 24 institutions declared that some part of their collection is available online, which constitutes 69% of the total answers. However, the scope of digitization itself is rather narrow. The answers are illustrated in the chart below.

Only one institution (4.2% of the sample) declared that it had digitized between 76% and 100% of their collection. The largest part, i.e. nine museums (37.5%), marked the interval between 11% and 25%. The same number of respondents, i.e. five institutions (20.8%) indicated the ranges between 1% to 10% and 26% to 50% of their total collection digitally available. The above results show that the digitization level of Polish museums corresponds to the European average, which was revealed in studies run by the European Commission (Navarrete, 2013; Poole, 2010; Enumerate, 2015). Moreover, our results reveal the consistent intention among these institutions to increase the extent of their collection digitization in the near future. Only one institution among those without digital collections does not intend to digitize them. Similarly, only one museum among those that have digitized less than 1% of their collection declined to continue the digitization process.

Figure 1. The number of museums in Poland in % and the estimated amount of the entire museum’s collection digitally available (in %)

Source: own research.

In our study we also investigated the main obstacles discouraging these institutions from digitizing their collections. Among the answers provided by the respondents, a lack of sufficient financing, organizational difficulties related to digitization, as well as technical difficulties were pointed out as being of major importance. The attitude towards difficulties is shared among the entire group as similar difficulties were mentioned by the museums that had not started digitization as by those well-advanced in the process. The museums stated that they struggle with the lack of financing (47% of the answers), the organizational difficulties of digitization (31%) and the technical difficulties (22%). None of the respondents indicated the three remaining answers as main obstacles in the process – namely, the lack of conviction that digitization is useful, the lack of expected effects of digitization, or the lack of interest in collections. Such a uniformity of replies proves once again a high awareness among the leading museums about the importance of digitization. However, the answers concerning financial difficulties seem contrary to the substantial public expenditures allocated in diverse national and European programs, which was highlighted in the previous section of the article. One may speculate the extent to which this could be attributed to the information gaps concerning funding sources, the high complexity of procedures in such programs, or other barriers to entry into these programs that may result in a reluctance to get involved. Despite all the constraints, as many as 50% of the institutions invested their own funds to digitize their collections, 42% used EU funds for this purpose, 4% – funds from the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, and 4% – from local authorities’ funds.

