4(28)2020

Jolanta Szymańska,1 Patryk Kugiel2

Development aid as a tool

of the EU’s migration policy

Abstract

Since the refugee crisis of 2015, the European Union’s institutions and EU Member States’ governments have strengthened policies to manage better migration flows and protect the EU’s external borders. In the external dimension, the Union implemented a wide variety of economic, political, and deterrence measures to regain control over migratory flows. Although development cooperation was declared one of the important tools for addressing root causes of migration, the externalization of migration management to neighboring transit countries became the main pillar of the anti-crisis strategy. Although this policy enabled to reduce essentially the number of irregular arrivals in Europe, it cannot be considered as a long-term solution. To be better prepared for migration challenges of the future, the EU should rethink its development cooperation with the origin and transit countries and include both forced and economic migrants in its comprehensive response. Aid can be a useful tool for the EU if it is used to manage rather than to stop migration.

Keywords: migration, development aid, European Union, crisis, borders

JEL Classification Codes: F22, D72, D78, K37

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2020.4.4

Pomoc rozwojowa jako narzędzie polityki migracyjnej UE

Streszczenie

Od czasu kryzysu uchodźczego z 2015 r. instytucje UE i rządy państw członkowskich wzmocniły działania na rzecz lepszego zarządzania migracją oraz ochrony zewnętrznych granic UE. W wymiarze zewnętrznym Unia zastosowała wiele różnych środków gospodarczych i politycznych, a także rozwiązań o charakterze odstraszającym, aby odzyskać kontrolę nad przepływami migracyjnymi. Chociaż współpraca na rzecz rozwoju została uznana za jedno z ważnych narzędzi eliminowania pierwotnych przyczyn migracji, to eksternalizacja zarządzania migracją do krajów tranzytowych stała się głównym filarem strategii antykryzysowej. Choć polityka ta pozwoliła zasadniczo zmniejszyć liczbę nielegalnych przekroczeń europejskiej granicy, nie można jej traktować jako rozwiązania długoterminowego. Aby lepiej się przygotować na wyzwania migracyjne w przyszłości, UE powinna przemyśleć współpracę na rzecz rozwoju z krajami pochodzenia i tranzytu oraz włączyć do swojej strategii zarówno działania wobec migrantów przymusowych, jak i ekonomicznych. Pomoc rozwojowa może być przydatnym narzędziem dla UE, jeżeli będzie wykorzystywana raczej do zarządzania niż do blokowania migracji.

Słowa kluczowe: migracja, pomoc rozwojowa, Unia Europejska, kryzys, granice

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: F22, D72, D78, K37

Introduction

Although Europe hosts the largest number of international migrants (82.3 m, or 30% of 272 m in this group), including 3.6 m of refugees (13% of global total) (UNDESA, 2019), the migration management crisis of 2015 made uncontrolled migration the top concern for the European Union (EU). In the following years, it has struggled to put in place a common policy that would both overcome internal weaknesses and enable to cope with external challenges. One of the main ideas to deal with the challenge was to “address the root causes” of migration, and one of the major tools to achieve that was through the strategic use of Official Development Assistance (ODA). It was argued that by reducing the main causes of emigration and helping people in their places of origin or transit, fewer people would be compelled to travel to Europe. Yet, aid3 was not the only instrument implemented by the EU in response to the crisis.

The European Agenda on Migration published in May 2015 (and updated in 2018) suggested several steps be taken as “immediate action” (such as saving lives at sea, targeting criminal smuggling networks, relocation of refugees) and four main pillars to “manage migration better” in the longer perspective. This included: 1) reducing incentives for irregular migration; 2) improving border management; 3) strong common asylum policy; and 4) a new policy on legal migration. As achieving progress on internal reforms (like the relocation scheme, reform of the Common European Asylum System) have proved to be difficult, the Union has focused on external activities.

This article presents the external dimension of the EU response to the 2015 crisis. It divides all instruments and policies implemented outside the Union since 2015 in practice into three broad categories: economic, political, and deterrence measures. It assesses which policies and tools helped the Union to regain control over migration and to what extent foreign aid played a role in the EU response. The article begins with a presentation of the general overview of migration flows to Europe over the last five years.

Migration to Europe since 2015

Since the peak of the migration crisis in 2015, when the number of irregular border crossings into the EU reached 1.8 m, irregular migration has been systematically falling. The total for 2019 was 139,000, 92% below the peak in 2015 (Frontex, 2019). This means that the irregular migration dropped to the levels similar to those known from the beginning of the 21st century.

Figure 1. Irregular migration in the EU, 2009–2019

Source: own work based on Frontex Risk Analysis.

While the general situation is stable, the pressure on particular migration routes differs depending both on developments in the transit regions (including the presence of smuggling networks) and EU and individual Member States’ activities on their external borders. The nationalities of migrants change over the years, depending on the situation in the countries of origin and transit. Unspecified nationals have a larger share in total detections of illegal border-crossings in the EU traditionally.

