2(26)2020

Delali A. Dovie1

Articulation of the shallow inclusion

and deep exclusion of older adults

from the Ghanaian policy terrain

Abstract

The paper examines how the Ghanaian policy environment shapes access inequalities in well-being at old age, utilizing qualitative and quantitative datasets obtained from individuals aged 50+ (n = 230). The results show from older people (70%) that aged policy extensively excludes older adults. This denotes an incomprehensible policy domain that comprises the constitution, social protection policy, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) act, and the national ageing policy. The challenge is the mandatory retirement age is 60 years; while the compartmentalization of the NHIS free healthcare provision is for those aged 70+, the Welfare Card (EBAN) provides access to social amenities, including transportation, to older people 65+ at a discount of 50%. However, older adults are not a homogenous group. These policies address needs of the aged incoherently, with currency across the spheres of social exclusion and inclusion. However, a policy is a key resource, the limitation of which may have dire repercussions, including ageism. This has broader implications for social, economic, political exclusion regarding multi-dimensional facets of healthcare and labor force participation. These are discussed in light of the three pillars of ageing social policy, namely healthcare, paid work, and social care. The paper argues that government policy is skewed towards children, youth, gender, and education, despite older adults’ increasing population, without an appreciation for concrete and determinate policies.

Keywords: older adults, policy, eligibility, social exclusion, social inclusion, active ageing, coping strategies

JEL Classification Codes: I38, J14, J18, N37

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2020.2.3

Artykułowanie płytkiego włączenia i głębokiego wykluczenia osób starszych z obszaru politycznego w Ghanie

Streszczenie

Artykuł analizuje, w jaki sposób środowisko polityczne Ghany wpływa na nierówności w dostępie do dobrobytu osób w starszym wieku. Badanie opiera się na wykorzystaniu jakościowych i ilościowych zbiorów danych uzyskanych od osób w wieku 50+ (n = 230). Wyniki badań z udziałem osób starszych pokazują (70%), że polityka wobec starzenia się w znacznym stopniu wyklucza te osoby. Oznacza to niezrozumiałą dziedzinę polityki obejmującą konstytucję, politykę ochrony socjalnej, Ustawę o krajowej ankiecie dotyczącej wywiadu zdrowotnego (ang. National Health Interview Survey – NHIS) oraz krajową politykę dotyczącą starzenia się ludności. Wyzwanie polega na tym, że obowiązkowy wiek emerytalny wynosi 60 lat, podczas gdy zaszeregowanie bezpłatnej opieki zdrowotnej przez NHIS dotyczy osób w wieku 70+, a karta opieki społecznej (EBAN) zapewnia dostęp do udogodnień socjalnych, w tym transportu dla osób starszych w wieku 65+ ze zniżką 50%. Jednak starsi dorośli nie stanowią jednorodnej grupy. Polityka ta uwzględnia potrzeby osób starszych w sposób niespójny, przy czym obejmuje obszary wykluczenia społecznego i integracji. Polityka jest jednak kluczowym zasobem, którego ograniczenie może mieć poważne konsekwencje, w tym wzmacnianie dyskryminacji ze względu na wiek. Ma to szersze implikacje dla wykluczenia społecznego, gospodarczego i politycznego w odniesieniu do wielowymiarowych aspektów opieki zdrowotnej i uczestnictwa w zasobach siły roboczej. Są one omawiane w świetle trzech filarów polityki społecznej wobec starzenia się, a mianowicie opieki zdrowotnej, pracy zarobkowej i opieki społecznej. Artykuł stawia tezę, że polityka rządu jest ukierunkowana na dzieci i młodzież oraz jest wypaczona pod względem płci i wykształcenia, pomimo rosnącej populacji osób starszych, bez docenienia konkretnych i wybranych dziedzin polityki.

Słowa kluczowe: starsi dorośli, polityka, kwalifikowalność, wykluczenie społeczne, włączenie społeczne, aktywne starzenie się, strategie zaradcze

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: I38, J14, J18, N37

Population ageing is a worldwide occurrence, posing severe challenges for the traditional social welfare state (Christensen et al., 2010). It has been observed that a reasonable strategy to cope with the economic implications of population ageing is to raise the typical age of retirement, and most governments are moving in this direction, particularly in the developed world. In other contexts, policy dimensions are proffered in terms of improvements in health and functioning along with the shifting of employment from jobs that need strength to jobs needing knowledge, implying that a rising proportion of people aged 60+ are capable of contributing to the economy. This is because many people in this age category would prefer part-time work to full-time labor. This depicts an increase in jobs that need 15, 20, or 25 hours of work per week.

The remainder of the paper is ordered as follows: section two consists of a literature review and theoretical framework, section three discusses methods employed in the study, section four presents study results, section five is the discussion, and section six summarizes the paper.

Literature review

The plight of older adults

Older adults’ population is increasing in the midst of the breakdown of family structures and rising healthcare costs (Dovie, 2018a; Parmar et al., 2018). Yet, most African countries have no social health protection for older adults (Parmar et al., 2018). Efforts to prevent discrimination, for example in employment and health settings, may serve as systemic measures to promote a more inclusive society (Gooding, Anderson, NcVilly, 2017). Two distinct exceptions include Senegal’s Plan Sesame, a user fees exemption for older people, and Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), where older people are exempted from paying premiums. Evidence on whether older adults are aware of and enrolling in these schemes is lacking, though. Walsh, Scharf, and Keating (2017) identify services as the sixth domain shaping old-age exclusion, next to social, economic, and civic exclusion, ageism, and neighborhood. States, societies, and communities play roles in old-age exclusion (Walsh et al., 2014). Parmar et al. (2018) found that older adults are vulnerable to social exclusion in all the social, political, economic, and cultural dimensions. The literature review revealed a surprisingly small amount of formal literature about creating social inclusion in policy and practice for people with disabilities (nine in total), and most of it concerned people with intellectual and cognitive disabilities (Gooding et al., 2017).

Notions of social inclusion and social exclusion in social care

Social inclusion emerged in France in the 1970s as a social policy to assist marginalized citizens (Silver, 1994), including older adults. The concept has since been diffused through social policy worldwide. However, several factors serve as barriers to social inclusion, namely religion (Wilde, 2018), policy, and limited resources (Zaidi, 2012). Socially, exclusion is used as a synonym for poverty, marginalization, detachment, unemployment, or solitude.

Social exclusion provides a useful way to understand poverty and disadvantage in a way (Wilde, 2018), including income, assets, access to health services and transport. The exclusion of older adults is partly caused by negative attitudes and discrimination (Azpitarte, 2013; Gooding et al., 2017). Economic exclusion of older individuals, for instance, through insufficient pension benefits (e.g., Peeters, De Tavernier, 2015), may lead to both social and political exclusion. These directly or indirectly promote social inclusion.

Active ageing refers to older people being full citizens of society (Walker, 2002). Yet, full citizenship is attained when individuals actively participate in social and political life and have a feeling of belonging to the society on equal footing with others. A number of structural barriers to the full participation of older individuals in society pertain. For instance, limited resources can act as a barrier (Zaidi, 2012). Thus, having certain rights is not sufficient in itself, since there is a need for a certain amount of resources to exercise one’s rights. It is worth stating that such resources could find expression in the policy environment. Ageist ideas are still widespread in European societies (Ayalon, Tesch-Römer, 2017; 2018), leading to the exclusion of older adults from several domains of life, including, but not limited to, the labor market. However, the rates of social and economic inequality facing Australians with disabilities compared to their fellow citizens are among the highest in the world (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2011).

