Wstęp

szpp.sgh.waw.pl

ISSN: 2391-6389

eISSN: 2719-7131

Vol. 8, No. 1, 2021, –71

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2021.1.3

Kinga Stęplewska1

Analysis of changes in the retirement insurance system in Poland in 2002–2018

Abstract

The year 1999 marked the beginning of reforms in social insurance in Poland. Changes which were implemented then regarded mainly retirement insurance. Until the reform was introduced, the retirement insurance had operated under a pay-as-you-go system. However, political changes in Poland, as well as adverse demographic trends, led to ineffective functioning of the existing system of financing liabilities arising from retirement insurance. It was necessary to introduce changes that, above all, would allow for maintaining an appropriate level of retirement pension. The following article concentrates on one selected aspect of this insurance – Open Pension Funds (in Polish: Otwarte Fundusze Emerytalne; OFEs) and presents major changes occurring in 2002–2018, their reasons and effects. The analysis is mainly based on data from the Financial Supervision Authority and the Social Insurance Institution.

Keywords: insurance, retirement insurance, public pensions

JEL Classification Codes: H55, G52

Analiza zmian w systemie ubezpieczeń emerytalnych w Polsce w latach 2002–2018

Streszczenie

W 1999 r. w Polsce rozpoczęto reformowanie ubezpieczeń społecznych. Zmiany, które wówczas zostały wprowadzone, w bardzo dużym zakresie dotyczyły ubezpieczenia emerytalnego. Do momentu przeprowadzenia reformy ubezpieczenie emerytalne było realizowane w systemie repartycyjnym. Jednak przemiany ustrojowe w Polsce, a także niekorzystne trendy demograficzne spowodowały, że przyjęty dotychczas sposób finansowania świadczeń z tytułu ubezpieczenia emerytalnego przestał sprawnie działać. Konieczne było wprowadzenie zmian, które przede wszystkim pozwoliłyby na utrzymanie odpowiedniej wysokości świadczenia emerytalnego. Artykuł koncentruje się na jednym wybranym aspekcie tego ubezpieczenia – Otwartych Funduszach Emerytalnych, przedstawiając najważniejsze zmiany w latach 2002–2018, ich przyczyny i skutki. Zaprezentowana w artykule analiza została oparta głównie na danych Komisji Nadzoru Finansowego oraz Zakładu Ubezpieczeń Społecznych.

Słowa kluczowe: ubezpieczenia, ubezpieczenia emerytalne, emerytury

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: H55, G52

Identifying the problem

Reforms in social insurance adopted in Poland in 1999 was a radical change of the existing system. Most fundamental and most difficult changes regarded retirement insurance. An all-public model was abolished in favor of a mixed public-private model, in which private bodies emerged and took responsibility for future pension benefits.

Following the political changes in Poland (i.e., after the transition from socialism to capitalism and the introduction of free-market principles) which began in 1989, the government embarked on reforming most areas of social and economic life. Initial changes regarding social insurance were implemented as early as 1990. One needs to notice that during the period of the Polish People’s Republic (1945–1989) the social insurance sector was centrally managed, and its daily running was entrusted to the Social Insurance Institution (in Polish: Zakład Ubezpieczeń Społecznych; ZUS). Pension insurance was mandatory for most of the society, i.e., all employees and their families (excluding some occupational groups, e.g., soldiers; pension insurance for farmers was a separate issue, too) (Decree of 1954, art. 1–3, 6). At first, provisions were financed with national funds, which were amassed by means of contributions payable by workers’ employment place. In 1986, for that purpose, a separate Social Insurance Fund (in Polish: Fundusz Ubezpieczeń Społecznych; FUS) was established (Act of 1986, art. 25). However, until 1999 there was no distribution of social security contributions for particular types of insurance, and its amount was not allocated to those individually insured (Fandrejewska, 2011).

Poland was struggling with rampant inflation in the first phase of its economic transformation (1989–1997). A substantial number of workplaces was liquidated, and the unemployment rate began to rise steadily. In order to limit the adverse effects of those changes, employees of companies in difficulty were given an opportunity to take early retirement (Ordinance of 1989). The same option was available to employees dismissed for other reasons (Ordinance of 1990). It all generated a significant rise in the number of pensioners and added to deterioration in the balance between the number of the insured and those who received pensions. The pay-as-you-go insurance system (operating on the principle of defined indemnity), which was then adopted in Poland, ceased to function effectively and properly perform its role.

In addition, demographic forecasts were unfavorable. Further functioning of retirement insurance being financed in such a way was impossible because it would have led to a considerable decrease in pension payouts or increased contributions towards retirement insurance. It would possibly have called for increased subsidies from the national budget. Therefore, the proposed reform of the pension system was supposed to provide the appropriate level of retirement benefits and – through a change in funding – relief to the national budget.

Eventually, the system implemented in 1999 was based on three options of putting aside financial means towards future pensions, which were labeled as “pillars.” The first pillar continued the existing public system based on the redistribution principle. Within the second pillar (belonging to the capital component), open pension funds (in Polish: Otwarte Fundusze Emerytalne; OFEs) were established, into which a part of pensionable dues was obligatorily paid (more in: Czechowska 2002: 42–43). In turn, the third pillar was based on voluntary forms of retirement insurance.

Regulations concerning OFEs were amended many times, but the essential changes regulating the operations of OFEs and participation in the second pillar were introduced in 2013. Since then, the operations of OFEs have changed their character, and the number of members joining the funds has dropped significantly.

The main objective of the study was to present changes in OFE operations and their reasons and social and economic effects with a particular emphasis on the period since 2014. After two decades of OFEs in operations, one should question if those bodies appropriately performed tasks they had been allocated. The following article consists of three parts. In the first one, the reader can find the most fundamental information on pension funds and legal changes regarding their operations. In the next section, the author focuses on data analysis depicting the condition of OFEs in the period under scrutiny. In the final part, one can find the author’s conclusions. The study analyses the period between 2002 and 2018. The analysis is mainly based on data from the Financial Supervision Authority and the Social Insurance Institution.

Some facts on Open Pension Funds (OFEs)

and the essential changes concerning their operations

As the law stands – a pension fund is a legal person whose objectives are accumulating financial means and investing it to pay it out to pension funds’ members on taking retirement (Act of 1997, art. 2). A fund is established exclusively by a pension society as open, employee, or voluntary.

Because of the nature of this study, its further sections are restricted to the presentation and analysis of only open pension funds. These funds operate mainly under two Acts: Social Security System Act (13.10.1998) and the Organization and Operation of Pension Funds Act (28.08.1997). The Open Pension Fund is established and managed for a fee by the General Pension Society (PTE; in Polish: Powszechne Towarzystwo Emerytalne). An open pension fund then constitutes a collection of individual pension accounts. On the other hand, a pension society is a financial institution managing the fund, which charges a fee from OFE members (more in: Góra, 2011: 3; Wieteska, 2011: 46). The Polish Financial Supervision Authority maintains supervision over pension funds’ and pension funds societies’ activities (in Polish: Komisja Nadzoru Finansowego; KNF) (Act of 2006).

Ever since OFEs were established (1999), many crucial changes concerning their operations have been implemented. Some of the legal acts imposing those major changes include the Act of 25 March 2011 and 6 December 2013. It must be noted that a thorough makeover of the capital pension system was initiated by the Act of 2013, which took effect on 1 February 2014. Under this Act, some OFEs assets were transferred to ZUS, and changes were made to the principles for joining OFEs, investment policy, amounts of contributions payable to OFEs, and fees charged by the PTE (Nowicki, 2014: 14; Matyjaszyk, 2016: 68).

Changes regarding participation in OFEs

Initially, participation in OFEs was mandatory for all people entering the job market as well as those already employed and born after 31 December 1968 (more in: Muszalski, 2004: 172–180). In accordance with the then binding rules, part of pension contribution was obligatorily transferred to OFEs. However, in 2014, by the new law, 51.5% of every member’s accounting units were remitted (prearranged in the order according to the type of assets) and transferred to ZUS (i.e., PLN 153.15 bn) (Act of 2013, art. 16, 23; Niżnik, 2016: 356). Those changes were widely discussed and found many supporters as well as opponents. The supporters pointed out the necessity for such changes for the sake of public finances, whereas the opponents regarded that as taking over private money without its owners’ consent.

