- The Block Level Officer will visit the houses of the concerned senior citizens, as provided by the Returning Officers in the polling station area and deliver Form-12D to them.

- The elector has a freewill to either opt for a postal ballot or follow the normal procedure.

- If the elector opts for a postal ballot, the form will be collected from the elector within 5 days and submitted to the returning officer.

- No rallies, public meetings, street plays, Nukkad sabhas shall be allowed on any day during the days of a campaign between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. w.e.f. 7 p.m. of 16.4.2021.

- Silence period for rallies, public meetings, street plays, Nukkad Sabhas, bike rallies, or any gathering for campaigning purposes shall be extended to 72 hours before the end of the poll for Phase 6, Phase 7, and Phase 8 in the State of West Bengal. Thereby, for these phases, the campaign shall end by 6.30 p.m. on 19.04.2021, 23.04.2021, and 26.04.2021, respectively.

Studia z Polityki Publicznej

ISSN: 2391-6389

eISSN: 2719-7131

Vol. 9, No. 1, 2022, 33–53

szpp.sgh.waw.pl

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2022.1.2

Hepzibah Beulah C

Chennai Dr. Ambedkar Government Law College, Pudupakkam, India, e-mail: hepzibah.peter@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7136-2146

Pandemic challenges vs. public policy: reflections on the electoral administration in the world’s largest democracy

Abstract

Democratic elections pose an immense challenge to any government during an emergency crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. More so for a country like India, with close to 18% of the world’s population comprising an equally daunting and eager voter base of around 911 million in the time of a raging virus, both in the urban and rural areas of the nation. The first democratic large-scale election during the pandemic was successfully held in the state of Bihar in North India with more than 90 million voters, which was an astonishing feat by itself. The model followed by South Korea with the highest voter turnout provided an insight to the Indian authorities on conducting the elections. The Indian Election Commission, an independent statutory body which is entrusted with the task of conducting free and fair elections, allowed for the virtual mode of campaigning, and specific guidelines for polling were recommended. The rule changes have profound implications in significantly reducing crowded campaigns, which was synonymous with Indian democracy. The traditional lens through which the administration of elections was perceived has undergone a paradigm shift during the pandemic. New insights might surface if the electoral administration is reviewed in this study on an argumentative basis against the background of the big steps taken by the Indian election machinery. The aspects on which the research debates include: (i) the pros and cons of the action taken by the regulators; (ii) positive and negative responses from the political parties; and (iii) health and safety of the voters. The study concludes by affirming with data on the success of the Bihar Election and the wise choice of the Indian government in seizing the opportunity by taking the cues from South Korea.

Keywords: Electoral Administration, India, virtual campaign, voter safety, pandemic election

JEL Classification Codes: D72, D78, I18

Pandemiczne wyzwania a polityka publiczna. Refleksje nad administracją wyborczą w największej demokracji świata

Streszczenie

Demokratyczne wybory stanowią ogromne wyzwanie dla każdego rządu podczas kryzysu, np. pandemii COVID-19. Szczególnie w kraju takim jak Indie, w którym blisko 18% światowej populacji stanowi zarówno niechętną, jak i chętną do głosowania bazę około 911 mln ludzi w czasie rozprzestrzeniania się koronawirusa zarówno na obszarach miejskich, jak i wiejskich kraju. Pierwsze demokratyczne wybory na dużą skalę podczas pandemii z powodzeniem odbyły się w stanie Bihar w północnych Indiach z udziałem ponad 90 mln wyborców, co samo w sobie było zdumiewającym wyczynem. Model przyjęty przez Koreę Południową cechujący się najwyższą frekwencją dał wgląd władzom indyjskim w przebieg wyborów. Indyjska Komisja Wyborcza, niezależny organ statutowy, któremu powierzono zadanie przeprowadzenia wolnych i uczciwych wyborów, zezwoliła na wirtualny tryb prowadzenia kampanii i zarekomendowała konkretne wytyczne dotyczące głosowania. Zmiany zasad niosą głębokie implikacje dla znacznego ograniczenia zatłoczonych kampanii, co było synonimem indyjskiej demokracji. Administracja wyborcza została przeanalizowana w tym badaniu na tle wielkich zmian w indyjskiej machinie wyborczej. Aspekty, które podejmuje niniejsze badanie, obejmują: (i) zalety i wady działań podejmowanych przez regulatorów; (ii) pozytywne i negatywne reakcje partii politycznych; oraz (iii) zdrowie i bezpieczeństwo wyborców. Badanie kończy się potwierdzeniem danych na temat sukcesu wyborów w Bihar i mądrego wyboru rządu indyjskiego, który wykorzystał okazję, kierując się wskazówkami z Korei Południowej.