Since the government is not forthcoming with a consolidated aged care regime for older people, informal care needs to be invigorated to attain the same aim. Stated differently, based on current situational analysis, informal care may be better for meeting the life-sustaining needs of older adults in Ghana. However, with time a new model of care called “mixed care” may have to be created, combining formal and informal (familial) care for older people (Dovie, Ohemeng, 2019).

Social care dynamics for the Ghanaian elderly

The 2010 Population and Housing Census shows that although the proportion of older persons (60+ years) decreased from 7.2% in 2000 to 6.7% in 2010, in terms of absolute numbers there has been a sevenfold increase in the population of older persons from 215, 258 in 1960 to 1, 643, 978 in 2010 (National Population Council (NPC), 2014). The growing population of older people comes with an increase in degenerative and non-communicable diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, cancers, cardiac-related diseases, including dementia. The Ghana Health Service (GHS) lists hypertension, skin diseases, diarrhea, acute eye and ear infections, rheumatic and joint diseases among the top 20 diseases affecting Ghanaians (GHS, 2010).

Health promotion entails improved diet and/or increased exercise, which may reduce the onset of illness and hence life expectancy (Dovie, 2018b). However, the NHIS scheme does not cover all illnesses, including surgical operations and hospital admission costs (Dovie, 2019a, Soussey, 2015). The challenge for the older population in Ghana is that the retirement age for public sector workers is 60 years; while the NHIS provides free care to those aged 70+ years (NHIS, 2003). Dovie (2019b) expands older people’s social needs, especially in the healthcare dimension, to encompass geriatric care needs.

Older adult-oriented policy environment

The Ghanaian policy domain is largely interspersed with policies on children (e.g., Children’s Act (Act 566); PNDC L111, United Nation’s (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child); the youth (e.g., National Youth Policy; Youth in Afforestation program; NABSCO); gender (e.g., Legal Aid Scheme, Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), and the Domestic Violence Act, National Gender Policy, the 1992 constitutional provision, Sustainable Development Goals, Universal Declaration of Rights); women (e.g., the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women and the Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. The Beijing Platform for Action in 1996 and the Charter on Human and People’s Rights, and the Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa), health (e.g., national health insurance scheme); maternal health (e.g., Free maternal and child healthcare programs); education (e.g., Education for All; Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE); Free Secondary High School (SHS) policy; Double track education policy; Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET); The school feeding program and take-home rations for girls, Free school uniforms program); employment and pensions (e.g., the International Labour Organization’s Convention on workers and the National Pension’s Act, 766); development (e.g., Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda); social protection (e.g., social protection policy); ageing (e.g., the African Union’s policy framework and Action plan on ageing; the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing; the national ageing policy); the rights to information (RTI) and a host of others to the detriment of robust older care policies.

Out of these, the old age-related policies encompass those that only contain aspects of older adult issues, namely the 1992 Constitution, Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA), 2010–2013), the National Pension’s Act, 766, social protection policy and the African Union’s policy framework and Action plan on ageing; the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. Full-fledged policy on ageing entails the national ageing policy.

The 1992 Constitution’s Article 37 (2) (b) states that the State shall enact appropriate laws to assure the protection and promotion of all other basic human rights and freedoms, and the rights of the disabled, the elderly, children and other vulnerable groups in the development process. Article 37 (6) (b) of the same Constitution also adds that the State shall provide social assistance to older people to enable them to maintain a decent standard of living (Government of Ghana (GOG), 1992).

The NPC, Revised Edition, 1994 also recognized older people as an important segment of the population of Ghana and outlines actions to promote their full integration into all aspects of national life through advocacy, enactment of laws and collaboration between all stakeholders – government, family and community, the private sector, employers and organized labor, older people’s groups and associations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations (CSOs) and development partners in dealing with older adults (NPC, 1994).

The NHIS Act (Act 650) of 2003 also makes provision for an exemption for individuals aged 70+ years and non-contributors to the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT). Additionally, the exemption clause covers older adults aged 65+ and registered under the LEAP Cash Transfer Program from the payment of registration fees and premiums to access health services under the NHIS (Dovie, 2019a).

The National Pensions Act, 2008, is another policy that concerns the older person. One of its functions is to ensure the mobilization of funds through pension contributions by the working population for various contingencies, particularly old age, invalidity, and death (GOG, 2008).

The National Ageing Policy (NAP) (2010) of Ghana has for its theme “Ageing with Dignity,” which suggests that ageing should be characterized by the elderly having full knowledge of their roles and playing them to attain full social dignity. This policy document discusses the strengthening of social protection schemes for older persons, particularly the long-term care of the poor and frail (mostly women). Further, it argues for the promotion of life-long education training, healthy and active ageing. Life-long education and training mentioned here may have implications for generational digital literacy. Thus, Dovie et al. (2020) underscore the significance of generational digital literacy, which is facilitated by digital literacy, yet older people are largely deficient in. Such digital literacy deficiency among older adults may be resolved through the phenomenon of intergenerational socialization, particularly that induced by younger persons. Older adults have entitlements to full access to healthcare and services, including preventive, curative, and rehabilitative care (GOG, 2010). It also seeks to protect the rights of the older persons; reduce poverty among older people; improve income security and enhance social welfare for older adults; ensure adequate attention to gender variations in ageing; strengthen research, information gathering and processing, and coordination and management of data on older persons; strengthen the capacity to formulate, implement, monitor and evaluate policies on ageing, among others.

Although the NAP was developed in 2010, it has not been implemented because it lacks a legal backing instrument. However, if older people are referred to as vulnerable people, it denotes the expedition of action to alleviate their plights. Yet, this is not in sync with the emphasis on the sustainability of policy implementation. It also lacks the requisite national ageing council to ensure its implementation.

The Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA), 2010–2013 articulates the strategies for addressing the concerns of older adults which include developing a national policy on ageing (Appiah-Kyei, 2013). The social protection policy attempts to deliver a well-coordinated and inter-sectoral social protection system that will enable people to live their life in dignity. This will be attained through social assistance to reduce poverty, promote productive inclusion income support, livelihood empowerment and improved access to basic access schemes (e.g., Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty (LEAP), EBAN card (Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (MGCSP), 2015) among others. The inclusivity mandate in the context of this policy has been compromised, premised on the fact that the retirement age is 60 years, yet beneficiaries of LEAP and EBAN card are to be aged 65+. This depicts a node of exclusion.

Collectively, these have made some provisions for older adults, yet not concretely and coherently, creating the impression of older adults’ inclusivity. Also, they provide older adults’ needs incoherently, an indication of marginalization of older adults and, therefore, a deep exclusion of them. Further, policies and documents on ageing at all levels provide incentives and strategies for active ageing.

The dimensions of social care inclusion for Ghanaian older adults involve healthcare, social care, and paid work. More so, family care systems have weakened over the last few decades and the care and support that in the past was provided to older family members is no longer given (Aboderin, 2006; Apt, 1996; van der Geest, 2007; Doh, Afranie, Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, 2014). The breakdown in family and community structures and the rising costs of living and healthcare deepened the vulnerabilities experienced (Apt, 1996; Doh et al., 2014; Palmer et al., 2014) by older Ghanaians. Further, ageist ideas are still widespread (Ayalon and Tesch-Römer, 2017; 2018) worldwide, leading to the exclusion of older adults from several domains of life, including healthcare, the labor market, and social care. This situation implies vulnerability to economic dependence in later life (De-Graft Aikins et al., 2016) in an era of longevity and inadequate formal support infrastructure (Aboderin, 2006; Dovie 2018a; 2018b).