Under the Act of 2013, the new insured were no longer obliged to join OFEs. However, every existing member had the right to opt for allocating part of their contribution to OFEs. Mandatory allocation of members’ contributions was in force until 30 June 2014, and the insured who wanted to continue saving up in OFEs had to make a suitable declaration. Meanwhile, existing OFE members remained ones in terms of contributions that were not remitted in 2014, and voluntariness concerned only further distribution of pension contribution. In case an insured individual did not make a declaration about allocating their contributions to a given OFE, these contributions were recorded in their subaccounts in ZUS (Nowicki, 2014: 22; Szyburska-Walczak, 2015: 157; Act with amendments of 1998, 21–22, art. 39 and 39b). The insured had the possibility of changing the investment method between their OFE and ZUS for the first time from 1 April 2014 to 31 July 2014 and then in the same period of 2016 (following changes were possible every four years). In total, in 2014 and 2016, declarations about allocating part of pension contributions to OFEs were signed by 16% of all OFE members (KNF(b), 2017: 17).

In accordance with present-day regulations, obtaining membership takes effect on signing an agreement with an OFE (or Act with amendments of 1997, art. 128). In contrast, OFEs must not refuse to sign an agreement with any person who expressed a wish to do so and complies with requirements stated in regulations on the social insurance system. A given person may be a member of one OFE only. A person accessing retirement insurance has four months (as of the date when insurance liability was accepted) before their decision to conclude an agreement with an OFE (Act with amendments of 1997, art. 81; Act with amendments of 1998 art. 39).

Amounts of members’ contributions allocated to OFEs

The amount of contributions allocated to OFEs has been changed several times. Initially, OFEs received 7.3% of the contribution base (legal act, 1998, art. 22). Since 2011 under the amendment to the Act on social insurance scheme, an OFE received 3.5% of the contribution base, and 3.8% (Act of 2011, art. 7) was recorded in subaccounts in ZUS.2 The reason for those changes – indicated by the legislator – was the increasing national debt brought about by allocating part of contributions to OFEs, which resulted in shortfalls in FUS, which, in turn, were eased by the national budget. Seeking changes in this respect, but at the same time aiming at maintaining a decent level of future benefits, the legislator decided to reallocate part of the contribution to a special subaccount in ZUS. Therefore, less financial means was being transferred to an OFE, and the remaining part of the contribution was deposited in an individual subaccount in ZUS (Nowicki, 2014: 12). Finally, in 2014 the level of contribution was set at 2.92%.3 It must be observed that the amount of financial means amassed by every insured individual in their account in OFEs influences future benefits paid out as a funded pension. The defined premium principle, introduced as part of the reform, implies that the benefit depends on the amount of contributions accumulated by an insurant throughout the period of insurance (Klimkiewicz, 2010: 28).

Changes to the structure of the OFE investment portfolio

The 1997 Act clearly defined the allocation of pension funds’ assets, indicating the categories of deposits, their levels, and limits. In effect, funds were obliged to invest mainly in so-called safe securities (e.g., bonds and other debt securities guaranteed by the State Treasury or the National Bank of Poland). Investing money in more risky securities, i.e., stocks and shares, was restricted by law (Act of 1997, art. 139–156; Zimny, 2011: 175). The above-mentioned arrangements secured safety but at the same time affected profitability (more in: Czechowska, 2002: 51).

Changes concerning OFEs’ allocation policy introduced in 2014 were meant to create a truly market-like character of the pension system. The amount of raised assets depends on the PTE’s investment decisions, which was granted a possibility of investing money into instruments with higher returns on assets but encumbered with higher risks as well. Such decisions aimed to improve effectiveness and increase the competitive edge between various OFEs (cf. Nowicki, 2014: 16).

It needs to be stressed that, contrary to prior guidelines, the Act of 2013 imposed a complete ban on investing OFE assets into treasury stocks, which forced a huge change in the way the PTE invested the funds’ assets (Nowicki, 2014: 18; Act of 2013, art. 4, pt. 25). Hence, a situation was avoided when a substantial part of the contribution transferred to OFEs was earmarked for purchasing treasury stocks and thus, indirectly added to increasing the public debt (Michalski, 2011: 27). Moreover, to ensure OFE assets’ security on the stock exchange, the legislator made a provision about a gradual decrease in limits on investments in stocks until the limits were removed in 2018 (since 2014–75%, next – 55%, 35%, 15%). Also, the restrictions on deposits from abroad were lifted, but there were introduced limits on investing assets into deposits denominated in foreign currencies (2014–10%, next – 20%, 30%) (Act of 2013; art. 35, KNF(b), 2014: 4). OFEs were allowed to offer in their portfolios treasury stocks, bonds issued by Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego (BGK) before 4 February 2016, however, on condition that they were purchased before 4 February 2014 and were not transferred to ZUS (KNF(b), 2017: 36).

OFEs were still obliged to provide maximum safety and profitability on deposits as OFEs were still to carry out activities within the scope of social insurance (Nowicki, 2014: 16; Act of 1997 with amendments, art. 139).

Running costs of OFEs

Running costs of OFEs include a distribution fee – deducted from monthly contributions and the management fee payable to the PTE. Initially, the legal Act did not determine any limit to the distribution fee, which resulted in some OFEs charging over 9% for it. The management fee was fixed at 0.05% net assets of the fund under management per month. In 2004, the legislators introduced a limit to the distribution fee at 7%, in 2010 at 3.5%, and in 2014 at 1.75%, respectively (Act of 1997, art. 134; Act of 2009, art. 1; Act of 2013, art. 20, pt. 20; Niżnik, 2016: 353–354). The management fees were changed in 2004, and their monthly amount was decided to be dependent on the net level of OFE assets (Act of 2003, art. 1, pt. 55). In addition, a fee was laid down to accompany opening a surplus account. The fee depended on the fund’s investment results, the value of the assets, and the rate of return (more in: Niżnik, 2016: 354).

For the clients, the management fee is particularly important as it is paid with the fund’s assets, which lowers the net value of the assets and directly affects the value of an accounting unit (VAU) and the rate of return. On the other hand, the distribution fee is a charge before the contribution is converted into accounting units; hence, the amount of this fee does not impact directly the net value of assets and the fund’s rate of return. That means, however, that the rate of return of an individual member is lower than the rate of return of a given OFE (Zimny, 2011: 174; Act of 1997, art. 134).

Until 2011 in case of changing OFEs, a member had to pay a transfer fee, and the management fee included the costs of acquisition, which in 2012 was prohibited. From then on, membership agreements have been signed by correspondence exclusively (Act of 2011, art. 4, pts. 21, 22, 29).

The method of establishing charges and their volume came under criticism, as those charges, especially in the initial period of OFE operations, presented a huge expense for the insured. By deciding on a given method of calculating management fees, the legislators secured a regular income for the PTE (more in: Wieteska, 2011: 41, 44; Michalski, 2011: 17–22). Hence, in the following years, a suggestion was put forward to make changes regarding charges and a proposal to transfer part of the contribution to ZUS, which was adopted in 2014 (cf. Michalski, 2011: 22–23).

Other changes

The amendment of 2013 changed the principles of pension payout with regard to its capital part. In accordance with initial provisions of the Act on social insurance system, pension payout was to be made through retirement insurance institutions (Act of 1997, art. 111). Finally, ZUS became the subject institution carrying out a retirement institution’s tasks. It was exclusively entitled to make retirement payments from the first and second pillars. To provide extra security against unfavorable fluctuations on the capital market, a provision was put forward saying that ten years prior to reaching the retirement age, ZUS stops transferring contributions to a given OFE, with the financial means being recorded in sub-accounts. At the same time, the OFE begins remitting accounting units and transferring financial resources to FUS (so-called security slide) (Act of 2013, art. 4, pts. 13–16, 5, pts. 3–4). However, on retirement, the total capital assembled in the OFE is transferred to ZUS or the national budget. In the first three years after the introduction of the amendments (from October 2014 to September 2017), OFEs transferred PLN 1,404 bn (KNF(b), 2014: 17).