During the peak of the 2015 crisis, the highest migratory pressure was noted on the Eastern Mediterranean route (885,386 detections). Later, the Central Mediterranean route (from Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria to Italy) and the Western Mediterranean route (stretching across the sea between Spain and Morocco) became heavily traveled by irregular migrants. In early 2020 their increased pressure on Greece, borders became the main concern again as Turkey opened its borders for migrants. On the Eastern border, traffic is usually regular, and the phenomenon of irregular border crossing amounts to a fraction of a percent of the total (around 1,000 detections per year) (Frontex, 2020).

On the Eastern Mediterranean route, Syrians are the most commonly detected nationality, followed by Afghans and Iraqis. During the peak of the crisis, Syrians were also using the Central Mediterranean route with well-established smuggling networks in Libya. Currently, Tunisians and Eritreans are the two most represented nationalities on the Central Mediterranean route. Most of the migratory pressure registered in the Western Mediterranean region is linked to migrants originating from sub-Saharan countries. Eastern Borders are the entry for nationals from Ukraine, Russia, Vietnam, and Bangladesh (Frontex, 2020).

In general, one can say that nationalities using irregular routes to Europe have been changing over the years, yet most important countries of origin are clearly visible (Table 1). While most places are plagued by conflicts (Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan) or different forms of persecution (Eritrea), others gave no strong vindication for claiming asylum (such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Morocco, and Tunisia). It was also clear that most migrants, including refugees, crossed to Europe from third countries, or transit countries, rather than their homeland. This gave these transit countries (such as Turkey, Libya, Lebanon, and Morocco) a key role (of gatekeepers) in taming migration flows to the EU.

Weaker pressure on EU borders in recent years is also reflected in the numbers of people seeking international protection. Since the peak of migration influx, when the number of asylum applications between 2015 and 2016 within the EU reached the highest level of more than one m (more than double the number recorded within the EU-15 in 1992, during the previous peak), the EU has seen a drop in asylum applications. Traditionally (since 2013), Syrians have been the main group of asylum-seekers, but their share in the EU total drops. Top countries of origin also include Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. In recent years, the largest relative increases compared with previous years have been recorded for Venezuelans (Eurostat, 2020a).

Table 1. Detections of illegal border-crossing by main nationalities, 2014–2019

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

Syria – 79,169 (28%) |

Syria – 594,059 (33%) |

Not specified – 103,953 (20%) |

Syria – 19,447 (9.5%) |

Unknown – 26,203 (17%) |

Afghanistan – 34,152 (24%) |

|

Eritrea – 34,586 (12%) |

Not specified – 556,432 (31%) |

Syria – 88,697 (17%) |

Nigeria – 18,309 (8.9%) |

Syria – 14,378 (9.6%) |

Syria – 24,339 (17%) |

|

Unspecified sub-Saharan nationals – 26,341 (9.3%) |

Afghanistan – 267,485 (15%) |

Afghanistan – 54,385 (11%) |

Côte d’Ivoire – 12,913 (6.3%) |

Morocco – 13,269 (8.8%) |

Unspecified sub-Saharan nationals – 14,346 (10%) |

|

Afghanistan – 22,132 (7.8%) |

Iraq – 101,285 (5.6%) |

Nigeria – 37,811 (7.4%) |

Guinea – 12,801 (6.3%) |

Afghanistan – 12,666 (8.4%) |

Morocco – 8,020 (5.7%) |

|

Kosovo – 22,069 (7.8%) |

Pakistan – 43,314 (2.4%) |

Iraq – 32,069 (6.3%) |

Morocco – 11,387 (5.6%) |

Iraq – 10,114 (6.7%) |

Turkey – 7,880 (5.6%) |

|

Mali – 10,575 (3.7%) |

Eritrea – 40,348 (2.2%) |

Eritrea – 21,349 (4.2%) |

Iraq – 10,168 (5%) |

Turkey – 8,412 (5.6%) |

Iraq – 6,433 (4.5%) |

|

Albania – 9,323 (3.3%) |

Iran – 24,673 (1.4%) |

Pakistan – 17,973 (3.5%) |

Pakistan – 10,015 (4.9%) |

Algeria – 6,411 (4.3%) |

Algeria – 5,314 (3.7%) |

|

Gambia – 8,730 (3.1%) |

Kosovo – 23,793 (1.3%) |

Guinea – 15,985 (3.1%) |

Bangladesh – 9,384 (4.6%) |

Guinea – 6,011 (4%) |

Pakistan – 3,799 (2.7%) |

|

Nigeria – 8,715 (3.1%) |

Nigeria – 23,609 (1.3%) |

Côte d’Ivoire – 14,300 (2.8%) |

Gambia – 8,353 (4.1%) |

Tunisia – 5,229 (3.5%) |

Palestine – 3,620 (2.6%) |

|

Somalia – 7,676 (2.7%) |

Somalia – 17,694 (1%) |

Gambia – 12,927 (2.5%) |

Mali – 7,688 (3.8%) |

Mali – 4,998 (3.3%) |

Iran – 3,478 (2.5%) |

|

Others – 5,4216 (19%) |

Others – 129,645 (7.1%) |

Others – 111,922 (22%) |

Others – 84,254 (41%) |

Others – 42,423 (28%) |

All other – 3,0463 (21%) |

Source: own work based on Frontex Risk Analysis.