Słowa kluczowe: administracja wyborcza, Indie, wirtualna kampania, bezpieczeństwo wyborców, wybory w pandemii

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: D72, D78, I18

Elections in India are grand events with billboards, posters, mass rallies, and public meetings with star campaigners heralding for the respective parties. A free and fair election is envisaged by the Constitution of India (Chakravarty, 1997). The pandemic has made the authorities rename it into free, fair, and safe elections. The Election Commission of India, inspired by the South Korean election and with the guidance from other nationalities, released the election guidelines for Bihar in the month of August 2020. The exhaustive guidelines were not put in use by the parties strictly and, therefore, remained on paper. The Bihar election did not have a negative impact in as much as the pandemic curve in the country was at its lowest, and thus the non-adherence to the guidelines was brushed aside. The subsequent announcement of the state elections in West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Pondicherry, and Assam had the greatest impact on the people and the country. The elections are prima facie alleged to be the sole reason for the sudden spike in COVID-19 cases and the second wave hitting the country hard enough to make it gasp for breath.

The Election Commission of India studied the mode of conducting the elections during the pandemic from the other nations and had the guidelines framed for pre- and post-election formalities with appropriate instructions and directions to the authorities and the parties. The argument rests on the lack of enforcement of the guidelines by the authorities. The lethargic attitude in not handling the situations where the rules were flouted with penal actions led to the drastic failure of the mechanism pre- and post-elections.

Historical background to elections in India

The word ‘election’ includes the process involved, and the procedures followed as enumerated by the Constitution (Kanhaiyalal Omar v. R. K. Trivedi, 1986; V. S. Achuthanandan v. P. J. Francis, 1999). Article 324 of the Constitution of India provides for the creation of the Election Commission as an independent body. The words ‘superintendence, direction, and control’ empower the Election Commission to act in contingencies not provided for by law. The words ‘control,’ ‘conduct of elections,’ and ‘superintendence’ are the broadest terms which would include the power to make all provisions that are necessary for the smooth conduct of elections (Mohinder v. Chief Election Commissioner, 1988). The Election Commission of India observed in its report after the first general elections in independent India 1951–52: even in the 4th Century BC, there was a republic federation known as the “Kshudrak-Malla Sangha,” which offered strong resistance to Alexander the Great. The complete details of the Republican forms of government in ancient India are not available. However, every male member had the right to vote and to be present in the general assembly. A vote was known as ‘Chhanda,’ which means a ‘wish.’ There used to be multi-colored voting tickets called ‘shalakas’ (Kaushik, 1982; Chaudhuri, 1999; Gadkari, 1996; Shakdar, 1992; Rijhwani, 1996).

During the British rule, the Indian Councils Act 1861 and 1892 provided for legislative bodies that had no representation from the local bodies. It was only before independence that the elections to the Constituent Assembly were held and completed, and by the end of August 1946, all the 296 representatives of the British provinces had been elected. The Constitution of India, which came into force on 26th January 1950, provides for an electoral mechanism in India to be supervised and controlled by the Central Election Commission and the State Election Commission. A special chapter was devoted to elections in Part XV of the Constitution.

Elections in India

The Election Commission has been vested with quasi-judicial powers by the Constitution. Under Art 329 (b) once the process of election commences in a constituency, the courts cannot interfere until it is complete and culminates in the declaration of the election results. The Constitutional body has immense powers in conducting the elections, and there is no supervisory intervention by the Judiciary or the Executive. The Election Commission of India has the sole responsibility for preparing the electoral rolls until the official announcement of the elected candidates.

A general electoral roll is prepared by the Election Commission (Art 325) on the basis of applications received, and the draft rolls are prepared in convenient parts and in such languages as the Election Commission may direct. The draft rolls so prepared are then published for inviting claims and objections in the same manners as the draft rolls for assembly constituencies. After the allotment of the seats and the announcement of the candidates fielding in the constituency, the campaigning begins. Originally, the minimum campaign period for any election from a parliamentary, assembly, or council constituency was 30 days; it was reduced to 20 days in 1956, and now it is 14 days since August 1996.