Particularly essential for the volume of pension benefits was a change regarding the retirement age. In 2013 a process leading to the extension of the retirement age to 67 years of age (for both women and men) was started. At that time, the retirement age stood at 60 and 65 years of age, respectively. The new retirement age for men was supposed to come into effect in 2020 and in the case of women in 2040 (Act of 2012, art. 1). However, the amendment to the Act, which took effect on 1 October 2017, reintroduced the previous retirement age ruling, i.e., 60 years of age for women and 65 years of age for men (Act of 2016, art. 1).

The analysis of the situation of OFEs in 2002–2018 based on numerical data

In order to illustrate ongoing changes in the OFE market, the following analysis contains data on the number of funds, funds’ members, and accounts kept by the funds. Later on, an analysis is performed on financial data: amounts and numbers of contributions, net assets level, accounting units’ value, rate of return, and structures of investment portfolios. This analysis touches upon 2002 to 2018 (for a better presentation, the author focuses on 2-year intervals). The data presenting given funds are based on a 2018 listing of funds (considering name changes and takeovers happening in previous years). In contrast, general data in the subsequent years refer to the summation of volumes yielded by funds operating in a given year (they do not represent the summation of the presented data).

For a better understanding of developments, the economic situation in Poland is discussed in brief. From 2002 to 2007, the economic situation in Poland was good. Poland witnessed a steady rise in GDP (from 2% in 2002 to 7% in 2007, an economic slowdown to 3.5% took place in 2005). The global economic crisis, which happened after 2007, affected Poland, too. An upward trend in GDP was maintained, but its growth rate clearly dropped (from 7.4% in the 1st quarter of 2007 to 2.9% in the 4th quarter of 2008). In the following years, one could notice an economic revival (in 2018, GDP went up to 5.1%).

A crisis in the financial markets adversely affected the investment performance of financial institutions, including OFEs. In the period in question, the growth in net assets of the funds was slower than in the previous years despite higher contributions transferred to OFEs. Considerable falls in stock indices caused drops in units of account. In effect, pension funds in the period 2006–2009 yielded negative rates of return. An improvement in the stock market began in 2009, which led to increases in funds’ net assets.

The labor market situation in the period under study was improving steadily, and the unemployment rate between 2002–2018 showed a downward trend. Nevertheless, its level fluctuated over given time-periods. Between 2002 and 2005 the unemployment rate (registered one) in Poland amounted to 18%–20% and from 2003 showed a downward trend (2006–15%, 2008–9.5%, 2012–13.4%, 2018–6%). A relatively favorable situation on the labor market in the period 2006–2009, as well as a fall in the unemployment rate, resulted in an increase in the value of contributions submitted to OFEs (KNF(b), 2009: 4, 6; 2011: 4, 5; 2014: 6; 2017: 5; 2018: 5; GUS, 2018b).

The number of operating funds in the period in question

In 2002 in Poland, there were 17 OFEs in operation. In the following years, one could observe a decrease in their number – in 2004: 15, 2008: 14, 2014: 12, and in 2018: 10. In the period under scrutiny, there were changes in the ownership structure (takeovers, mergers), which led to changes in open pension funds’ names.

In 2018 the following OFEs were in operation: Nationale-Nederlanden OFE (NN), Generali OFE (Generali), PKO BP Bankowy OFE (PKO), OFE PZU “Złota Jesień” (PZU), Aviva OFE Aviva Santander (Aviva), AEGON OFE (Aegon), AXA OFE (AXA), Allianz Polska OFE (Allianz), MetLife OFE (MetLife), OFE Pocztylion (Pocztylion).

Change in the number of OFE members

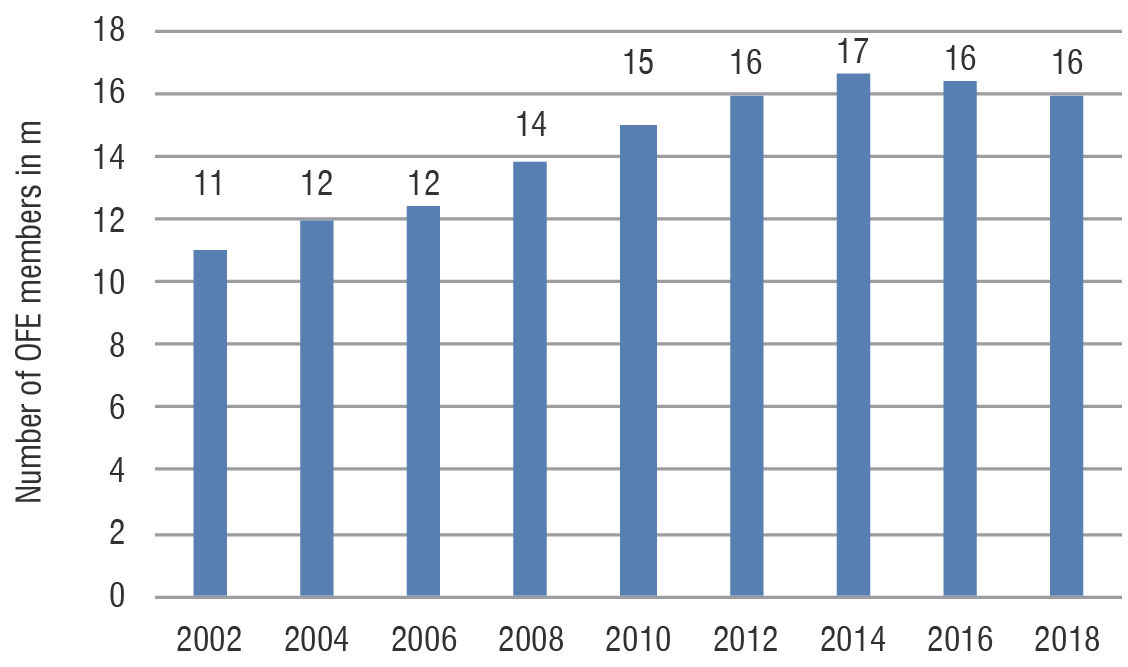

Figure 1. Number of OFE members in 2002–2018 (the status as of 31 December

of each year)

Source: own work based on data from the KNF.

The number of OFE members rose steadily until 2014 (compared to the number in 2002, it grew by 51%), and in 2016 and 2018, there was a fall in the OFE membership (Figure 1). A considerable increase in 2008 compared to 2006 (by 12%) resulted from a rising number of employees who, at the same time, fell under the obligatory social insurance. Since the obligatory OFE membership was waived (in 2014), there has been a steady drop in the membership numbers because, on the one hand, a low percentage of people decided to become a member of an OFE and, on the other hand, people left OFEs due to reaching their retirement age, death or abandoning the system (KNF(b), 2014: 6, 16; 2017: 5, 16).