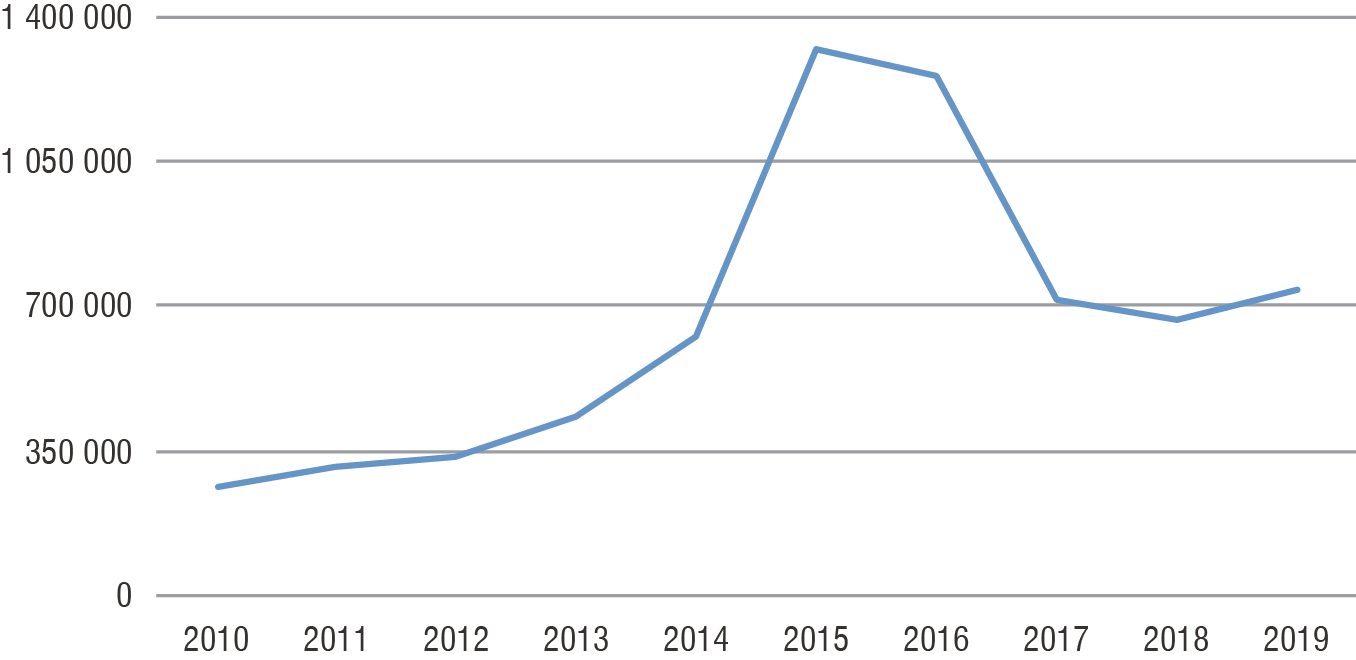

Figure 2. Asylum applications (non-EU) in the EU-28 Member States, 2010–2019

Source: Eurostat (2020a).

Although the migration debate in the EU is still dominated by issues surrounding irregular migration, considerably more migrants cross EU borders regularly. In 2018 26 Schengen states issued almost 14.3 m Schengen visas (out of over 16 m applied for) to people mostly from developing countries wishing to visit Europe legally for short stays up to 90 days (EC, 2020). It was slightly less than a year before (14.6 m in 2017) and almost the same volume as in 2015 (over 14.3 m). The drop in applications was a result of less interest among Russian nationals and the inclusion of Ukrainians into a visa-free movement regime. The general rate of rejections of visa applications in 2018 was 9.6%, up from 6.3% in 2015. Though this means a clear majority who applies for a visa can obtain it, in some countries almost half of applicants had to go away empty-handed (for instance in 2018 the refusal rate was 49.8% in Nigeria, 40.5% in Senegal, 47.8% in Iraq, 34.8% in Pakistan). Interestingly, the countries with the highest rate of rejections of applications are the same in which nationals try to reach the EU illegally.

Even more importantly, the EU Member States allow more people to settle down or stay for a longer time on their territory. In recent years, the number of first residence permits issued by Member States has been increasing, reaching the level of 3.2 m in 2018, over 1 m people more than ten years earlier (Eurostat, 2019a). Employment and family-related reasons are the key motives for applying for permits. Beneficiaries came mainly from Ukraine, China, India, Syria, Belarus, Morocco, and the USA (Eurostat, 2019a).

Figure 3. Number of first residence permits issued by reason in the EU, 2008–2018

Source: own work on the basis of the Eurostat Residence permits – statistics on first permits issued during the year, Eurostat (2019a; 2020b).