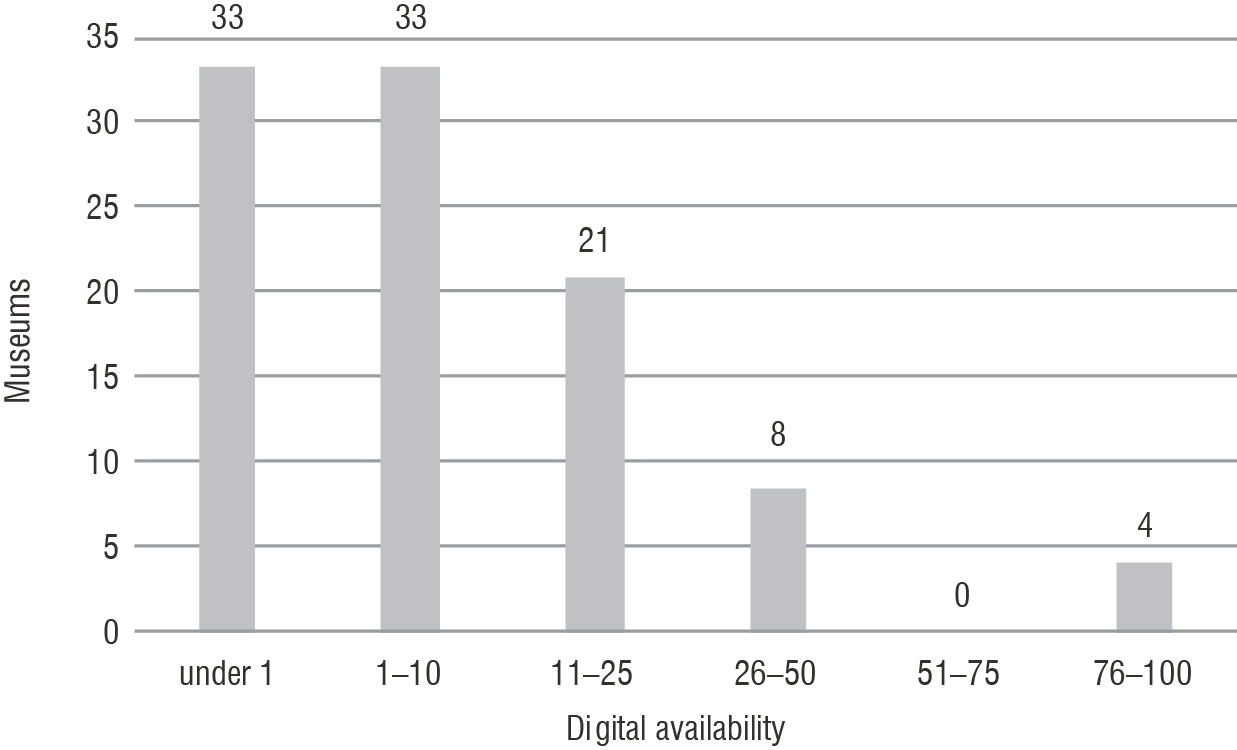

Even though certain financial investments as well as organizational efforts were made to digitize parts of the collections in respective museums, only a small percentage were shared with the public in a digital form, which is illustrated in the chart below.

Figure 2. Currently estimated percentage of collections digitally available to the public (in %)

Source: own research.

Most institutions shared less than 10% of their collections online, and half of these declared making less than 1% available. One institution among those stating a digitization level of 76%–100%, made their entire collection available to the public. The data from Figure 1 and 2 is in striking contrast and suggests that a large part of collections has been digitized but is not presented to the public online. The causes of this discrepancy have not been analyzed in the study and they open an interesting avenue for further scientific research.

Our research also investigated motivations for digitizing collections. This could be especially important, as 94% of institutions expressed the expectation that the scope of their collection digitization will increase in the near future. As far as their primary motivation was concerned, 42% of the institutions expressed a willingness to make their collections more widely available to the public. The desire to preserve cultural heritage was highlighted as a motivation by 29% of the institutions, whereas the desire to make the collections more attractive – by 13%. The remaining institutions indicated a willingness to make their collections more widely available to researchers (8%), and the availability of funding (8%) as reasons for digitization. These answers show an increasing awareness among museums of the concept of resource sharing, as well as an understanding of the contemporary public’s needs and expectations. In light of our findings, the conclusions of the study concerning management in Polish museums (Misiak, 2017), cited previously, are slightly less pessimistic.

Making the collections more accessible and making them available in a more attractive form could imply greater institutional efforts to use various dissemination channels, such as Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons, as well as aggregation platforms – namely Europeana or the Google Art Project. Nevertheless, our study shows that the majority of museums, namely 83.3%, share their collections only on their own websites or on dedicated platforms created especially for the purpose of digitization. One museum, apart from its own website, uses three channels: Wikipedia – as a platform to disseminate information about the digitized collection, aggregation platforms, as well as the Google Art Project. Moreover, this institution declared having digitized 1%–10% of its collection. The museum that has digitized 76%–100% of their collection disseminates it only on its own pages. Aggregation platforms such as Europeana are used by four institutions (16.7%), whereas digitization as a form of improving the attractiveness of the visit is utilized by three institutions (12.5%).

An important part of online collection proliferation is monitoring the activity, which allows for a more active management of the content. Moreover, monitoring the online usage of museum resources could provide further insight into the connection between digitization and physical visits to the museums. While it could be expected that making collections available online would increase the overall appeal of the institutions, going online in a radical way could generate fears that a significant number of visitors may switch to online exploration at the cost of visiting the museum itself.