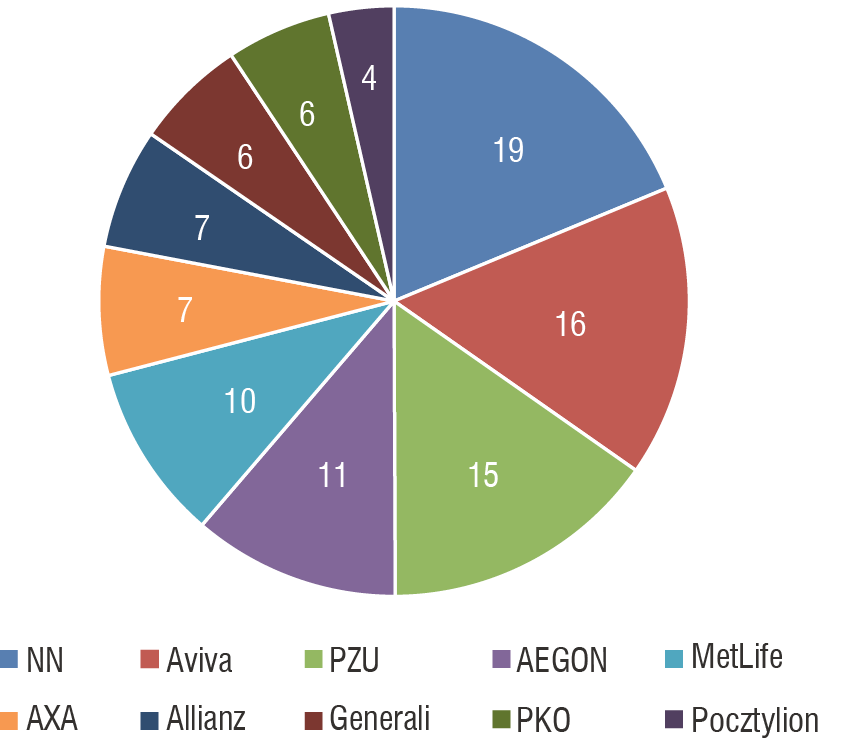

Figure 2. OFE membership structure in 2018 (%)

Source: own work based on data from the KNF.

According to data from KNF(a), in 2002, almost a quarter of OFE members belonged to Aviva, 17% belonged to NN, and 16% belonged to PZU. In 2010 NN Fund came into the lead and stayed there till 2018 (20% in 2010 and 19% in the following years). As for Aviva Fund, its share diminished to 17% in 2012 and to 16% in the following years. PZU Fund had its lowest share in 2014 and 2016 (13%), but in 2018 it sprang back to 16% (after taking over Pekao OFE). In 2018 essential shares in the total number of OFE members belonged to Aegon and MetLife (Figure 2).

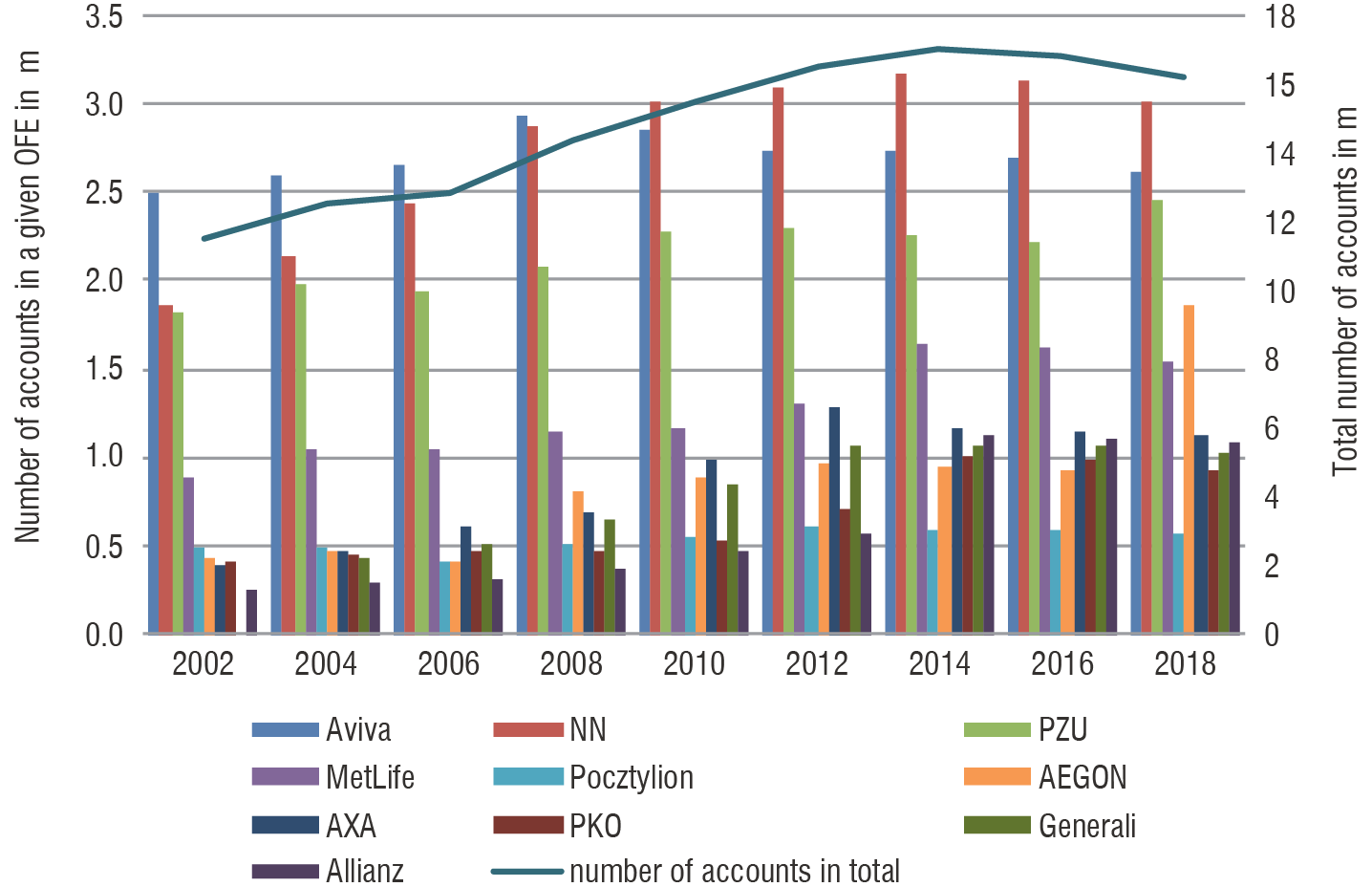

The number of accounts kept by OFEs

Until 2014 there had been a steady growth in the number of accounts in OFEs from 11.5 million to 17 million (i.e., by 49%). Taking into account biyearly changes, the highest increase of 12% was recorded in 2008 (compared to 2006). Later on (2016 and 2018), the number of accounts fell (to 16.2 million in 2018), which resulted from amendments in the legislation.

Throughout the period under scrutiny, there were three OFEs with the most substantial numbers of accounts: Aviva, NN, and PZU. In 2008 Aviva held 2.9 million accounts; in the same year, NN and PZU held 2.8 million and 2.1 million accounts, respectively. In 2010 the leading fund was NN (3 million, Aviva – 2.8 million, PZU – 2.3 million accounts). Among those three funds, there were very little fluctuations in the number of accounts. The majority of the remaining funds behaved likewise. Huge changes took place only in Allianz in 2014 and Aegon in 2018, which resulted from takeovers that these funds made (Figure 3). The percentage of inactive (dead) accounts (i.e., those which did not receive any contributions) showed a falling trend: from 18% in 2002 to 0.7% in 2018 (KNF(a)).

Figure 3. Number of accounts in OFEs in 2002–2018 (the status at the end of each year)

Source: own work based on data from the KNF.

The difference between the number of OFE members registered by ZUS and the number of accounts in OFEs stemmed from different forms of members’ registration, including inactive accounts (GUS, 2018b: 1).