The role of aid in the EU response to migration challenges

Economic and financial means (aid, investments, trade) constituted an important element of the EU response to the 2015 refugee and migration management crisis. As the world’s largest donor,4 it is not surprising that the EC has seen financial aid in particular as a useful tool to address the root causes of irregular migration to Europe. The linking development cooperation with migration policy started already in the 1990s and was mainstreamed in the coming decades.5 In 2005, for instance, while adopting the EU Strategy for Africa, the EC president José Manuel Barroso stated that the challenges posed by immigration “can only be addressed effectively in the long term through ambitious and coordinated development cooperation to fight its root causes” (EC, 2005). This belief has been reinforced in the following EU strategic documents on migration.

The European Agenda on Migration from 2015 recognized “addressing root causes of irregular and forced displacement in third countries” as a priority action of the first pillar of the strategy: reducing the incentives for irregular migration (EC, 2015). The Commission reminded in this context that “EU external cooperation assistance, and in particular development cooperation, plays an important role in tackling global issues like poverty, insecurity, inequality, and unemployment which are among the root causes of irregular and forced migration.” A similar link between development assistance and migration interests has been made in the new European development cooperation strategy adopted in 2017 – New European Consensus for Development (in art. 41) – and was underlined in the EU Global strategy of 2016.

In reaction to the rising influx of people to Europe in 2014, the EU increased its humanitarian assistance to emergency crises in the Middle East and pledged more development assistance to support growth in the neighborhood. In addition to regular development cooperation instruments realized under the European Development Fund (in the case of Sub-Saharan Africa), Development Cooperation Instrument (for Asia), and European Neighborhood Instrument (for South Mediterranean and Eastern Neighborhood countries), new emergency mechanisms were created targeting specific needs of refugees and migrants.

Already in December 2014, the EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis was created to support host communities, refugees, and internally displaced persons in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq. At the La Valetta Summit on migration with African leaders in November 2015, the EU also established the EU Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF for Africa), aiming to “foster stability and to contribute to better migration management, including by addressing the root causes of destabilization, forced displacement and irregular migration.” Resources currently allocated to the EUTF for Africa amount to € 4.6 bn. Member States and other donors (e.g. Switzerland and Norway) have contributed € 578.5 m, of which € 511 m has been paid this far. Finally, following the deal with Turkey in March 2016, the EU started its third special instrument: The Facility for Refugees in Turkey, which offered € 6 bn to ease Turkey’s burden with hosting people displaced from Syria and the region.

The EU has also promised more investments in neighboring states. In September 2017, the organization launched its External Investment Plan (EIP) directed towards Africa and the Neighborhood. The core of EIP is over € 4.4 bn the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD), which finances guarantees and investment facilities to leverage private money to generate investments in these regions worth € 44 bn until 2020. In September 2018, EC President Jean Claude Juncker announced a new Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investments and Jobs. This upgraded version of EIP was expected to create 10 m jobs over the next five years, offer 750,000 people vocational training, and include further 100,000 students to the Erasmus program.

In addition, also the European Investment Bank created a special tool – the European Resilience Initiative to support public and private investments in Southern Neighborhood and Western Balkans to “respond to challenges such as forced displacement and migration, economic downturns, political crises, droughts, and flooding.” Also, most EU MS increased their ODA for sending and transit countries, with the “Marshall Plan for Africa” proposed by Germany as an illustrative example in early 2017 (Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development, 2017).

This money was used for a number of interventions: from providing food and shelter to refugees to creating jobs, facilitating investments, and improving border controls. The EU is generally satisfied with the outcomes of its development assistance in the context of migration challenges. The recent progress report of the Agenda of October 2019 recalled that the Facility for Refugees in Turkey is supporting almost 1.7 m refugees under 90 projects. The EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis is financing 75 projects providing support to Syrian refugees, internally displaced persons, and hosting communities across the region, and there are 210 projects in 26 countries under the EU Trust Fund for Africa delivering support to over 5 m vulnerable people (EC, 2019).

Table 2. EU Institutions Aid (ODA) commitments and disbursements to countries and regions, 2011–2018 (ODA: Total Net, USD dollars, m, 2017, constant prices)