Just as religious inequality has not been a commonly acknowledged nor researched phenomenon (Wilde, Tevington, Shen, 2018), so is social inclusion and exclusion in Ghana. The World Health Organization’s (WHO, 2002) active ageing framework recognizes that age barriers and ageism need to be removed in order to increase the potential for active ageing. However, there has been little empirical analysis of ways in which ageism and attitudes toward age impact active ageing through the conduit of social inclusion and social exclusion among older adults and the associated coping strategies. Furthermore, few studies exist on welfare programs for the Ghanaian elderly (e.g., Aboderin, 2006; van der Geest, 3016; Kpessa-Whyte, 2018). There is a gap in knowledge in terms of social inclusion and social exclusion of older adults in ageing social policy in Ghana. It is this gap that this study sought to fill by focusing on the healthcare, paid work, and social care pillars of ageing social care in the Ghanaian policy domain, how these shape inequalities in health and well-being.

Hence, this study sought to investigate the extent to which the Ghanaian policy environment includes and excludes older people in terms of welfare provisions. The objectives of the study are as follows: first to ascertain the extent to which Ghanaian older people are socially included in and excluded from formal support infrastructure (FSI), and second, to elucidate the coping strategies older individuals employ in order to counteract exclusion in state welfare provisions – healthcare access, paid work beyond retirement, social care – institutional care.

Theoretical framework

The systems-theoretical framework developed by Niklas Luhmann provides the tools to understand inclusion and exclusion in a theoretically adequate way. By and large, the Luhmannian theory follows the sociological tradition of differentiation, according to which society is not understood as a single unit (such as a collective of people) but in terms of difference. The justification for directly translating this theory into the sphere of the public policy lies in the fact that functional analysis provides the admissible pattern for the rationalization for decision-making, especially that which is aged-oriented. Further, Luhmann’s systems theory has been applied globally, and in different scientific disciplines, namely sociology, political science, jurisprudence (i.e., sociology of law), family therapy, educational science, literature, communication, research (especially journalism research) and can thus be characterized as social systems of aged care inclusion and exclusion self-organization. In addition, in modern societies, societal spheres have separated and have fulfilled different and exclusive functions for society: politics provides overall decisions for society, economy distributes goods and services; science provides knowledge, whereas law provides justice within society.

The Luhmannian systems theory demonstrated that the contemporary society is no longer primarily structured by social stratification or geographical differences. From Luhmann’s perspective, the core characteristic of society is differentiation into a number of communication systems such as the economy, politics, law, science, religion, medicine, education, and social help (including social care for the elderly). What these systems have in common is that they fulfil a function for society, i.e., they solve a specific reference problem for society. Politics, for instance, solves the problem of order by providing collectively binding decisions (Luhmann, 2000a), for instance on ageing social policy; the economy deals with the allocation of resources under conditions of scarcity (Luhmann, 1988a); science helps to advance knowledge (Luhmann, 1990).

On the basis of their functional primacy, the function systems achieve operative closure (Luhmann, 1997: 748). Operational closure means that the systems structure their communications based on their unique observation code (also known as guiding difference). The communication system of states or governments is expected to enact laws and policies and facilitate their implementation, efficiency, and effectiveness in addressing the social inclusion and exclusion needs of the elderly. Due to its specialization, each system is hypersensitive to specific events that its unique guiding difference allows it to see; it is blind and, therefore, indifferent to everything else. The function system codes reduce the enormous complexity of the world to a small window of relevance.

The organization is a type of social system which reproduces itself through a recursive network of decisions and which discriminates between members and non-members (Luhmann, 2000b). Thus, the ageing social policy decisions in Ghana discriminate against older adults, In contrast to function systems, organizations have two special features: they can have a hierarchical structure and build up complex arrangements of expectations regarding behaviors, which is true in terms of governments; and they have a communicative address (Luhmann, 1997: 834f), which enables them to communicate with other organizations. Organizations normally operate within the context of function systems. For example, banks and businesses can be considered as organizations in the context of the economy; schools in the context of education; churches in the context of religion; hospitals in the context of medicine; research institutes and universities in the context of science; parties, governments and non-governmental organizations in the context of politics; among others. However, it is essential to note that organizations follow their own internal routines (such as decision procedures, membership rules, micropolitical rationalities) affecting different social groups: vulnerable groups like the elderly in the process. The horizon of the political system contains only political distinctions and, therefore, provides political criteria. However, an organization (or individual) can shift from one perspective to another.

Methods

The study used quantitative and qualitative datasets and a cross-sectional design to investigate the healthcare, paid work, and social care pillars of ageing social policy and how these shape inequalities in health and well-being. Use was made of a questionnaire, which provided the basic data for the development of an understanding of the repertoire of Ghana’s policy domain, including qualitative interview data obtained from near olds and retirees. The study population was constituted by individuals aged 50+ years, males and females, who live in Accra and Tema. Ghana was chosen as the study site because it reflects a context in which the extended family support system was practiced up until the decline of the same in recent times. This is due to urbanization, modernization, and globalization, including the increasing spate of individualization. Accra and Tema are typical of major Africa cities that are privy to extended family support systems and associated issues, hence their selection. They were also chosen because they depict the epitome of urban settings.

The study adopted the simple random sampling technique in selecting the respondents. For the quantitative data, 230 workers in the near old age category and retirees were selected. In the case of the qualitative data, 16 in-depth interviews were conducted with a section of individuals with the requisite information, including 2 key informants. In this research, the inclusive criteria comprised individuals in the following age categories: 50–59 and 60+; male or female; who were working; belonging to the Ghana National Pensioners’ Association; including the willingness to give informed consent. The exclusion criteria entailed individuals aged less than 50+ years; as well as unwillingness to give informed consent.

Thus, the sampling process entailed the random sampling of working individuals aged 50–59 years (50) in the Tema Metropolis based on a list obtained from Tema Development Corporation’s Human Resource personnel. People aged 60+ years (180) were selected using a list obtained from the Pensioners’ Associations in Accra (90) and Tema (90). The samples were selected from a total population of 364 and 700+, respectively. Therefore, 250 questionnaires were given out, and 230 were returned. Although the sample size was constrained by resources, 230 observations were selected as adequate for the study. The proportion of individuals in the present sample reflects those of the population aged 50+ in Accra and Tema. The sample is large enough to help address the research objectives accurately.

The administration of the questionnaire took the form of face-to-face interviews, including self-administration. The face-to-face interviews were conducted in both English language and local Ghanaian languages, namely Ga, Ewe, and Twi.

The answered questionnaire was cleaned and serialized for easy identification. The survey data were entered into Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) and were analyzed with selected descriptive statistics, namely frequencies, percentages, Chi-square statistics, and Cramer’s V test. Each in-depth interview was conducted individually in the participant’s office or chosen place. The interviews were audio-taped. The interview data were coded with NVivo software and conducted along with the following procedures: first, there was the creation of a list of coding cues, and second, analysis of verbatim quotes of the narratives from participants thematically. Data were analyzed thematically.