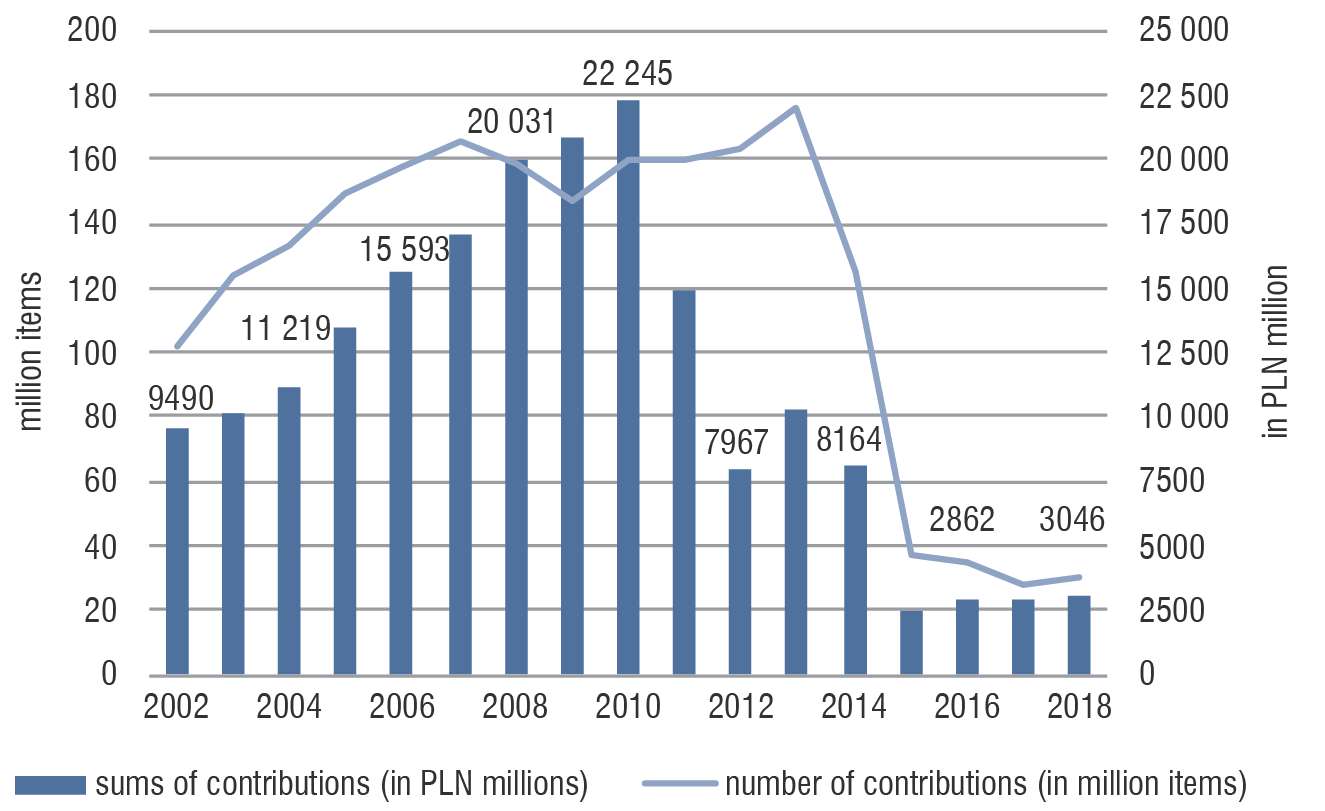

Sums and the number of pension contributions transferred to OFE by ZUS

In Figure 4 depicting aggregated data for sums and the number of contributions, one should notice a clear upward trend in the sums of transferred contributions until 2010. In total, in the year 2010, 22.2 million zlotys (PLN) was transferred to OFEs. In 2011 there was a drop of 33%. The most considerable decline of 89% in comparison to 2010 took place in 2015. After that year, the funds noted a slow growth in the following years. The highest number of contributions was handed over in 2013 (175.9 million), and the lowest one in 2017 (27.6 million).

Figure 4. Sums and the number of contributions transferred to OFEs in total

Source: own work based on data from the KNF and ZUS.

The decline after 2011 resulted mainly from a change in the level of contributions. Also, from July 2014, OFEs received contributions only from members who signed suitable declarations; in addition, from February 2014, “security slide” regulations took effect. For the first time resources under security, slide regulations were handed over in the last quarter of 2014 (for the period starting in February of that year) in the total amount of PLN 3.7 bn (i.e., 2.3% of OFEs’ net assets, as of September 2014). In turn, lowering the retirement age in 2017 immediately produced a group of pensioners and applying a “security slide” to additional younger members (KNF(b), 2014: 19; 2017: 19, 20, 21). A more detailed analysis of data from the KNF(a) discloses that the leading position in terms of the sums of contributions transferred was taken by Aviva, NN, and PZU, whose share in 2002 and 2018 amounted to 29% and 19%, 21% and 29%; 14% and 12%, respectively.

Funds’ net assets, the value of accounting units,

and the rate of return

A fund’s assets include members’ contributions and, on account of that, obtained rights and other benefits. On the other hand, net assets are assets reduced by funds’ payables. The value of accounting units is calculated with relation to net assets (it is the ratio of net assets to the number of units recorded on a given day in accounts held by a particular fund). In turn, the rate of return, according to art. 172 in the Act of 1997 (incl. amendments), is determined in percentage as the quotient of the difference between the VAU on the last day of the billing month and the VAU on the last day of the billing month prior to the 36-month period to the VAU on the last day of the billing month prior to the 36-month period. The billing months are March and September, respectively (initially, it was a 24-month period including quarters, since 2004 – it has been a 36-month period). The VAU then shows a percentage change in the value of the accounting unit and illustrates the profitability of investments made by an OFE in a particular period of time. A supervising body fixed the minimal rate of return as the weighted average rate of return for all the funds which they yielded in a specific period of time (Czechowska, 2002: 46; Zimny, 2011: 174, 176). Since 2014 the minimal rate of return has not been in force. However, the effectivity system still relies on the weighted average rate of return and the periodic rate of return (Nowicki, 2014: 18; KNF(c), 2016: 1).

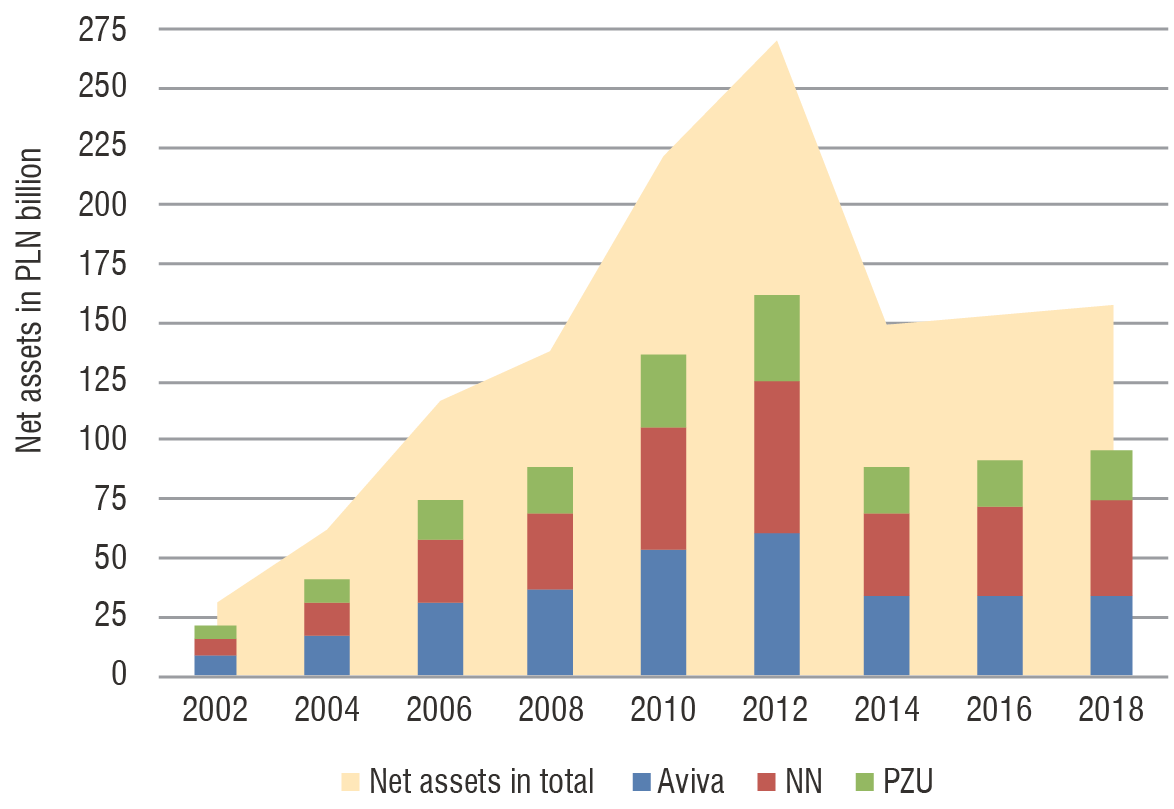

All the funds’ net assets in 2002 amounted to over PLN 31 bn, and till 2012, they noted a steady increase. The strongest growths occurred in 2004 and 2006 (in the analyzed period) (98%, 89%, compared to 2002 and 2004). A decline in the rate of growth in assets in the following period resulted from a crisis in financial markets, which negatively affected OFEs’ investment results. The stock markets’ situation began to improve in February 2009 (KNF(b), 2009 and 2011: 18). The biggest decline took place in 2014, when, compared to 2012, net assets plunged by 45%, which happened because of transferring some means to ZUS. The following years saw a slow growth (3%).