Our research shows that only 58% of the institutions monitor the use of shared resources by the internet audience. This includes the institution that has digitized between 76% and 100% of its collection, as well as the one with the largest number of channels for proliferating its collection. At the same time, 14 institutions (58%) state that they observe a positive, albeit moderate, connection between sharing collections online and the number of physical visits to the museum. One museum (4.2%) describes this relation as very positive (more visitors), whereas one (4.2%) as moderately negative (fewer visitors). Eight institutions (33.3%) do not notice such a relation, however half of them neglect traffic monitoring on their collection website. One should bear in mind that the responses provided by the investigated institutions remain intuitive, as the museums did not indicate great interest in studying the impact of their digitization efforts on physical visits. These results correspond to the answers obtained in the study about management in museums, run in 2017, showing that in general, museums neglect regular surveys about their present or potential audience due to both insufficient knowledge about research techniques and a lack of interest in social research as part of their activities (Misiak, 2017: 83).

* * *

With initial technophobia relative to highly risky and over-hyped innovations requiring an unfamiliar up-skilling of the workforce (Parry, 2013), accompanied by the fear of losing visitors, museums finally understand the importance of technology in diverse areas of their activity. The present analysis, performed among a group of 35 out of 129 museums recorded in the State Register of Museums in Poland, confirms this observation. The results show that the museums accept digitization as a crucial element of their activity. 69% of the institutions present some part of their collections online and 94% intend to increase the scope of digitization. However, most institutions share less than 25% of their current collections online despite having a larger part digitized. 83% of the museums share their collections exclusively on their own websites or dedicated platforms, and most institutions (62%) observe a positive connection between sharing collections online and the number of physical visits to the museum. Although still focused on collections rather than on audiences, as well as reluctant when it comes to sharing their resources in the widest and the most effective way, which has confirmed the conclusions from previous studies run in Poland and the EU (Enumerate, 2015; Konach, 2017; Misiak, 2017), these institutions eventually adopted digitization as not only inevitable, but above all, potentially beneficial. In fact, this technological innovation has appeared consonant with the original, multifaceted mission of the museum, making collections more accessible to visitors both offline and online, and the sightseeing process, along with the virtual one, more attractive.

With digitization and a wide variety of its applications, museums could achieve the Malreaux vision of the musée imaginaire, the museum without walls (Malraux, 1965; Lohman, 2010) in its contemporary definition, referring to the museum of the future (Griesser-Stermscheg et al., 2018). They could offer new experiences to new audiences, as well as new spaces to communicate and search for answers to the most urgent social and cultural questions of the present and the future, as well as be better prepared to operate in times of unexpected crises.

References

Andreacola, F. (2014). Musée et numérique, enjeux et mutations. Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication, 5. Retrieved from: https://journals.openedition.org/rfsic/1056 (17.07.2018), DOI: 10.4000/rfsic.1056

Bauman, Z. (2008). Płynna nowoczesność. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie.

Borowiecki, K. J., Navarrete, T. (2017). Digitization of heritage collections as indicator of innovation. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 26 (3): 227–246. DOI: 10.1080/

10438599.2016.1164488.

Borowiecki, K. J., Prieto-Rodriguez, J. (2015). Video games playing: A substitute for cultural consumptions? Journal of Cultural Economics, 39 (3): 239–258. DOI: 10.1007/s10824-014–9229-y.

Bosomtwe, O., Buchner, A., Janus, A., Wierzbicka, A., Wilkowski, M., Gryszko, E., Majdecka, E. (2018). Dobro wspólne. Pasja i praktyka. Retrieved from: https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/czytelnia/dobro-wspolne-pasja-i-praktyka/ (17.7.2018).

Brinkerink, M. (2015). Dutch cultural heritage reaches millions every month. Research & Development Blog, 17 June 2015. Retrieved from http://www.beeldengeluid.nl/en/blogs/research-amp-development-en/201506/dutch-cultural-heritage-reaches-millions-every-month (17.7.2018).

Citton, Y. (2014). Pour une écologie de l’attention. Paris: Le Seuil.