Ethical consideration, validity, internal consistency, and reliability

The University of Ghana’s Institutional Review Board approved the project. During the data collection process, written informed consent was obtained from each individual research respondent during the process of data collection. Permission was also sought from the respondents to record the interview.

The questionnaire and interview guide were piloted to ensure accuracy in understanding, fluency, and proper wording of questions, including initial validation. The validity of the survey data was attained following Nardi’s (2006) guidelines. That is, the validity of the data was obtained from face-to-face interviews. Also, trait sources of error were minimized through interviewing respondents at their convenience. To achieve this, multiple interview appointments were scheduled.

Presentation of findings

Participants’ socio-demographic characteristics

The study population consisted of males (47.3%) and females (52.8%) aged between 50+ years (Table 1). The respondents (58%) were married. Most of the respondents had some level of education. On the whole, the highest educational level attained by the majority of the respondents (80.3%) was tertiary education. The discussion above shows that the sample is composed of high proportions of university graduates, some of whom are engaged in paid work (51.3%).

Table 1. Socio-Demographics

|

Variables |

Characteristics |

Percentages (%) |

|

Age Sex Education Marital status Occupation |

50–59 60–69 70–79 80–89 90+ Males Females No-formal Pre-tertiary Tertiary Married Divorced Widowed Single Working Not working |

23.9 23.9 23.9 23.9 4.3 47.3 62.8 9.2 17.5 80.3 58.0 23.5 7.5 11.0 51.3 48.7 |

Source: field data.

Quantitative results

Awareness of Ghana’s policy provisions for older people

Older adults’ awareness of policy provisions for them facilitates knowledge of its existence, followed by the elicitation of the right to benefit from these appropriately. The range of such provisions presently in Ghana encompasses LEAP, NHIS, EBAN card, property rebate, and including pensioners’ medical scheme (PMS). Of all these, the older adults were aware of the NHIS to a greater extent (100%), with the least being the property rebate provision (40.1%), (Table 2).

Table 2. Notion of resource awareness

|

Resources |

Yes |

No |

Total |

|

EBAN card LEAP NHIS PMS Property rebate |

78.3 94.5 100.0 64.8 40.1 |

21.7 5.5 0.0 35.2 59.9 |

100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 |

Source: field data.

The extent of awareness is reminiscent of the level of utilization with the exception of the near old respondents.

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis of welfare policy provisions for older Ghanaians

Strengths

The interview data shows that the strengths dimension of this analysis intimates that some policy provisions exist with older persons’ care sensitivity, as enshrined in the 1992 Constitution; National ageing policy; social protection policy including their respective welfare-related provisions, namely NHIS; LEAP; EBAN Card; and property rebate.

Weaknesses

Further, the weaknesses aspect elucidates the fact that policy provisions have ageist connotations when juxtaposed with the mandatory retirement age (60 years). It is also reminiscent of ineffective implementation and adherence to the paid work dimension of the national ageing policy and non-contributory pensions’ sentiments.

The qualitative data shows in terms of the welfare facilities for older adults in Ghana that LEAP, which is for non-pensioners, its eligibility age for benefiting is 65+. The NHIS provides free care for people aged 70+ entailing LEAP beneficiaries. The EBAN Elderly Welfare Card provides transport services at a 50% discount accessible to people aged 65+ years old. Last but not least, a 30% property rebate pertains to people aged 60+. Hence, with the exception of the property rebate item, which fosters inclusivity in terms of the needs of the elderly at 60 years, all the others have 65+ as the age benchmark. These are discriminatory in terms of age. As a result, such have necessitated the resort to the search for and patronage of a contingency of social inclusion coping strategies, mentioned below. The latter unequivocally suggests that older persons are organizing themselves within the vacuum herein created by policy. This is particularly essential as kin support becomes more attenuated and fragile, including the inability of the Ghanaian health system to accommodate the needs of ageing adults.

The data were subjected to Pearson Chi-square statistics and Cramer’s V test to examine any association between the extent of awareness of facilities and age. The results showed Cramer’s V = 0.342, which suggests a positive but weak association between the two variables (Table 3).

Table 3. Statistical tests of association existing between policy intervention facilities

and age

|

Statistical tools |

Value |

Degree of freedom |

Asymp. Sig. (2-sided)/approx. sig |

|

Pearson Chi-Square Cramer’s V N of Valid Cases |

15.956 .342 442.00 |

18 |

.000 .000 |

Source: field data.

Opportunities

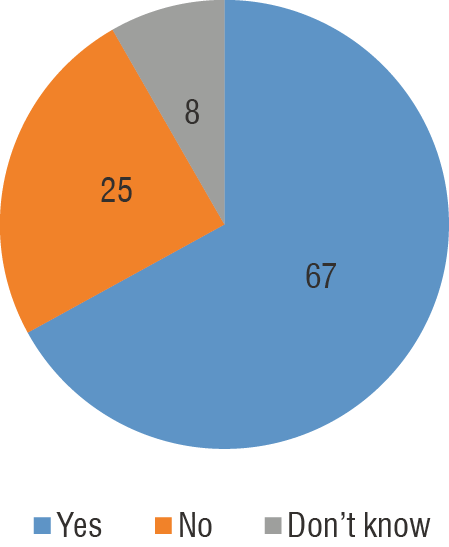

There were divergent views on the need for the ratification of the Convention on the Rights of Older People (CROP) in Ghana. Hence, the results show that there is a need for legislation on older people in the form of the CROP from the majority of respondents (67%) (See Figure 1 below). The CROP’s ratification offers opportunities at two levels, namely: the state level to enact the CROP, thereby offering protection to beneficiaries. In the same vein, individual older adults may benefit from the CROP, since it has the propensity to provide protection to them in a myriad of ways entailing protection against unfair treatments and witchcraft accusations and associated violence.

Figure 1. The Convention on the Rights of Older People (CROP) as a measure to meet the life-sustaining and protection needs of older people (in %)

Source: field data.