The three biggest (in terms of contribution sums) open pension funds amassed together net assets of PLN 20.5 bn in 2002. They reached the top level of assets in 2012 – PLN 161.4 bn, and in 2018 – PLN 96.4 bn, which equaled: 65%, 60%, 61% of all assets, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5. OFE net assets in 2002–2018 (the status as of 31 December of each year)

Source: own work based on data from the KNF.

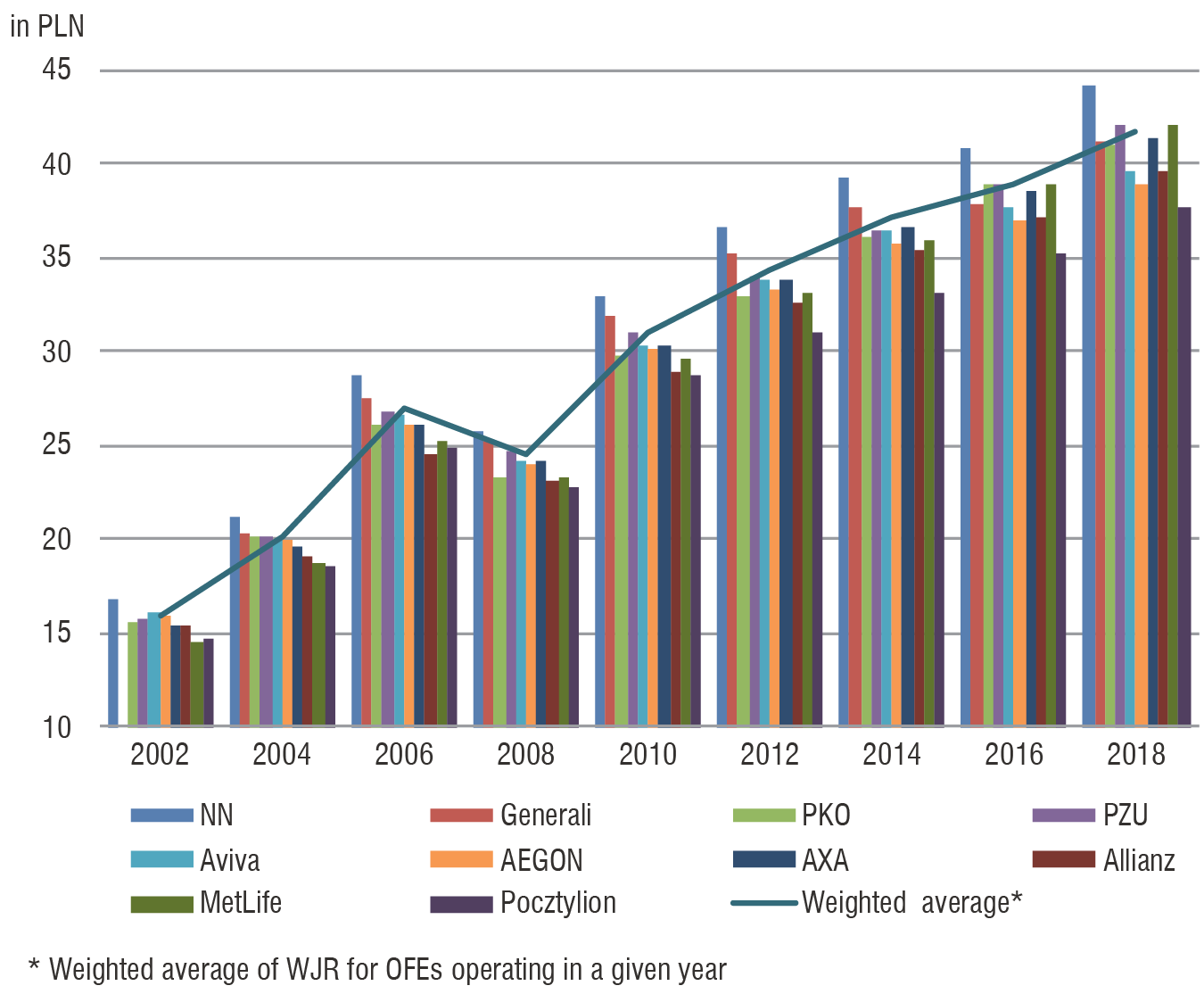

Figure 6. The value of accounting unit (as of 31 December of each year) and the weighted average of VAU in 2002–2018

Source: own work based on data from the KNF.

In Figure 6, one can see the VAU at the end of each year under scrutiny for funds operating in 2018 and the weighted average for all OFEs operating in a given year. In each year in question, the highest end-of-year value of VAU was achieved by NN. One needs to note an upward trend for VAU in respective OFEs (a decrease was noticeable only in 2008). In December 2018, the weighted average for VAU stood at PLN 41.74, which was 163% higher than in 2002. In that month, the highest VAU was achieved by NN at PLN 44.19, and the lowest by Pocztylion – PLN 37.67.

Table 1. The weighted average for the rate of return for all OFEs in a 36-month period (as of the end of September)

|

2002 |

2004 |

2006 |

2008 |

2010 |

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2018 |

|

|

The weighted average for the 3-year rate of return (%) |

- |

26.9 |

22.9 |

12.58 |

3.36 |

19.28 |

31.99 |

0.13 |

18.83 |

Source: own work based on data from the KNF and GUS.

The rate of return, which illustrates the profitability of OFE investments in a given period of time, held various values (Table 1). The lowest figures were noted in 2016, and the highest ones in 2014. 2016 witnessed a clear deterioration in financial results (they were lower only during the crisis when the weighted average in the years 2006–2009 stood at –2.93%). In the years under scrutiny, three-year rates of return stood at medium or, in some periods, very low levels, which reveals that their cost-effectiveness was low. One should observe that this paper points out only the weighted average in a 36-month period (calculated in the month of September). However, assumptions regarding OFEs were based on long-term savings. Therefore, this indicator does not fully illustrate OFEs’ effectiveness. For a more accurate picture, one could use weighted averages for longer periods, e.g., the weighted average of the rate of return for all OFEs in a 120-month period (from September 2007 until September 2017) stood at 57.5% (KNF(b), 2009: 22, 2017: 3).

While assessing the effectiveness of OFEs, one also needs to stress the importance of the PTE in the management of OFEs’ financial means. The societies were established to multiply responsibly and professionally the financial means of future pensioners. Instead, they became (especially at the beginning of their functioning) a heavy burden in terms of management fees deducted from OFEs’ assets and commissions on members’ contributions (more in: Michalski, 2011: 17–22).

OFE investment portfolios

Figure 7. Structure of OFE investment portfolios in the years 2002–2018 (%)

Source: own work based on data from the KNF.