|

Recipient |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

|

Developing Countries, Total |

commitment |

17,507.61 |

22,841.29 |

22,067.74 |

16,244.68 |

20,622.06 |

23,993.49 |

22,764.3 |

21,609.05 |

|

disbursements |

14,769.67 |

15,895.28 |

13,850.07 |

14,386.38 |

14,025.57 |

17,347.95 |

16,054.49 |

15,774.69 |

|

|

Europe, Total |

commitment |

5,349.74 |

7,329.86 |

7,002,87 |

5,527,68 |

4,566.29 |

5,346.42 |

5549.25 |

5,061.67 |

|

disbursements |

4,804.09 |

4,945.35 |

4,264.29 |

4,281.27 |

3,425.99 |

4,628.41 |

3,514.56 |

2,418.57 |

|

|

Turkey |

commitment |

2,475.74 |

3570.52 |

3,586.4 |

2,896.18 |

2,114.42 |

2,668.96 |

3,166.96 |

2,265.12 |

|

disbursements |

2,417 |

2,697.77 |

2,207.61 |

2,368.52 |

1,866.79 |

2,736.47 |

1,606.69 |

415.83 |

|

|

Africa. Total |

commitment |

5,738.9 |

8,134.5 |

7,482.77 |

4,264.37 |

7,641.85 |

10,896.68 |

8,168.37 |

7,108.89 |

|

disbursements |

5,230.95 |

6,609.75 |

5,251.3 |

5,913.96 |

5,359.84 |

6,521.54 |

6,325.53 |

6,281.16 |

|

|

North of Sahara. Total |

commitment |

1,509.6 |

2,996.51 |

1,558.81 |

1,752.03 |

1,219.5 |

1,776.87 |

1,810.82 |

1,401.61 |

|

disbursements |

1,014.47 |

1,848.58 |

1,014.83 |

1,237.11 |

980.03 |

1,501.3 |

1,275.7 |

931.38 |

|

|

South of Sahara. Total |

commitment |

4,053.11 |

4,964.2 |

5,737.57 |

1,991.45 |

4,283.05 |

7,682.44 |

5,819.03 |

4,667.24 |

|

disbursements |

3,912.39 |

4,483.43 |

3,985.04 |

4,469.12 |

4,025.28 |

4,385.36 |

4,595.23 |

4,835.84 |

|

|

Middle East. Total |

commitment |

896.56 |

944.41 |

1,394.52 |

1,365.86 |

1,618.12 |

1,371.01 |

1,354.86 |

1,477.47 |

|

disbursements |

655.63 |

681.94 |

1,022.81 |

1,095.89 |

1,237.96 |

1,549.95 |

1,427.64 |

1,599.36 |

|

Source: OECD (2020).

Nevertheless, the close linkage of development cooperation with EU migration interests stirs some controversies and is criticized by aid experts and practitioners. In the first place, many question on whether the EU has taken an extra effort to mobilize additional funding for migration-related aid. Some argue that “development aid disbursements do not generally follow root causes rhetoric” (Clemens, Postel, 2018) or that new financial instruments did not generate additional money for the ODA but rather redirect existing development funds and programs to deal with new tasks (Lehne, 2016). Indeed, the focus on support to migrants sending and transit countries in the Middle East and Africa is hardly reflected in statistics on ODA flows for last years.

The data from the OECD show that commitments of the Official Development Assistance (ODA) from EU Institutions to Sub-Saharan African countries have indeed increased astonishingly from less than 2 bn USD in 2014 to 7.6 bn USD in 2016, to decrease to 4.6 bn USD in 2018. Aid commitments to the Middle East and Northern Africa remained somehow stable (Table 2).

However, the actual flows of money show a different story and are less spectacular. Total ODA disbursements by the EU Institutions to North Africa rose from some 1 bn USD in 2014 to 1.5 bn USD in 2016 to fall to 980 m in 2018. Moreover, support to the Middle East jumped from 1.1 bn USD in 2014 to 1.6 bn USD in 2018. The ODA to Sub-Saharan Africa stayed relatively constant, fluctuating between 4.5 bn USD in 2014 and 4.8 bn USD in 2018. Naturally, one would need to add to this much bigger ODA flows from the EU MS.

Whatever overall increase in spending for these regions may reflect additional efforts undertaken in response to the refugee crisis and maybe somehow linked to migration-related assistance. The majority was used, however, for regular development cooperation programs realized with these countries. It may suggest that money for additional EU emergency trust funds was indeed redirected from the existing mechanism and not necessarily drawn from substantial extra funding.

In addition to the questions over the quantity of aid used for migration-related programs. some also raise concerns regarding the quality of that assistance. It leads to “inflation of aid,” increased conditionality and actually may cause diversion of resources from the traditional focus of development on poverty eradication (AIDWATCH. 2018). For instance,, according to recent Oxfam’s calculations. among € 3.9 bn approved for projects in Africa from the EUTF, funding for development cooperation stands at 56% of the instrument (€ 2.18 bn), while spending on migration governance reaches 26% (€ 1.011 bn) and spending on peace and security components reaches 10% (€ 382 m) of the total fund (Oxfam International, 2020). Less than 1.5% of the total worth of the EUTF for Africa was allocated to fund regular migration schemes between African countries or between Africa and the EU. Although the EU claims that its External Investment Plan is “expected to meet its objectives of to leverage total investments of more than € 44 bn” by 2020, it is not clear if that creates additional FDI in developing countries (EC, 2019). It is interesting to note that overall foreign investments to Africa went down by 10 bn USD between 2015 and 2018 from 56 bn USD to 46 bn USD, and the impact of greater European investments is not yet visible (UNCTAD, 2020).

In general, development aid plays an important role in the process of “externalization” of the EU border management by influencing migration from and the migration policies of non-EU countries, with the EU-Turkey deal being a well-known example. As a result, it may cause unintended negative consequences and lead to the securitization of development and migration policies (Bøås, Rieker, 2019). No place has this been more evident than in the Sahel, where the EU has used aid as a leverage to facilitate processes of improved border management, state capacity, and economic development in important transit countries such as Niger (Carayol, 2019; Lebovich, 2018). While representing a different kind of “agreement” than the one with Turkey, the underlying objective is the same – to reduce the number of irregular migrants heading towards Europe without paying attention to its negative impact on African countries and regional instability (Abebe, 2019).