Citton, Y., Crary, J. (2014). L’économie de l’attention: nouvel horizon du capitalisme? Paris: La Découverte.

Commission Recommendation of 27.10.2011 on the Digitisation and Online Accessibility of Cultural Material and Digital Preservation (2011). Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:283:0039:0045: EN:PDF (5.9.2020).

Cultural Heritage. Digitisation, Online Accessibility and Digital Preservation. Report on the Implementation of Commission Recommendation 2011/711/EU (2016). Brussels: European Commission.

Digitalizacja dóbr kultury w Polsce (2014). Warszawa: NIK. Retrieved from: https://www.nik.gov.pl/plik/id,10408, vp,12737.pdf (5.9.2020).

Digitalizacja w muzeach. Retrieved from: http://digitalizacja.nimoz.pl/digitalizacja/digitalizacja-w-muzeach (17.7.2018).

Digitisation of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved from: http://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/digitisation-of-cultural-heritage (3.4.2019).

Enumerate (2015). Core Survey 3. Retrieved from: http://enumeratedataplatform.digibis.com/enumerate-survey-2015-excel-format/detail (3.4.2019).

Filiciak, M., Hofmokl, J., Tarkowski, A. (2012). The Circulations of Culture: On Social Distribution of Content. Retrieved from: https://obiegikultury.centrumcyfrowe.pl/the_circulations_of_culture_report.pdf (5.9.2020).

Góral, A. (2012). E-dziedzictwo–potencjał cyfryzacji w zakresie zachowania ciągłości przekazu niematerialnego dziedzictwa kulturowego. Zarządzanie w Kulturze, 13 (1): 87–100. DOI:10.4467/

20843976ZK.12.011.0625.

Greffe, X., Krebs, A., Pflieger, S. (2017). The future of the museum in the twenty-first century: recent clues from France. Museum Manage. Curatorship Museum Management and Curatorship, 32 (4): 319–334. DOI: 10.1080/09647775.2017.1313126.

Griesser-Stermscheg, M., Haupt-Stummer, C., Höllwart, R., Jaschke, B., Sommer, M., Sternfeld, N., Ziaja, L. (2018). The Museum of the Future. In: G. Bast, E. Carayannis, D. Campbell (Eds.), The Future of Museums: Art, Research, Innovation and Society. Springer, Cham: 117–128. DOI:10.1007/978–3–319–93955-1_11.

Guccio, C., Martorana, M. F., Mazza, I., Rizzo, I. (2016). Technology and Public Access to Cultural Heritage: the Italian Experience on ICT for Public Historical Archives. In: K. J. Borowiecki, N. Forbes, A. Fresa (Eds.), Cultural Heritage in a Changing World. Online: Springer Open, 55–76. DOI: 10.1007/978–3-319-29544–2.

Ilczuk, D. (2002). Polityka kulturalna w społeczeństwie obywatelskim. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

Janowska, A. A. (2017). Przemysły kultury w erze dostępu. Studia i Prace Kolegium Zarządzania i Finansów, 158: 179–199.

Kabassi, K. (2017). Evaluating websites of museums: State of the art. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 24: 184–196, DOI: 10.1016/j.culher.2016.10.016.

Konach, T. (2017). Koncepcje nowej muzeologii w kontekście zarzadzania kulturą niematerialną i własnością intelektualną w instytucjach kultury. Zarządzanie w Kulturze, 18 (2): 173–194. DOI: 10.4467/20843976ZK.17.011.7103.

Kultura cyfrowa (2017). Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego. Retrieved from: http://www.mkidn.gov.pl/pages/strona-glowna/finansowanie-i-mecenat/programy-ministra/programy-mkidn-2017/kultura-cyfrowa.php (17.7.2018).

Liebowitz, S. J. (2013). Internet piracy: The estimated impact on sales. In: R. Towse, C. Handke (Eds.), Handbook of the Digital Creative Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 262–273.

Liebowitz, S. J. (2014). The impacts of internet piracy. In: R. Watt (Ed.), The Economics of Copyright. Edward Elgar, 225–240.