While analyzing Figure 7, which shows investment portfolios of all OFEs, one needs to note a very distinct reorientation in the way OFEs invested their assets, which took place as a result of changes in the legislation from 2014 on. Until 2012 the portfolio had contained mainly securities guaranteed by the State Treasury and the National Bank of Poland. During the economic crisis, the amount of investment in stocks diminished. Instead, investment in the State Treasury bonds (with a fixed interest rate) became more popular. From 2009 until March 2011, there was a gradual growth in the value of stocks and shares up to almost 37%. Hence, the significance of OFEs as a participant on the Stock Exchange increased a great deal. However, OFEs still invested mainly in securities from the State Treasury. In 2011 the treasury bonds’ share went down (to 53%), primarily stemming from an investment in so-called motorway bonds (issued by the BGK and connected with road projects).

From 2014, due to amendments in the legislative, over 80% of the portfolio contained company stocks and shares as well as certificates of investment funds. Then, from February 2014, OFEs greatly changed their risk profile because they became equity funds with a much higher degree of risk from the capital-protected funds. In the subsequent periods, the structure of OFEs’ deposits was dominated by domestic shares. The improvement in the situation on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in mid-2016 contributed to an increase in share rating contained in OFEs’ portfolios and, at the same time, to an increase in the value of those portfolios up to nearly PLN 180 bn at the end of September 2017. The shares quoted on the Polish market represented 92% of OFEs’ portfolio (KNF(b), 2009: 27, 32; 2011: 28, 33, 34, 41; 2014: 5, 31, 39; 2017: 32, 33).

Running costs of OFEs

The distribution fee in 2002 ranged from 4% (Aviva) to 9% (Zurich Solidarni OFE), and the average fee was 7%. Decreases in that fee in the subsequent years were related to changes in the law. In 2004, the average went down to stand at 6.63%. In 2012, the distribution fee was similar across all OFEs (from 3.4% to 3.5%). From 2014 the majority of OFEs charged the highest allowed level (i.e., 1.75%), only Aviva and PKO charged a lower sum (0.75%, 1.70%).

The total sum of management fees charged in 2002 amounted to PLN 150.7 m, and in the following years, there was a steady growth. A monthly charge of funds’ net assets for management in 2012 (as of the end of September) ranged from 0.26‰ to 0.45‰ and amounted to PLN 1,032.4 m. In 2014 and 2016, the total for management fees decreased to PLN 778.21 m (min. 0.367‰) and PLN 694.39 m (min. 0.377‰), respectively (Niżnik, 2016: 353; KNF(c), 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018: 4, 5, GUS, 2018b)

Concepts for changes in the retirement system

A project concerning transformations in the retirement system was introduced in the Responsible Development Plan (2016), according to which an assumption was made to start a savings program dedicated to all employees. Hence, in January 2019, Employees’ Capital Programs (ECP) were developed, whose aim for the program participants is to accumulate savings systematically to receive a benefit payment on turning 60. Accumulated financial means belong to the ECP participants, and the basic contribution payment comes to 2% of their salary (Act of 2018, art. 3, 27). Participation in the ECP is voluntary. However, withdrawal from the program entails submitting a suitable declaration (Act of 2018, art. 23). Financial resources amassed within the program are meant to be invested in financial markets.

The ECP s will be formed in stages starting from the biggest employers (as of 1 July 2019) (Act of 2018, art. 134). Further changes regard transforming OFEs into specialist open investment funds. Under the project of May 2019, savings accumulated in OFEs will be handed over to private individual pensioners’ accounts at the beginning of 2020. From then on, ZUS will cease to transfer contributions to OFEs, and participants’ payments will be voluntary. However, OFE members will be allowed to submit a declaration requesting to move the Demographic Reserve Fund’s financial means. Societies will hold the individual accounts for Investment Funds, which will replace the PTE. Those changes will create a new system, which is also based on three pillars, i.e., ZUS, ECP, and individual retirement accounts, but modified versions of the existing ones (Bankier, 2019; Forbes, 2019).

* * *

Taking into account the socio-economic situation in Poland after 1989, it was necessary to adopt reforms in social insurance. Introducing an equity component into pension insurance was definitely an essential change, but the following years proved that the adopted measures had their shortcomings.

In accordance with the principles of the reform, pension funds were dedicated to amassing financial means and to investing them so that in the future, after pension funds’ members retire, funds could make payouts to them. Appropriate management of the entrusted OFEs’ finance was supposed to multiply them and increase future pensions. However, as time went by, it turned out that OFEs did not fulfill their role properly, and their profitability is too low.

Several reasons can be ascribed to that. Some of the most important ones are as follows: restrictions on methods and levels of investing OFEs’ assets, high running costs (above all, at the beginning of their operations), a non-existent direct connection between the PTE’s revenue and OFEs’ financial results, as well as unfavorable effects of the economic crisis. Those factors prevented OFEs from achieving expected financial results, and additionally, measures that were adopted added to budgetary burdens.

In view of the above, it turned out that correcting the existing ones and implementing new regulations regarding the second pillar became imperative. Profound changes were implemented in 2011, and since 2014 OFEs have been operating in a modified way. Legal changes eliminated and limited mistakes committed earlier on, and allowed for improvements in effective OFEs’ operations, but also led to increased investment risk. Moreover, the change in principles regulating membership in OFEs led to a partial shift in responsibility for the level of future pensions onto citizens themselves. At the same time, it demonstrated that a small proportion of the insured was interested in saving money within OFEs (the majority opted for keeping their pension contributions in full in ZUS). Further OFEs’ operations in the existing format stopped being reasonable. In compliance with the accepted assumptions, most probably in 2020, that is after 20 years in operations, OFEs will go out of business.

The financial status of pensioners in Poland, who rely solely on pension benefits, is still very difficult, and the forecasts are not optimistic. While analyzing demographic processes, one can expect further aging of the population, and it should be assumed that the proportion of the post-productive population in society is likely to increase. Such a situation can be accounted for by a decreasing mortality rate, which affects average life expectancy, a low birth rate, and negative population growth (GUS, 2010, 2018a, 2018b), as well as lowering the retirement age.

Forecasts point out that the proportion of the post-productive population in society will increase from 21.5% in 2018 to 24% in 2023. On the other hand, the ratio of the population in post-productive age to the population in productive age is bound to rise to 62% in 2070. (cf. in 2018, it stood at 35%) (ZUS, 2018, 13; Ministry of Finance, 2019: 32). A 2015 report for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (324) pointed out that the return on replacing gross retirement pension with earnings of an average employee taking retirement at 67 years of age in Poland will stand at 43%. This figure has worsened due to lowering the retirement age and, as forecasts say, will amount to 32% for men and 28% for women (OECD, 2017: 101).

To improve such a situation, it is necessary to take further action on pension insurance with regard to the second pillar and strengthen the third pillar, which is an optional form of putting money aside towards one’s retirement pension. The Employees’ Capital Programs that were introduced in 2019 are to increase future pensioners’ assets. As a result, an improvement in the pension replacement rate is expected to occur (Ministry of Finance, 2019: 32). In addition, it is being planned to enhance the third pillar, which is currently used by a small proportion of society (in 2018, only 9.5% of people in productive age benefitted from all forms of accumulating funds under the third pillar and referred to in the legislation; data from the KNF and ZUS). Transforming OFEs into one of the third-pillar options is believed to spark off the development of this pillar. Changes that have recently been implemented can be assessed only in a few years.

References

Czechowska, I. D. (2002). Działalność lokacyjna OFE – źródło finansowania ubezpieczeń emerytalnych. Acta Universitatis Lodzienisis. Folia Oeconomia, 160: 41–54.

Dekret z dnia 25 czerwca 1954 r. o powszechnym zaopatrzeniu emerytalnym pracowników i ich rodzin, Dz.U. 1954 nr 30, poz. 116.

Fandrejewska, A. (2011), Koniec wspólnego ubezpieczeniowego wora. Rzeczpospolita. Retrieved from: https://www.rp.pl/artykul/716065-Koniec-wspolnego-ubezpieczeniowego-wora.html (accesed: 12.09.2011).

Góra, M. (2011). Dyskusja dotycząca systemu emerytalnego – Błędna identyfikacja problemów, błędna diagnoza. Analizy, Biuro Analiz Sejmowych, 2 (46): 1–11.