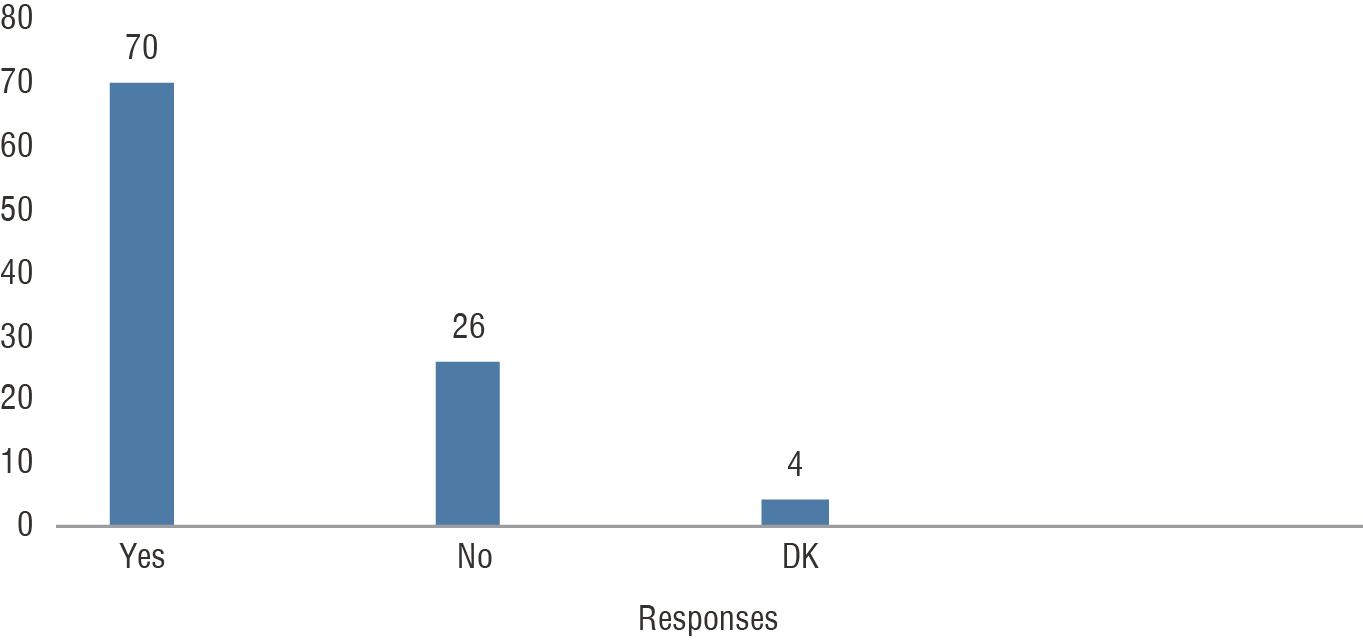

The older adults opined that inasmuch as the ratification of the CROP is imperative, so should the Ghanaian society be sensitized about the fact that older people can still be productive in the society. In furtherance, to the proceeding fact, the study has observed that from the respondents (70%) that aged policy extensively excludes older adults (See Figure 2 for details).

Figure 2. Extent of exclusion (in %)

Source: field data.

Social exclusion from benefiting from policy provisions is an impending threat to the well-being of the elderly. This is problematic because the increasing population requires the reverse, i.e., social inclusion as ageing is inevitable.

Qualitative results: Social inclusion facilitating coping strategies

Another individual level opportunity relates to the pursuance of social inclusion, facilitating coping strategies. These coping strategies serve as opportunities employed as a way of salvaging the situation of vulnerability to social inclusion. These social-inclusion facilitating coping strategies are discussed along the trajectory of healthcare, paid work, and social care. First, from the viewpoint of healthcare, a variety of strategies were adopted by older adults by way of supplementing the NHIS’s woefully inadequate provisions made by the State, with its associated exemption clause. For instance, the PMS instituted and implemented, provides healthcare to people aged 60+, including the non-exempt category as well as the exempted. The following quotes are illustrative of this fact:

We realized that our pension incomes are inadequate to cater for our health needs, see, so we have come together to establish the PMS (Key Informant Interviewee 2).

In furtherance to that, the act of exercising (e.g., the Ceragym concept) as a healthcare dimension was resorted to as exemplified by the statement below.

I visited the facility for a few months, and I have seen a drastic improvement in the health conditions for which I resorted to this regime (Male, Retiree).

I have problems with memory loss or forgetfulness of virtually everything, including my children, it was for this reason that I joined the ceragym contingent. Anyway, I am just trying my luck (Male Retiree).

The ceragym system can be found nationwide, including locations such as Tema, Spintex Road, Haatso, among others. Further, the preceding statement is reflective of memory loss associated with old age, and, therefore, dementia. It is an indication that dementia is increasingly becoming a social and health concern to older folks in Ghana and, therefore, must be tackled.

Second, the paid work beyond pension’s component of older people’s coping strategies brings to the fore three unique pathways. The formal to formal trajectory depicts a context in which older adults move from working in formal sector organizations to another in the same sector during the retirement transition. The following voices clearly articulate this fact.

I work at the Pensioners’ office at Osu. I once worked at the Ministry of Youth and Sports. We are given something small for our labor (Male Retiree).

I am a social worker on retirement, but I was taken on to work at the courts for a couple of days at the courts – Tuesdays and Wednesdays. I am given what I call windfall at the end of the month (Female Retiree).

I once worked as a military officer with the Ghana Armed Forces, but I retired years ago and had a contract here as the Head of Security (Male Retiree).

I am a social worker who retired recently. I was taken on to work at the Tema High Court. We go to court on Wednesdays every week. I am given a token at the end of the month (Female Retiree).

I once worked at the Ministry of Fisheries. However, when I retired, I came to occupy this chairman position at the Tema Community 2 Pensioners’ Association office. Our efforts are rewarded no matter how small (Male Retiree).

I am currently the chairman of the Ghana Veterans’ Association, where I report to work from Monday to Friday. I worked at the Ghana Ports and Harbor’s Authority before retiring (Male Retiree).

Third, there are individuals who worked in the formal public sector but diverted to the formal private sector for paid work. They explained that:

I was once a headmistress. This motivated me to establish a school to occupy me when I retire. This is exactly what you currently see (Female Retiree).

I just thought it was wise for me to undertake commercial farming as I have a vast landmass. It could become a legacy for my children someday. It is really paying off. If I had seen this much earlier, I would have been a millionaire before now, plus it occupies me (Male Retiree).

Finally, this particular pathway is characterized by individuals who once worked in the formal sector, who divert and get engaged in paid work after retirement in the informal sector. It comprises bankers, teachers, and other public servants.

I worked as a banker, but prior to my retirement, I decided to go into trading in toiletries, for which I bought a shop and started business thereafter (Female Retiree).

Long before I retired, when we were building our house, a store was attached to it that is what I use for my provisions shop after retiring from the teaching field. So at least, I could be at home and at the same time doing business (Female Retiree).

I thought I could occupy myself with this buy and sell the business of mine. It keeps me busy, although not as busy as I used to be at the Lands Commission (Female Retiree).

The significance of all these voices has been couched or summarized in the following quotation.

In terms of paid work beyond retirement, the way forward is engaging in paid work in the non-farm and farm, and trading sectors of the economy (Key Informant Interviewee 2). This has implications for paid work and an ageing social policy.

From the paid work dimension, it is observed that few retirees are engaged in the formal sector labor market due to the limited employment opportunities available therein. Improvements in health and functioning along with shifting of employment from jobs that need strength to jobs needing knowledge, imply that a rising proportion of people in their 60s and 70s are capable of contributing to the economy. Because many people aged 60+ would prefer part-time work to full-time labor.

Policy threats

Finally, policy provision (inadequacies) may be threatened by the increased older adults’ population. Further, the lack of a coherent policy environment for older people is yet another challenge, including increased life expectancy and weakened traditional family support systems. It is worth reiterating the fact that “advanced countries” family structure necessitated the establishment of more FSI. On the contrary, notwithstanding its decline, Ghana’s family support system still acts as a buffer against the pressure of the establishment of FSI” (Key informant interviewee 1). From the point of view of the CROP, it was observed that “there is an African protocol on the rights of older people, resulting in the lack of political will to sign onto the CROP. Besides, our governments are not keen on signing on to items that have no direct financial gains” (Key informant Interviewee 1), including political gains. This quote is suggestive of the fact that other policy choices militate against Ghana’s enactment of the CROP bid. Essentially, the Ghanaian policy terrain is, therefore, currently ageist in nature. Yet, ageism Walsh et al. (2017) admit it is one of the domains that shape old-age exclusion as earlier indicated. The interview data further reiterate the following “as if this is not enough, we older people are referred to by the youth and some pastors as witches and wizards, just because of differences in ageing experiences” (Female retiree).