The Model Code of Conduct for the guidance of political parties and candidates is a unique document evolved with the consensus of political parties in India and is a singular contribution by them to the cause of democracy and to strengthen its roots in the political system of the country. The Election Commission has always taken the view that the Model Code comes into operation right from the day the election schedule is announced by it (Election Commission of India, 1997). Virtual campaigning is not new to the Election Commission of India, as campaigning through the media has already been regulated by the body. The Election Commission has provided a scheme to campaign through Doordarshan and All India Radio. The election Commission issued an order on 13 January 1994, regulating the use of loudspeakers for election campaigns (Election Commission of India, 1998). In 1994, the Supreme Court modified the order and permitted the use of loudspeakers between 6.00 a.m. and 10.00 p.m. (Election Commission of India, 1994; Noise Pollution (Regulation and Control) Rules, 2000). In 2005, the Supreme Court gave a direction for universal application of the loudspeakers and stated that it shall not be permitted between 10.00 p.m. and 6.00 a.m. With the said restrictions in timing, the parties are free to use loudspeakers while campaigning.

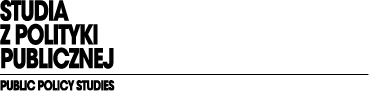

Virtual elections in India: possibilities vs. probabilities

India has over 560 million Internet subscribers (2018), second only to China. Indian mobile data users consume 8.3 gigabits (GB) of data each month on average. In the year 2018, 12.3 billion apps were downloaded, 560 million people subscribed to the Internet, 354 million people used smartphone devices, and 294 million users engaged in social media (McKinsey Global Institute, 2019). India is the second-fastest digital adopter among 17 nations (Figure 1). As per reports received from 358 operators as compared to 360 operators, the total number of Internet subscribers increased from 743.19 million at the end of March 2020 to 749.07 million at the end of June 2020, with a quarterly growth rate of 0.79%. Out of total 749.07 million Internet subscribers, 698.23 million were broadband subscribers, and 50.84 million were narrowband subscribers. Wired Internet subscribers increased from 22.42 million at the end of Mar 2020 to 23.06 million at the end of June 2020, with a quarterly growth rate of 2.86%. Wireless Internet subscribers increased from 720.78 million at the end of March 2020 to 726.01 million at the end of June 2020, with a quarterly growth rate of 0.73% (TRAI, 2020).

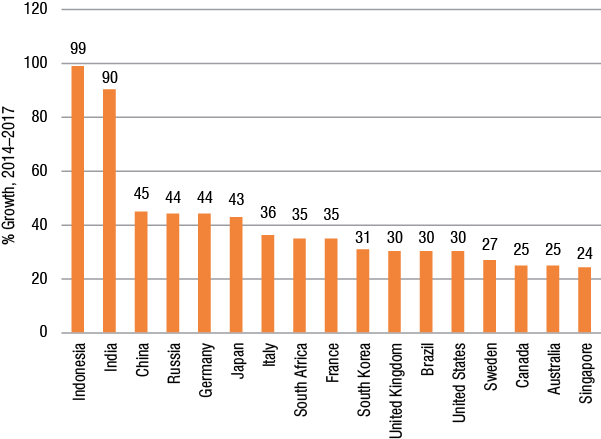

Internet penetration in Bihar is 37% and smartphones are used by 27% of the state’s population. 20.6% of the women and 43.6% men in Bihar between the age-group of 15–49 years have used the Internet. The lowest Internet usage among men is seen in Meghalaya, Assam, and Bihar. The rural-urban Internet subscriber base in India (Table 1) shows the active participation of the population in Internet usage. The possibility of routing a major part of campaigning through the virtual mode was not a far reality. The rural number is also significant, and this warrants for the guidelines to stress more on virtual campaigning to a larger extent. An advisory or observer was sufficient to monitor the contents of the campaign and the penal actions to rest with the Election Commission of India.

Figure 1. Growth in the Country Digital Adoption Index (2014–2017)

Source: own elaboration based on Akamai (2014, 2017).

The male and female ratio of Internet users in India is at a higher rate compared to other developing countries, and the states have lower variance of Internet usage between male and female citizens (Figure 2).