Klimkiewicz, A. (2010). Charakterystyka emerytur kapitałowych finansowanych ze środków zgromadzonych w otwartym funduszu emerytalnym. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis, Folia Oeconomia, 244: 27–39.

Likwidacja OFE i opłata przekształceniowa. Poznaliśmy projekt ustawy dot. reformy emerytalnej. Forbes.pl. (2019). Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.pl/finanse/likwidacja-ofe-oplata-przeksztalceniowa-reforma-emerytalna/l5ezjhz (accesed: 29.05.2019).

Matyjaszczyk, K. (2016). Koncepcje zmian systemu emerytalnego w latach 1999–2015 w kontekście sytuacji demograficznej w Polsce. Rozprawy Ubezpieczeniowe. Konsument na rynku usług finansowych, 22 (3): 61–76.

Michalski, T. (2011). „Polski system emerytalny” – co to za konstrukcja i gdzie poprawiać? Acta Universitatis Lodziensis, Folia Oeconomia, 254: 5–35.

Muszalski, W. (2004). Ubezpieczenie społeczne. Warszawa: WN PWN.

Niżnik, J. (2016). Koszty funkcjonowania otwartych funduszy emerytalnych w Polsce. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Lublin – Polonia, L (4): 351–361.

Nowicki, D. K. (2014). Kapitałowy system emerytalny po zmianach – wybrane zagadnienia prawne. Warszawa: KNF.

Plan na rzecz odpowiedzialnego rozwoju. Uchwała nr 14/2016 Rady Ministrów z dnia 16 lutego 2016 r.

Rozporządzenie Ministra Pracy i Polityki Socjalnej z dnia 26 stycznia 1990 r. w sprawie wcześniejszych emerytur dla pracowników zwalnianych z pracy z przyczyn dotyczących zakładów pracy, Dz.U. 1990 nr 4, poz. 27.

Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 20 lutego 1989 r. w sprawie wcześniejszego przechodzenia na emeryturę pracowników likwidowanych zakładów pracy, Dz.U. 1989 nr 11, poz. 58.

Środki z OFE zostaną przekazane na prywatne Indywidualne Konta Emerytalne lub do ZUS (2019). Bankier.pl. Retrieved from: https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Premier-Srodki-z-OFE-zostana-przekazane-na-prywatne-Indywidualne-Konta-Emerytalne-IKE-7653624.html (accessed: 15.04.2019).

Szyburska-Walczak, G. (2015). Ubezpieczenia społeczne. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer.

Ustawa z 4 października 2018 r. o pracowniczych planach kapitałowych, Dz.U. 2018, poz. 2215.

Ustawa z dn. 21.07.2006 r. o nadzorze nad rynkiem finansowym, Dz.U. 2006 nr 157, poz. 1119.

Ustawa z dn. 28.08.1997 r. o organizacji i funkcjonowaniu funduszy emerytalnych, Dz.U. nr 139, poz. 933, 934.

Ustawa z dnia 11 maja 2012 r. o zmianie ustawy o emeryturach i rentach z Funduszu Ubezpieczeń Społecznych oraz niektórych innych ustaw, Dz.U. 2012, poz. 637.

Ustawa z dnia 13 października 1998 r. o systemie ubezpieczeń społecznych Dz.U. 1998 nr 137, poz. 887.

Ustawa z dnia 16 listopada 2016 r. o zmianie ustawy o emeryturach i rentach z Funduszu Ubezpieczeń Społecznych oraz niektórych innych ustaw, Dz.U. 2017, poz. 38.

Ustawa z dnia 25 listopada 1986 r. o organizacji i finansowaniu ubezpieczeń społecznych, Dz.U. 1986 nr 42, poz. 202.

Ustawa z dnia 25 marca 2011 r. o zmianie niektórych ustaw związanych z funkcjonowaniem systemu ubezpieczeń społecznych, Dz.U. 2011 nr 75, poz. 398.

Ustawa z dnia 26 czerwca 2009 r. o zmianie ustawy o organizacji i funkcjonowaniu funduszy emerytalnych oraz ustawy o zmianie ustawy o organizacji i funkcjonowaniu funduszy emerytalnych oraz niektórych innych ustaw, Dz.U. 2009 nr 127, poz. 1048.

Ustawa z dnia 27 sierpnia 2003 r. o zmianie ustawy o organizacji i funkcjonowaniu funduszy emerytalnych oraz innych ustaw, Dz.U. 2003 nr 170, poz. 1651.

Ustawa z dnia 6 grudnia 2013 r. o zmianie niektórych ustaw w związku z określeniem zasad wypłaty emerytur ze środków zgromadzonych w otwartych funduszach emerytalnych, Dz.U. 2013, poz. 1717.

Wieteska, S. (2011). Tendencje kształtowania się wysokości opłat pobieranych przez Otwarte Fundusze Emerytalne w Polsce w latach 2000–2008. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Oeconomia, 254: 37–49.

Zimny, A. (2011). Efektywność inwestycyjna OFE w świetle teorii portfela. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis, Folia Oeconomia, 259: 173–194.

Sources of statistical data:

Dane statystyczne z KNF(a) 2002–2018. Retrieved from: https://www.knf.gov.pl (accessed:

15.04.2019).

GUS (Główny Urząd Statystyczny) (2010). Komunikat Prezesa Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego w sprawie tablicy średniego dalszego trwania życia kobiet i mężczyzn. Warszawa: GUS.

GUS (Główny Urząd Statystyczny) (2018a). Komunikat Prezesa Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego w sprawie tablicy średniego dalszego trwania życia kobiet i mężczyzn. Warszawa: GUS.

GUS (Główny Urząd Statystyczny) (2018b). Wyniki finansowe otwartych funduszy emerytalnych i powszechnych towarzystw emerytalnych w 2017 roku. Warszawa: GUS.

Informacja dotycząca otwartych funduszy emerytalnych: z dnia 25 października 2012 r., z dnia 27 października 2014 r., z dnia 26 października 2016 r., z dnia 30 października 2018 r., KNF(c), Warszawa.

Informacja o działalności inwestycyjnej funduszy emerytalnych w okresie: 31.03.2006–31.03.2009, 31.03.2008–31.03.2011, 31.03.2011–31.03.2014, 31.03.2014–29.09.2017, 31.03.2015–

–31.03.2018, KNF(b), Warszawa.

Informacja o przekazywaniu składek do OFE. ZUS. Retrieved from: https://www.zus.pl/o-zus/o-nas/finanse/przekazywanie-skladek-do-ofe/2019 (accessed: 15.04.2019).

Ministerstwo Finansów (2019). Program konwergencji. Aktualizacja 2019. Warszawa: Ministerstwo Finansów.

Pensions at a Glance 2015, OECD and G20 indicators. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/pension_glance-2015-en.pdf?expires=1569840884&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=14E8255144D906B2EFBA949FF8240D21 (accessed: 15.04.2019).

Pensions at a Glance 2017, OECD and G20 indicators. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/pension_glance-2017-en.pdf?expires=1569841072&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=F70CA33E020D118E8F94F253BBFDE88B (accessed: 15.04.2019).

Podstawowe dane, Roczne wskaźniki makroekonomiczne, GUS. Retrieved from: https://stat.gov.pl/podstawowe-dane/, https://stat.gov.pl/wskazniki-makroekonomiczne (accessed: 15.04.2019).

ZUS (Zakład Ubezpieczeń Społecznych) (2018). Prognoza wpływów i wydatków Funduszu Ubezpieczeń Społecznych na lata 2019– 2023. Warszawa: ZUS.

1 Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, Poland, e-mail: kinga.steplewska@ujk.edu.pl, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2919-6812

2 As of 2011 ZUS held subaccounts, administered and managed by ZUS, which operate just like accounts in OFEs (more in: Nowicki, 2014: 5).

3 In a subaccount in ZUS the remaining part is recorded, i.e., 4.38% or the whole amount, i.e., 7.3% – in case a contribution is not allocated to an OFE (Act of 2013, art. 5, pt. 3).