The older adults who participated in the study are in no way homogenous in terms of the quantum of income and measures of income sufficiency and access to social needs. Heterogeneity in this context is at three distinct levels: 1) heterogeneity between formal and informal sectors; 2) heterogeneity among or within the formal sector, where there are end-of-service benefits (ESB) or occupational benefits such as medical bills, mortgage loans for the housing scheme, provident funds, funeral, marriage as well as related bills for workers; and 3) heterogeneity within informal sector workers – no pension contribution versus pension contribution. These have implications for diversity in coping strategy diversification. Thus, there is a systemic shift in sectoral choices regarding formal to informal sector employment during retirement, due mostly to the regimented strain of timing of work endured and a host of others. As logical as this may be, it is suggestive of the absence of designated employment opportunities for older Ghanaian adults. Ultimately, the lack of jobs obstructs older adults’ inclusion in the labor market, particularly the formal component.

As mentioned earlier, the social assistance facilities encompass LEAP, EBAN elderly welfare cards, and property rebates. The interview data also shows that the social care dimension finds expression in recreational/residential/institutional homes, based on which the Henri Dei Recreational Centre located at Osu is para-statal; and privately owned nursing homes (e.g., Mercy Care Nursing Home) also pertains. However, the former is a daycare facility, whereas the latter is a residential home facility.

Discussion

Qualitatively, the results intimate that Ghana’s broader policy orientation is tilted towards children, the youth, and education, which extensively excludes older adults by a wide margin. This is largely a depiction of a gross policy exclusion for the sector of ageing and later life. Yet, the nation’s population is ageing fast, which is reminiscent of the required remedial measures’ including their installation to forestall inadequacies in service delivery to meet their heterogeneous needs.

In terms of paid work, there is massive youth unemployment with implications for the government’s decision or policy directives to adjust the retirement age upward. But few formal sector’s job avenues avail. This situation has elicited a systemic shift in sectoral choices in terms of formal to informal sector employment during post-retirement life. Ultimately, the lack of jobs obstructs older adults’ inclusion in the labor market. Ghana Statistical Services (GSS, 2013) found that older adults constitute 8.8% of the total labor force in Ghana. Further, they can undertake jobs that are not so demanding, such as getting involved in a hobby that will earn them income, so they do not depend more on others for needs provision. Despite these, there are existing legislations and policies such as the 1992 Constitution and the national ageing policy that could be beneficial to older adults in this regard. This seeks to suggest that as a nation, Ghana has good laws, legislations, and other legal instruments promulgated, yet the only challenge pertains to effective and efficient implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of these mechanisms. This particular case finds expression in the establishment of the national ageing council to oversee the implementation of the national ageing policy, as mentioned early on.

In terms of social care and incipient institutional care regime constituted by occasional, adult daycare center and residential archetypes, all of which provide a variety of care available for older adults. However, nursing homes are a relatively new phenomenon in the Ghanaian context (Dovie, 2019a).

On the whole, the skewed nature of the Ghanaian policy terrain has implications for limited resources for older adults. This is in line with Zaidi’s (2012) argument. This situation could be remedied with the enactment, including the existence of the CROP, to ensure the rights of older people are not compromised or denied them. This corroborates the findings of Wilde (2018). The skewed policy environment against older adults reflects political and/or public policy related to exclusion. The associated marginalization depicts social exclusion. The economic exclusion stands to denote inadequate state provisions for paid work for older people beyond retirement vis-à-vis the culture of the dilemma of youth unemployment heralded above -paid work for the elderly. Significantly, this study intimates that older persons suffer from vulnerabilities to economic, health, political, religious, and social dimensions. Similarly, Parmar et al. (2018) demonstrate older adults are vulnerable to social exclusion in all the social, political, economic, and cultural dimensions.

Ayalon and Tesch-Römer (2017; 2018) and Walsh et al. (2017) agree that ageist ideas pertain even in contemporary times. This necessitates a greater allure of coping strategies such as the ceragym notion, the PMS, engagement in the systemic shifts in formal and informal sector work dynamics. The opportunities component showcases the notion that policy provisions facilitate FSI development (Dovie, 2019b), including further expansion in the existing FSI, the ratification of the CROP, pensioners’ medical scheme (PMS) (Dovie, 2017; 2019a), paid work beyond pension, and the associated contribution to the economy.

The quantitative aspect of the findings shows that older adults are disposed to dementia conditions. In confirmation, Hulko, Wilson, and Balestrey (2020) argue that cases of dementia are on the rise worldwide, and health organizations in the U. S., Canada, including New Zealand, are responding to this urgent need.

By and large, the Ghanaian policy environment shapes access inequalities in the sphere of FSI, necessitating the search for coping strategies. Buffel et al. (2013) write that older individuals employ the requisite coping strategies in order to avoid exclusion. Individuals resort to coping strategies in lieu of paid work beyond pensions. In the same vein, employees undergo changing forceful social and economic conditions due to the factors of job transitions such as increased mergers, downsizing (and/or rightsizing) and restructurings in the corporate world, which denote common strategies designed as a measure to increase profit (Rudisill et al., 2010).

Theoretically, Luhmann (1997) writes that organizations follow their own rationalities, which are not always in line with the normative semantic stock of function systems. The findings show that in terms of “inclusion, exclusion, and ageing social policy” that, for this reason, function systems and organizations (e.g., the State) handle inclusion and exclusion differently, albeit rationalizing the social inclusion and exclusion issue from the viewpoint of healthcare, paid work and social care. Thus, the exclusive focus on other policy sectors in terms of inclusion is to the detriment of ageing social policy. The SWOT analysis of policy provision is a reflection of the fact that social exclusion necessitates the search for alternative measures in the form of coping strategies. This is consistent with Luhmann’s argument that social exclusion is not a problem per se, nor is inclusion always and per se unproblematic. The Luhmannian approach suggests that inclusion and exclusion are operations of social systems that treat human beings, particularly older adults, as relevant addresses for communication. Social inclusion means that human beings are held relevant in communication (Luhmann, 2005c: 226), i.e., they are considered as communicative addresses, as persons, as bearers of roles, as accountable actors (for details see Nassehi, 2002: 127). However, as Luhmann notes, ”it only makes sense to speak of inclusion if there is exclusion” (Luhmann, 2005c: 226). This is both a logical necessity as well as an empirical fact.

Interestingly, there are structural barriers to the full participation of older individuals in social and political life. The lack of adult FSI for older people in Ghana is compounded by witchcraft accusations against them, especially the women due to the pronouncements of religious leaders, especially some pastors. Older people experience pastors’ pronouncing witchcraft accusations against them, which has implications for social inclusivity. This is consistent with Wilde’s (2018) argument that barriers to social inclusion encompass religion.

The fact that international human rights laws apply to people of all ages, notwithstanding specific reference to older people, is rare. In consequence, older people’s rights are not being protected sufficiently by human rights monitoring mechanisms, governments, the human rights community as well as civil society. A case in point is the witchcraft accusations leveled against older people, including the attendant atrocities meted out to them. The protective service needs to find expression in older people’s ability to make decisions that safeguard them from circumstances of abuse, exploitation, or neglect. Special legislation and social services programs are to be provided (through the CROP) with the purpose of the protection of older people, who may be vulnerable to either physical or financial abuse, spiritual or exploitation.