Table 1. Break-up of the rural-urban Internet subscriber base (in millions) (2020)

Service Area Narrowband Broadband Total (June 2020) Total (March 2020) Rural Urban Rural Urban Rural Urban Rural Urban Bihar 3.045 1.149 28.634 16.761 31.679 17.91 30.533 17.862 West Bengal 1.856 0.868 15.087 15.78 16.942 16.648 16.647 16.353 Tamil Nadu 1.414 2.286 12.383 34.959 13.797 37.245 13.819 37.819 Kerala 0.711 0.947 10.477 15.316 11.188 16.263 10.754 15.793 Assam 0.607 0.329 7.96 5.567 8.567 5.896 8.313 5.934

Source: own elaboration based on TRAI (2020).

Figure 2. Percentage of Internet users in India (male and female) (2020)

Source: own elaboration based on NFHS (2021).

Composition of state legislatures

The Central Election Commission conducts the national elections and the elections for the state assemblies are conducted by the State Election Commission. The legislature of a state consists of:

a) The Governor of the state-appointed by the Union government.

b) There are two houses in some states and one house in all the remaining states (Art 168 (1)).

The election for the state legislative assembly was conducted in the state of Bihar, West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, and Assam. The election procedure followed, as well as the outcome and the findings and suggestions form the methodology of the study.

Pre-election guidelines

The Election Commission of India released the Broad Guidelines for the conduct of general elections/bye-elections during COVID-19 (Election Commission of India, 2021a, 2021b). The important guidelines which were flouted by the parties are analysed below.

General guidelines

-

a. Every person shall wear a face mask during every election-related activity. Although this was emphasized for the campaigners and the supporters, it was widely noted in all the states that the campaigners and the star campaigners did not adhere to wearing the masks when amidst the general public. An application was filed by Mr. Vikram Singh before the Delhi High Court emphasizing that the leaders are flouting the rules by not wearing the masks during election campaigns (Singh, 2020; The Hindu, 2021b).

-

b. Social distancing to be maintained throughout the election process:

The Election Commission of India warned the political parties of flouting the COVID-19 norms reiterating the guidelines issued in August 2020 (The Hindu, 2021a).

-

c. The number of persons to accompany a candidate for the submission of nomination:

It was restricted to two (2) (this is in supersession of existing Para. 5.8.1 of the Returning Officer’s Handbook 2019) and a number of vehicles for the purposes of nomination is restricted to two (2) (this is in supersession of existing Para. 5.8.1 of the Returning Officer’s Handbook 2019).

Polling station arrangements

In the rural areas, the amenities provided to the Presiding Officer and the Polling Officers were limited. The resources were insufficient to follow the guidelines. There was a requirement to sanitize the polling station, preferably a day before the poll. The agents of the contesting parties arranged for the sanitation, which did not meet the standards set by the Commission. There were no thermal scanners at a majority of the polling stations. The Presiding Officer and the Polling Officers were directly involved in the issuance of polling slips, verifying the identity, marking with ineligible ink, and assisting the voter in using the electronic voting machine. There were other officials to assist at the polling station on the sanitary measures.

The Broad Guidelines also included the following conditions: “Help Desk for distribution of tokens to the voters of the first come first served basis so that they do not wait in a queue. Marker to demonstrate social distancing for a queue. Earmarking circle for 15–20 persons of 2 yards (6 feet) distance for voters standing in the queue depending on the availability of space. There shall be three queues each for males, females, and persons with disabilities/senior citizen voters. The services of Block Level Officers, volunteers, etc., may be engaged to monitor and regulate social distancing norms strictly. One shaded waiting area with chairs, dari, etc. will be provided, for males and females separately, within the polling station premises so that voters can participate in voting without safety concerns. Wherever possible, Booth App shall be used at the polling station. Soap and water shall be provided at the entry/exit point of every polling station. Sanitizer should be provided at the entry/exit point of every polling station” (Election Commission of India, 2021b). In the urban areas, these guidelines were followed to some extent, whereas in the rural areas the polling booth looked similar to pre-pandemic elections.

Poll workers, in particular, play a vital role in building confidence around electoral processes (Hall et al., 2009). Elsewhere, as in Germany, Spain, and Mexico, poll workers are citizens who are compelled to undertake the task as a civic duty akin to jury service and not paid much, if at all (James, Alihodzic, 2020). In India, the government officers are poll workers and, in the elections conducted during the pandemic, the training was provided to the officers in different locations. The guidelines required the poll workers to be treated as frontline workers and to be provided with face masks, gloves, and other sanitation requirements. The reality remained that the poll workers had to report to the polling station the day before the election as in all other normal elections, with no kit for the Polling Officers as provided in the guidelines.