Despite this criticism, one needs to underline that the European ODA contributed to EU migration goals in a number of ways. In the most basic dimension, as humanitarian assistance, it was crucial in addressing the needs of refugees and forcibly displaced persons to respond to emergency situations. It assisted countries in hosting a large number of refugees or transit countries to deal with this additional strain on their own resources. At the same time, aid served as an incentive and bargaining chip in relations with transit and sending countries to extract better cooperation on border control and migration management in exchange for increased financial support. Therefore, it was instrumental for the success of political aims like the deal with Turkey; similarly, aid-financed information campaigns in sending and transit countries. Most importantly, as traditional development assistance, The ODA supported numerous programs and projects targeting such root causes of migration as poverty, unemployment, and the lack of opportunities. These included interventions in the education sector, skills development, job creation, health, and many more. Aid was increasingly used as a leverage to attract private investments in Africa and the Middle East.

Political and deterrence measures in EU responses

to the 2015 migration crisis

Apart from aid and other financial instruments (FDI, trade), the EU launched a number of political initiatives to improve cooperation with third countries on migration control and management. They were designed to reduce the number of irregular arrivals in Europe but also to create legal, political, and technical frameworks for more orderly and safe migration flows.

A key to reducing migration to Europe proved to be agreements with transit countries in the Mediterranean. A statement signed by the EU and Turkey in March 2016 enabled to essentially limit the flow of migrants on the Eastern Mediterranean route to the EU. An agreement signed between Italy and Libya in 2017 (and extended in 2019) facilitated the fight against smuggling and trafficking networks in Libya and reduced irregular arrivals along the Central Mediterranean route (Michalska, Pawłowski, 2020). Strengthening cooperation between Spain and Morocco (Brito, 2019) became an effective tool to share responsibility between countries of transit and destination in the management of migrant flows.

In addition, in June 2016, the EU launched the Partnership Framework with third countries under the European Agenda on Migration. This involved several African countries, including the top 5: Niger, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and Ethiopia, and was focused on improving cooperation on migration management and on return and readmission. As a whole, this policy was often seen as an externalization of migration management, as it put more responsibility on third countries for the control of EU borders.

However, the EU approach did not always bring the expected results. The European Council’s plans to outsource asylum processing by creating centers of disembarkation outside Europe for migrants rescued at sea failed as transit countries (EU neighbors) showed reluctance to host returned migrants on their territory. Cooperation with the countries of origin, initiated by the Commission and declaratively supported by all political actors in the EU, also encountered problems. Although migration partnerships concluded with the African countries appear to be working (ICMPD, 2020), they were reluctant to enter new readmission agreements. By October 2019, it had in place formal readmission agreements or practical arrangements on return and readmission with 23 countries of origin and transit (EC, 2019). However, most of the legally binding agreements were signed before 2015 and only one – with Belarus – in January 2020. Therefore, the EU has changed its tactic to conclude informal, non-binding pacts on return and readmission procedures with several African countries (Slagter, 2019). As these turned out not very effective, the EU also engaged at a multilateral level.

Dialog on migration has been strengthened with the African Union and within several regional initiatives like Khartum Process, Rabat process. Migration has been a key area for European partners in the negotiations of the post-Cotonue agreement with the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) group of states. The EU demands on stronger cooperation on return and readmission has been one of the sticking points that made parties extend the negotiations after the Cotonou agreement expired in February 2020.

One of the sticking points remained the question of legal pathways for the safe migration of refugees. Since 2015, almost 63,000 refugees have been resettled to 20 Member States. This included 39,000 resettlements (78% out of 50,000) pledged under the general EU resettlement scheme agreed in 2015 and over 25,000 Syrian refugees under the EU-Turkey Statement since April 2016 (EC, 2019). These fewer than 25,000 resettlements to the whole EU in a year looks bleak in comparison to over 12,000 persons resettled to Australia or 28,000 to Canada in 2018 (Radford, Connor, 2019).

Moreover, the MS did not make much progress in terms of facilitating legal migration. Some exemptions include increasing the intake of foreign students to 320,000 in 2018 (from 200,000 in 2011) or starting five small pilot projects to implement circular and long-term mobility schemes for young graduates and workers from selected partner countries (Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, and Tunisia) (EC, 2019). The lack of clarity and predictability of EU policy in this regard seems to limit the willingness of third countries on better cooperation on return and readmission. It is already well understood that limited access to legal channels of migration to Europe was one of the reasons behind a rising trend of irregular entries or stays and growth in asylum applications in order to gain entry and legal status (EPSC, 2019).

Along with political initiatives, the third category of EU responses includes different actions, tools, and policies aimed at discouraging migrants from coming to the EU irregularly. This would include a number of steps to improve border security and disrupt migration routes. While the moves aimed at fighting human traffickers and dismantling smugglers networks or improving controls of the borders were presented in the context of saving the lives of migrants, they actually were also a deterrence measure.