There exist negative stereotypes regarding the fact that older people’s place is to rest after retirement. This depiction has been part of the Ghanaian and/or the African cultural conundrum since time immemorial. However, times have changed. Due to increased life expectancy, such stereotypic embodiment is no longer tenable. Thus, the internalization of this notion needs to be debunked. The perceived risk of conforming to negative stereotypes may culminate in further marginalization and, therefore, social exclusion of older adults from the social, economic, cultural, and political dimensions of life. This is a reflection of the stereotypic threat to older individuals. Finally, age discrimination and unfair treatment of older adults based on age in terms of access to welfare provisions are worth mentioning. Hence, these trajectories need to be challenged and reversed to facilitate the wider inclusion of older people in all facets of the Ghanaian society, including the policy environment, first and foremost. Enculturation could be used as a mechanism to eradicate such negative attitudes. These findings are consistent with the findings of the WHO (2002).

Noteworthy is that negative stereotypes of any form against older adults have ramifications of discrimination along age lines. Worldwide, age discrimination and ageism are tolerated, and older people experience discrimination as well as the violation of their rights at their family, community, and institutional levels. Further, with demographic ageing, the number of people who are likely to experience age discrimination and violation of their rights in old age may increase.

Improving the social protection of the elderly

The inadequacy of the requisite policy provisions for the older Ghanaian adult has the propensity to propel older persons to solicit alternative solution avenues in order to meet their survival needs. Yet, because these are individually motivated and based, they are usually not harmonized for the elderly person. It, however, craves the attention of the state or government regarding the need for the harmonization of these initiatives. The harmonization process may entail the provision of facilities such as seed capital for business ventures.

It is worth reiterating the fact that the lack of coherent policies for older adults is not the only challenge. This is because as a country, Ghana has woefully failed at policy implementation since independence under the government of Kwame Nkrumah, till date, policy implementation has been a bane for a long time. Ayee (2000) encapsulated this assertion in his book entitled Saints, wizards, demons, and the systems, in his explanation of the successes and failures of public policies and programs. That notwithstanding, it is a surmountable challenge that needs to be strategically overcome with due diligence.

The CROP may enable retirees and others to adjust appropriately to life in old age. Eldercare and attention have decayed or decreased drastically, leading to the proclamation of older people as witches and wizards. Such a convention will assist in facilitating the enjoyment or prevention of ambiguities to fair law and order, particularly in terms of witchcraft accusations. There is a need for proper and deeper sensitization regarding the importance of the extended family support system in satisfying the needs of the elderly. This is consistent with the argument for the strengthening of the weakened extended family system (Doh et al. 2014).

This intimates the bid of promoting adequate social protection and care for older people. The promotion and protection of the rights of older people will help provide the basic necessities they require at their old age. It will raise a sense of awareness in the working class to be responsible for dealing with older adults. The Convention will protect older people against exploitation and harsh treatments from other people, including accusers of witches and wizards. It will raise a sense of awareness in the working class to be responsible for dealing with older people through the ratification of the CROP. In effect, older people must be given more rights as their population increases to ensure that they do not suffer unfairly as a result of the absence of laws that will give them more rights (Dovie, Ohemeng, 2019).

Contributions, implications, limitations of the study

and future directions

The study has made significant contributions to the existing literature on the healthcare, paid work, and social care pillars of ageing social policy and how these shape inequalities in health and well-being. First, elderly care in the policy domain has extensively been conducted in the western world. For example, studies have been conducted in Europe, America, Asia, and including parts of Africa. It is, therefore, an oversimplification to situate the notion of social inclusion and social exclusion in the social care pillars of ageing social policy and how these shape inequalities in health and well-being as a universal concept. This present study addressed this concern by focusing on social inclusion and exclusion related to the healthcare, paid work, and social care pillars of ageing social policy and how these shape inequalities in health and well-being in Ghana.

Second, research with a special focus on the Ghanaian context provides additional insight into how social inclusion and social exclusion shape the access of the healthcare, paid work and social care pillars of ageing social policy and how these in turn shape inequalities in health and well-being in an emerging economy and how it might differ in relation to findings reported in similar studies conducted in western contexts. Third, the study highlights the benefits that the CROP will provide to older adults, especially to the plight of vulnerable older adults. Fourth, specifically, the study has contributed to the knowledge about the labor market participation dynamics of retirees and other older folks in the context of ageing social policy. Hence, the study identified paid work in later life and its associated systemic shifts.

The relevance of the study is, therefore, the identification of nodes or outlets of social inclusion and social exclusion in Ghana’s ageing social policy.

The study’s findings have some practical implications for improvements in the ageing social policy in contemporary Ghana. The study implies that social inclusion and social exclusion are not mutually exclusive; rather, one necessitates the presence of the other. For example, social exclusion may be the processor of social exclusion and vice versa. Finally, the study demonstrates logically the articulation of the three pillars of ageing social policy needs, wants, and preferences of older individuals, thereby seeking improvement in the same, including the enactment of the CROP in Ghana.

Similarly, there are some limitations to be acknowledged. First, the study was a cross-sectional study, and as a result, the dynamics of healthcare, paid work, and social care could not be studied over a longer period. Second, the examination of healthcare paid work, and social care practices could not be studied from time-to-time for determining the patterns of the practice. Third, the study does not explain the varied dimensions of healthcare, paid work, and social care in Ghana. Fourth, older people who agreed to participate were included and that the response rates varied substantially between the near-olds and elderly people.

Therefore, it is recommended that future studies about the healthcare, paid work and social care dimensions of ageing social policy in Ghana should encompass a comprehensive study of the tightening of loose ends in ageing social policy including the enactment of the CROP and redirecting policy inclusivity and equality across age categories and sectors of life in order to enhance the understanding of the influences of the concept under study. In addition, future research should concentrate on the prevalence, causes, and public discourse regarding dementia in Ghana. Finally, a similar study should explore the effects of pastoral witchcraft pronouncements against older adults, including the consequences.

***

Essentially, government policy is skewed towards children, youth gender, and education, despite older adults’ increasing population. Welfare provisions serve as a two-edged sword, which does the following: on the one hand, it projects the shallow inclusion of older adults in policy provisions. On the other hand, it also deeply excludes greater proportions of older adults from benefiting from these facilities due mostly to the notion of “age eligibility”. Yet, social inclusion and social exclusion are not mutually exclusive. Hence, for policy to promote inclusion, it must seek to improve access to resources, opportunities, and capabilities for older adults. The notion of “social inclusion” holds promise, at the level of policy and practice, for the creation of a more inclusive and equal society for older adults.

While some interventions have been made, there is still a lot to be done to improve the quality of life of the older people in the Ghanaian society as well as prepare and provide for the future growth of that segment of the population. In consequence, the government should make adequate budgetary allocations to facilitate the implementation and coordination of national policies and programs on ageing, particularly the establishment of the national ageing council to facilitate the implementation of the national ageing policy and expedite action on the enactment of the CROP. It may assist in facilitating the enjoyment or prevention of ambiguities to fair law and order.

Since Ghana’s retirement age is 60 years, the provision of older adults’ services or needs should benefit people aged 60+ rather than people aged 65+, to avert the notion of age-related discrimination and/or exclusion even among older adults themselves.