Vote by postal ballot

The postal ballot system is available to a class of people as provided in Section 30 of the Representation of People Act, 1951 as per the provisions in Part-IIIA of the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961. The Election Commission of India issued instructions to the Chief Electoral Officers in providing the postal ballot facility for senior citizens (above 80 years) (Election Commission of India, 2020a).

The polling teams who will be delivering and collecting the postal ballot on a pre-informed date are fixed by the Returning Officer (Election Commission of India, 2020b). In Bihar, the Chief Electoral Officer issued a letter to issue and collect Form 12‑D to senior citizens (above 80 years of age) and persons with disabilities (State Election Commission, 2020). The awareness about the extension of the postal ballot system to senior citizens and persons with disabilities was not raised by the authorities.

Election campaign

The door-to-door campaign was restricted to a group of 5, including the candidate, and in the road shows: “The convoy of vehicles should be broken after every 5 (five) vehicles instead of 10 vehicles (excluding the security vehicles, if any). The interval between two sets of convoys of vehicles should be half an hour instead of gap of 100 meters” (Election Commission of India, 2021b). In a country like India, with a huge number of supporters for political parties, these guidelines were flouted by all the major parties. The guidelines also suggested the following: “Election meetings – public gatherings/rallies may be conducted subject to adherence to extant COVID-19 guidelines. The District Election Officer should take the following steps for this purpose: (a) The District Election Officer should, in advance, identify dedicated grounds for a public gathering with clearly marked entry/exit points. (b) In all such identified grounds, the District Election Officer should, in advance, put markers to ensure social distancing norms by the attendees. (c) The Nodal District Health Officer should be involved in the process to ensure that all COVID-19 related guidelines are adhered to by all concerned in the district. (d) The District Election Officer and District Superintendent of the Police should ensure that the number of attendees does not exceed the limit prescribed by the State Disaster Management Authority for public gatherings” (Election Commission of India, 2021b).

The ground reality remained that the public gatherings were in numbers beyond the control of the enforcement authorities, especially in the states such as West Bengal (Down to Earth, 2021).

Supplementary guidelines (Election Commission of India, 2021a, 2021b)

1. Positively followed in the election process

-

a. Initiatives were taken for generating intense awareness among voters and all stakeholders connected to the election process regarding the process of fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic.

b. The maximum number of electors per booth was reduced to 1,000 from 1,500.

c. Facilities of casting a postal ballot were extended to persons with disabilities (PWD) electors, 80 years and above, COVID-19 suspect/positive.

d. Mandatory use of masks/sanitisers maintaining distance among the police personnel during training. Imparting training in small batches in big rooms.

e. The handling of the Electronic Voting Machine (EVM) and Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) during different stages of its preparation like First-level Checking (FLC), randomisation and Assembly Constituency-wise physical segregation, commissioning was done, following all COVID-19 norms like the use of gloves, sanitizing of the area, use of masks, placement of tables maintaining distance protocols.

f. Marking of 6 feet distance for a queue outside the polling station to maintain social distancing between voters.

-

g. Declaring all polling officials as frontline workers for getting them vaccinated against COVID-19. More than 85% of the polling personnel had been vaccinated to date. Moreover, vaccination was also done for all the officials, i.e., civil and police who are associated with the election process, in addition to the polling personnel.

-

h. Providing PPE (personal protective equipment) kits for facilitating voting by COVID-19 suspects/positives. This was facilitated between 6 to 7 p.m. in all the polling booths.

2. Followed only in a few polling booths

-

a. Mandatory use of masks, face shields, sanitizer, gloves by the polling personnel during the polling process.

-

b. Hand sanitizer to be provided for all voters before entry.

c. Checking of body temperature of all electors with the assistance of a handheld infrared thermometer by health workers. If any person has a temperature higher than the normal temperature, he/she will need to come in the last hour fixed for COVID-19 patients.

d. Use of disposable gloves for right hand-use of voters to push the button of the ballot unit of Electronic Voting Machine.

e. Disposal of gloves at the exit in bins and disposal of such bio-medical waste by an agency after the poll is over.

f. Sanitisation of polling stations.

g. Sector level health regulators for monitoring and supervision.