Liebowitz, S. J. (2017). Responding to Oberholzer-Gee & Strumpf’s Attempted Defense of Their Piracy Paper. Econ Journal Watch, 14 (2): 174–195. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2887122.

Lohman, J. (2010). Muzeum otwarte. Dla kogo? Oto jest pytanie. In: Muzeum przestrzeń otwarta? Wystąpienia uczestników szóstego sympozjum problemowego Kongresu Kultury Polskiej, 23–25.9.2009, Rottermund A. (Mod.), Warszawa.

Malik, R. (2018). Key location factors and the evolution of motives for business service offshoring to Poland. Journal of Economics & Management, 31: 119–132. DOI: 10.22367/jem.2018.31.06.

Malik, R., Janowska, A. A. (2018). Megatrends and Their Use in Economic Analyses of Contemporary Challenges in The World Economy. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, (523): 210–221. DOI:10.15611/pn.2018.523.18.

Malik, R., Janowska, A. A. (2019). The next 100 years–applying megatrends to analyze the future of the Polish economy. Nierówności Społeczne a Wzrost Gospodarczy, 1 (57): 119–131. DOI: 10.15584/nsawg.2019.1.8.

Malraux, A. (1965). Le Musée Imaginaire. Paris: Gallimard.

Misiak, J. (2017). Bariery w zarządzaniu muzeami. Raport z badań. Poznań: Fundacja ARTnova.

Museum of the Future: Insight and Reflections from 10 international museums (2019). In: D. Sturabotti, R. Surace (Eds.), EU: Mu. SA: Museum Sector Alliance. Retrieved from: http://www.project-musa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/MuSA-Museum-of-the-future.pdf (5.9.2020).

Navarrete, T. (2013a). Digital Cultural Heritage. In: I. Rizzo & A. Mignosa (Eds.), Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 251–271.

Navarrete, T. (2013b). Museums. In: R. Towse, C. Handke (Eds.), Handbook of the Digital Creative Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 330–343.

Navarrete, T., Borowiecki, K. J. (2016). Changes in cultural consumption: ethnographic collections in Wikipedia. Cultural Trends, 25 (4): 233–248. DOI: 10.1080/09548963.2016.1241342.

O projekcie (2013). NIMOZ. Retrieved from: http://digitalizacja.nimoz.pl/programy/e-muzea/o-projekcie (17.7.2018).

Paolini, P., Mitroff Silvers, D., Proctor, N. (2013). Technologies for Cultural Heritage. In: I. Rizzo, A. Mignosa (Eds.), Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 272–289.

Parry, R. (2013). Museums in a digital age. London: Routledge.

Pasikowska-Schnass, M. (2018). Cultural Heritage in EU Policies. European Parliament. Retrieved from: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/621876/EPRS_BRI (2018) 621876_EN.pdf (5.9.2020).

Poole, N. (2010). The Cost of Digitising Europe’s Cultural Heritage. A Report for the Comité des Sages of the European Commission. Brussels: Common Trust. Retrieved from http://nickpoole.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/digiti_report.pdf (5.9.2020).

Potts, J. (2014). New Technologies and Cultural Consumption. In: I. Ginsburgh, D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 215–232.

Schmitt, D., Meyer-Chemenska, M. (2015). 20 ans de numérique dans les musées: entre monstration et effacement. La Lettre de l’OCIM. Musées, Patrimoine et Culture scientifiques et techniques, 162: 53–57. DOI: 10.4000/ocim.1605.

Towse, R. (2010). A textbook of Cultural Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wallach, R. (2001). Features – Does Cultural Heritage Information Want To Be Free? A Discourse on Access. Art documentation: bulletin of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 20 (2): 42. DOI: 10.1086/adx.20.2.27949152.

Zawojski, P. (2005). Muzea bez ścian w dobie rewolucji cyfrowej. In: M. Popczyk (Ed.), Muzeum sztuki: antologia, Kraków: Universitas, 685–696.