Initially, in 2015, Frontex reinforced its operations: “Triton” in Italy and “Poseidon” in Greece. Currently, the agency is coordinating three permanent operations – Indalo in Spain, Themis in Italy, and Poseidon in Greece – and many temporary activities. In 2015 the Member States also decided to launch a naval mission in the Mediterranean aimed at human smugglers (“EUNAVFOR Med”/“Sophia” Operation). Since 2015, the operation has been expanded and renewed multiple times. However, due to some doubts about the value of the mission and broader intra-EU tensions on migration, in 2019, Member States decided to suspend their naval assets. Finally, in February 2020, European foreign affairs ministers decided to close the Sophia Operation and launch a new naval operation in the Central Mediterranean.

With limiting naval operations at the Mediterranean, restricting NGO rescue boats in the area by the Italian government and suspending the Sophia operation rescue at sea became more difficult. While the total number of drowning in the sea indeed dropped over the years (from peak 5,143 in 2016 to 1,885 in 2019) (IOM, 2020) actually, the probability of death increased (from 1.4% in 2016 to almost 2% in 2018) as much fewer people were crossing the sea. This augmented the risk of death and acted as a strong deterrent.

Finally, Europe has changed its attitude towards migration. After the initial opening of borders for Syrian refugees, since 2016 Europe has been working hard to send a different signal: that it is not any more open and welcoming to migrants. These have taken place at both national and European levels. The EU started numerous information and awareness-raising campaigns in partner countries to inform potential migrants about the risks and costs of irregular migration. Many MS introduced national numerical migration limits, cut social benefits for migrants, limited their access to healthcare systems, and examined asylum applications more restrictively. Some of the destination countries have even decided to run campaigns to change their image of “immigrant-friendly” in the countries of origin.

Conclusion: the future of the EU’s migration policy

The reduced number of irregular migration to Europe points at the relative success of the European response to the refugee crisis. Development cooperation has certainly played a role, though rather not decisive. It supported refugees and their host countries and helped in the realization of political (signing deals with third countries) and deterrence (funding information campaigns, return and reintegration programs, etc.) objectives in the EU approach. Aid laid down a foundation for long-term development, whose effects are not visible yet. Also, actual disbursements of the ODA suggest it was not the main force in changing the migration trends.

It seems that political and deterrence measures played a much more important role in stemming irregular migration. Through political engagement, the EU managed to make neighboring countries an essential part of its strategy and improve cooperation on border control and extract some commitments on return and readmission. Tightening of the migration policy promoted in the developing countries through different means sends a signal to discourage possible migrants from taking a journey to Europe. In this sense, irregular migration to Europe has not come down because the EU helped to address its main causes and push factors, but rather made migration more expansive and riskier.

The EU’s approach to irregular migration shifted from a focus on saving lives at sea to protecting European borders. Though official rhetoric around “addressing root causes” of migration fits well into an old image of the Union as soft power, it has actually acted as harder power (bribing other leaders and intimidating migrants and people willing to help them), even if that happened not in a coordinated and planned way. Although this approach may correspond well with the new vision of the “geopolitical Commission,” it is still not clear if the EU wants to be seen as turning its backs on refugees, building a “fortress Europe” and giving up on its values and adherence to international law (Dempsey, 2020).

The EU still seems not well prepared for future migration pressures. The Union signed agreements with “politically fickle, unstable, or war-torn countries,” e.g. Turkey and Libya (Sasnal, 2019). This means that control of irregular migrant flows is currently in the hands of increasingly authoritarian rulers in the European neighborhood, who repeatedly threaten to flood Europe with refugees or weak administrations in Africa’s fragile states. The recent opening of borders by Turkey in February 2020 reminded all how unsustainable that solution might be. In addition, many migrants are stuck in detention camps in highly unstable countries in the EU neighborhood. The return rate of illegal migrants is low, and effective readmission agreements are still lacking. Europe has no coherent approach to creating legal pathways to migration, and its participation in resettlement programs is not impressive. This all-in time when unfinished conflicts, demographic trends, economic growth, and climate change in Europe’s vicinity will increase the likelihood of sustained migration pressures. In the absence of legal ways of international mobility and attractive alternatives at home, many people may again turn to irregular migration to Europe.

Decreased migration pressures offer the EU to look at migration through a different lens: not only as a threat but also as an opportunity. A well designed and implemented migration policy may address the challenges of shrinking working-age population, attracting specific groups of migrants, and upholding EU international humanitarian responsibilities. The EU has two major interests in migration: to prevent irregular migration, while at the same time benefit more from regular, controlled, and safe migration. Moreover, the ODA seems a good tool, especially when it is not restricted only to stopping migration but can manage it better.

Development assistance is still the EU’s main tool in its relations with developing countries. As we showed elsewhere, some recent studies show that foreign aid can help to reduce migration flows from developing countries when it is used to improve public services or provide alternatives to migration (Kugiel, Erstad, Bøås, Szymańska, 2020). Moreover, it offers even more opportunities when it is not designed to stop migration but rather manage it and regulate it in a mutually beneficial way. Moreover, it needs to understand better how aid can be best used to respond to migration challenges.