Healthcare systems will need to be responsive to the needs and demands of all persons, especially older people. The different age cohorts have different health needs. Old age comes with degenerative/non-communicable diseases with the requisite special attention, obtainable from trained healthcare professionals. Older persons require greater access to specialist healthcare services and treatment, including geriatric care. Significantly, the minimum age for beneficiaries under the NHIS exemptions should be 60 years to facilitate increased coverage of this target population. Further, the Ministry of Health and the Ghana Health Service should, as a matter of urgency, pursue the incorporation of extensive geriatric care into their health training programs and train more health workers in geriatric care to ensure prompt response to the peculiar needs of the rapidly increasing aged population in Ghana.

Alternatively, a policy to provide health insurance for those adults aged 60–69 years is worth pursuing and may need to be incorporated in the National Policy on Ageing or the law. The government’s creation of an enabling environment for older adults’ paid work beyond retirement is imperative. A similar NABSCO could make provision for a bridge job scheme for older adults in this era of increased life expectancy. Engagement in paid work in the non-farm and farming (e.g., grasscutter farming) with available support facilities, related trading, and a host of others may be useful.

References

Aboderin, I. (2006). Intergenerational support and old age in Africa. New Brunswick, NJ:

Transactions.

Anum, A., Akotia, C. S., de-Graft Aikins, A. (2019). Ageing in Ghana: A psychological study the multifaceted needs of the elderly. 5th School of Social Sciences International Conference proceedings on the theme ”Africa on the move: Harnessing socio-economic and environmental resources for sustainable transformation”. Accra: University of Ghana Printing Press.

Ayalon, L., Tesch-Römer, C. (eds.) (2018). Contemporary perspectives on ageism. Berlin: Springer.

Ayalon, L., Tesch-Römer, C. (2017). Taking a closer look at ageism: Self- and other-directed ageist attitudes and discrimination. European Journal of Ageing, 14 (1): 1–4.

Ayee, J. (2000). Saints, wizards, demons, and systems: Explaining the success or failure of public policies and programmes. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

Buffel, T., Phillipson, C., Scharf, T. (2013). Experiences of neighbourhood exclusion and inclusion among older people living in deprived inner-city areas in Belgium and England. Ageing & Society, 33 (1): 89–109.

De-Graft Aikins, A., Kushitor, M., Sanuade, O., Dakey, S., Dovie, D., Kwabena-Adade, J. (2016). Research on Ageing in Ghana from the 1950s to 2016: A Bibliography and Commentary. Ghana Studies Journal, 19: 173–189.

Doh, D., Afranie, S., Bortei-Doku Aryeetey, E. (2014). Expanding social protection opportunities for older people in Ghana: A case for strengthening traditional family systems and community institutions. Ghana Social Science Journal, 11 (1): 26–52.

Dovie, D. A., Dzorgbo, D. B. S., Mate-Kole, C. C., Mensah, H. N., Agbe, A. F., Attiogbe, A., Dzokoto, G. (2020). Generational perspective of digital literacy among Ghanaians in the 21st century: Wither now?. Media Studies J., 11 (20). DOI: 10.20901/ms.10.20.7.

Dovie, D. A. (2018a). Leveraging healthcare opportunities for improved access among Ghanaian retirees: The case of active ageing. Journal of Social Science, 7: 92. DOI: 10.3390/socsci7060092.

Dovie, D. A. (2018b). Systematic preparation process and resource mobilisation towards post-retirement life in urban Ghana: an exploration. Ghana Social Science Journal, 15 (1): 64–97.

Dovie, D. A. (2019a). The status of older adult care in contemporary Ghana: A Profile of Some Emerging Issues. Frontiers in Sociology, 4:25. DOI: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00025.

Dovie, D. A. (2019b). The influence of MIPAA in formal support infrastructure development for the Ghanaian elderly. International Journal of Ageing in Developing Countries, 3: 47–59.

Dovie, D. A., Ohemeng, F. (2019). Exploration of Ghana’s older people’s life-sustaining needs in the 21st century and the way forward. In: Tomczyk Ł., Klimczuk A. (eds.). Between successful and unsuccessful ageing: selected aspects and contexts. Kraków: Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Krakowie: 79–120. DOI: 10.24917/9788395373718.4.

GHS (2010). Center for Health Information Management Systems.

GOG (2008). National Pensions Act (Act, 766). Ghana.

GOG (2010). National ageing policy: Ageing with security and dignity. Creative Alliance, Accra.

Gooding, P., Anderson, J., NcVilly, K. (2017). Disability and social inclusion ‘Down Under’: A systematic literature review. Journal of Social Inclusion, 8 (2): 5–26.

GSS (2013). 2010 Population and housing census: National analytical report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

Hulko, W., Wilson, D., Balestrery, J. (2020). New Understandings of Memory Loss and Memory Care. Indigenous Peoples and Dementia.

Luhmann, N. (1997). Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft [The society of society]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, N. (1988). Die Wirtschaft der Gesellschaft [The economy of society]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, N. (2000a). Die Politik der Gesellschaft [The polity of society]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, N. (2000b). Organisation und entscheidung [Organization and decision]. Opladen, Germany: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Luhmann, N. (2005c). Inklusion und exklusion [Inclusion and exclusion]. In: Luhmann N. (ed.). Soziologische Aufklärung 6 [Sociological enlightenment 6]: 226–251. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS-Verlag.

MIPAA (2007). Ghana country report on the implementation of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. Accra: MIPAA.

MIPAA (2012). Ghana Country Report on the Implementation of the Madrid International Plan of Action. Accra: MIPAA.

Nassehi, A. (2002). Exclusion individuality or individualization by inclusion. Soziale Systeme, 8: 124–135.

Parmar, D., Williams, G., Dkhimi, F., Ndiaye, A., Asante, F. A., Arhinful, D. K., Mladovsky, P. (2014). Enrolment of older people in social health protection programs in West Africa – Does social exclusion play a part? Social Science & Medicine, 119: 36–44.

Peeters, H., De Tavernier, W. (2015). Lifecourses, pensions and poverty among elderly women in Belgium: Interactions between family history, work history and pension regulations. Ageing & Society, 35 (6): 1171–1199.

Rudisill, J. R., Edwards, J. M., Hershberger, P. J., Jadwin, J. E., McKee, J. M. (2010). Coping with job transition over the work life. In: Miller, T. W. (ed.). Handbook of stressful transitions across lifespan. New York: Springer, 111–131.

Walker, A. (2002). A strategy for active ageing. International Social Security Review, 55 (1): 121–139.

Walsh, K., O’Shea, E., Scharf, T., Shucksmith, M. (2014). Exploring the impact of informal practices on social exclusion and age-friendliness for older people in rural communities. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24 (1): 37–49.

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Keating, N. (2017). Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. European Journal of Ageing, 14 (1): 81–98.

Wilde, M. J., Tevington, P., Shen, W. (2018). Religious Inequality in America. Social Inclusion, 6 (2): 107–126. DOI: 10.17645/si.v6i2.1447.

WHO (2002). Active ageing: A policy framework. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zaidi, A. (2012). Exclusion from material resources: Poverty and deprivation among older people in Europe. In: Scharf T. , Keating N. C. (eds.). From exclusion to inclusion in old age: A global challenge. Bristol: Policy Press: 71–88.

1 University of Ghana, Centre for Ageing Studies, Ghana, e-mail: dellsellad@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0278-1811