References

Abebe, T. T. (2019, December 20). Securitisation of migration in Africa. The Case if Agadez in Niger. Institute for Security Studies, Africa Report.

AIDWATCH (2018). Aid and Migration The externalisation of Europe’s responsibilities. Brussels: Concord.

Bøås, M., Rieker, P. (2019). Executive Summary of the Final Report and Selected Policy Recommendations. Retrieved from: EUNPACK.eu (accessed: 29.07.2020).

Brito, R. (2019). Migrant arrivals plunge in Spain after deals with Morocco. Retrieved from: www.apnews.com (accessed: 29.07.2020).

Carayol, R. (2019, July 5). What Happened when the EU Moved its Fight to Stop Migration to Niger. The Nation.

Clemens, M. A., Postel, H. M. (2018). Deterring Emigration with Foreign Aid: an Overview of Evidence from Low-Income Countries. CGD Policy Paper 119.

Dempsey, J. (2020). Judy Asks: Is Europe Betraying Refugees? Brussels: Carnegie Europe.

EC (European Commission) (2005, October 12). European Commission adopts European Union Strategy for Africa.

EC (European Commission) (2015). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions A European Agenda on Migration, COM(2015) 240 final.

EC (European Commission) (2019, October 16). Progress report on the Implementation of the European Agenda on Migration Brussels, COM(2019) 481 final.

EC (European Commission) (2020). Complete statistics on short-stay visas issued by the Schengen States.

EPSC (European Political Strategy Centre) (2019). 10 trends shaping migration. Brussels: EPSC.

Eurostat (2019a). Residence permits – statistics on first permits issued during the year (accessed:

07.09.2019).

Eurostat (2019b). Non-EU citizens: 4.4% of the EU population in 2018 (accessed: 15.03.2019).

Eurostat (2020a). Asylum Statistics (accessed: 15.05.2020; 26.05.2020).

Eurostat (2020b). All valid permits by reason, length of validity and citizenship on 31 December of each year (accessed: 24.02.2020).

Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (2017). Africa and Europe – A new partnership for development, peace and a better future. Cornerstones of a Marshall Plan with Africa. Bonn.

Frontex (2019). Number of irregular crossings at Europe’s borders at lowest level in 5 years. Retrieved from: www.frontex.europa.eu (accessed: 29.07.2020).

Frontex (2020). Migratory Routes. Retrieved from: www.frontex.europa.eu (accessed: 29.07.2020).

ICMPD (International Centre for Migration Policy Development) (2020). ICMPD Migration Outlook 2019. Austria.

IOM (International Organization for Migration) (2020). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved from: www.iom.int (accessed: 29.07.2020).

Kugiel, P., Erstad, H. U., Bøås, M., Szymańska, J. (2020). Can Aid Solve the Root Causes of Migration? A Framework for Future Research on the Development-Migration Nexus. PISM Policy Paper 1 (176).

Lebovich, A. (2018). Halting Ambition: EU Migration and Security Policy in the Sahel. EU Council of Foreign Relations.

Lehne, S. (2016). Upgrading the EU’s Migration Partnerships. Brussels: Carnegie Europe.

Michalska, K., Pawłowski, M. (2020). Libya Agreement’s Impact on Italy’s Migration Policy. PISM Bulletin 20 (1450).

Morthorst, L. J., (2019). EU Policies Don’t Tackle Root Causes of Migration: They Risk Aggravating Them. Copenhagen: IPS News Agency.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2020). Aid (ODA) commitments to countries and regions. Retrieved from: https://stats.oecd.org (accessed:

29.07.2020).

Oxfam International (2020, January). The EU Trust Fund for Africa Trapped between aid policy and migration politics. Oxfam Briefing Paper.

Radford, J., Connor, P. (2019). Canada now leads the world in refugee resettlement, surpassing the U. S. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre.

Sasnal, P. (2019). Six Takeaways on European Migration Management since the Adoption of the Global Compact for Migration. PISM Strategic File 2 (90).

Slagter, J. (2019). An “Informal” Turn in the European Union’s Migrant Returns Policy towards Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) (2020). Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock. UNCTADStat.

UNDESA (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) (2019, September). Population facts, International migrants numbered 272 m in 2019 continuing an upward trend in all major world regions, 4.

1 Polish Institute of International Affairs; the University of Warsaw and National School of Public Administration, e-mail: szymanska@pism.pl, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4107-8125

2 Polish Institute of International Affairs; the University of Warsaw, e-mail: kugiel@pism.pl

3 Development aid is best understood by reference to the term “official development aid,” defined by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) as “government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries.”

4 In 2018 alone, the EU spent more than € 74.4 bn in Official Development Assistance (ODA), almost 57% of the total global development assistance by all OECD–DAC donors including € 13.6 bn in the ODA provided by EU institutions.

5 This was visible already in the EC’s comprehensive approach to migration presented in 1994 (Morthorst, 2019).