The Commission invoked Art. 324 powers and ordered the following, which was followed by the parties:

Post-election guidelines

The Commission settled counting of votes for General Election to Legislative Assemblies of West Bengal, Assam, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Puducherry along with bye-elections in various states on 2.05.2021. In view of the surge in COVID-19 cases throughout the country, the Commission had decided to make stringent provisions to be followed during the process of counting, in addition to existing Broad Guidelines dated 21st August 2021, and had directed that (Election Commission of India, 2020a, 2020b, 2021a, 2021b)

-

a. No victory procession after the counting on 2.05.2021 shall be permissible.

b. Not more than two persons shall be allowed to accompany the winning candidate or his/her authorized representative to receive the certificate of election from the Returning Officer concerned.

Bihar election

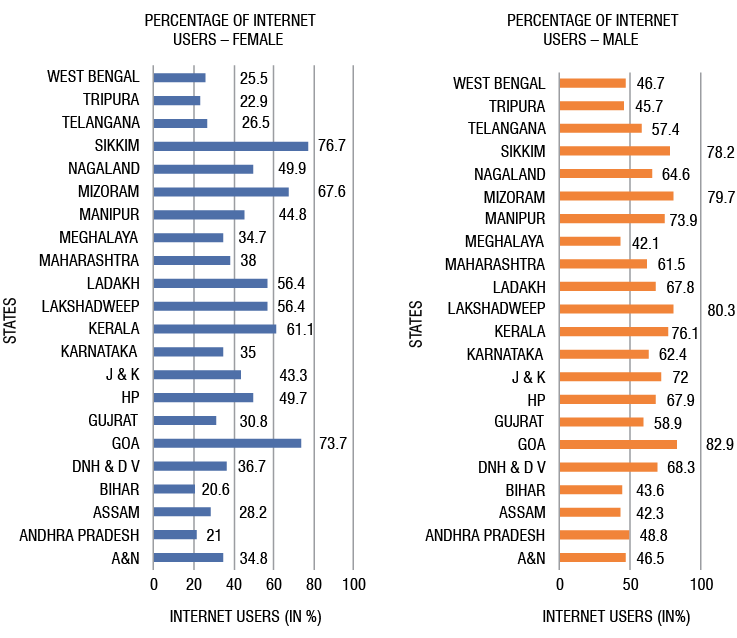

Bihar is a state with a total population (ORGCC, 2011) of 104,099,452 and is the third largest populous state of India with 243 constituencies. There were 6 national parties, 4 state parties, 7 state parties (other states), and 195 registered (unrecognised) parties apart from independent candidates contesting in Bihar. Over 70 million voters are eligible to cast their votes. As per the data provided by the Election Commission of India, Bihar has 72.9 million eligible voters this time around. In the 2015 elections, the state had 65,367 polling stations. The number now stands at 106,526, an increase of 62.96 per cent. 1,066 candidates are in the fray for the first phase of elections, 114 of them females (Mahesh, 2020). The Bihar election was held in three phases from October 28 to November 7 and the votes polled in the state assembly polls were counted on November 10. While Tamil Nadu and Kerala went to the polls in a single phase, there were three phases for Assam. West Bengal had assembly polls in eight phases.

The Election Commission of India rolled out the Broad Guidelines (Election Commission of India, 2021a, 2021b) for the conduct of general elections during COVID-19. There were two guidelines namely: (i) Pre-Election Guidelines and (ii) Post-Election Guidelines. This is applicable for all the states and with the outcomes of the Bihar election, the Election Commission of India also framed supplementary guidelines for the states and authorities to follow.

Figure 3. Vote percentage in Bihar

Source: own elaboration.

The majority of the voters voted for either the national party or the state party. The adherence to the COVID-19 guidelines by these two major campaign leaders would have set an example for the elections to follow. There was no spike in cases after the elections in Bihar, and therefore, less importance was given to the COVID- 19 guidelines by the subsequent campaigners. According to the Data Intelligence Unit (Prema, 2021), Bihar election dates were announced on September 25, when the total of confirmed cases in the state stood at 174,000. On the same day, the total number of COVID-19 recoveries stood at 160,000. When the first phase of the election took place on October 28, the total of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Bihar were 213,000, while recoveries were 203,000. When the second phase of the election took place on November 3, the state had 217,000 total confirmed COVID-19 cases, while there were 209,000 recoveries. When the third phase of the elections took place on November 7, total COVID-19 cases in the state stood at 220,000, while recoveries were 212,000. And finally, on the counting day, which was on November 10, Bihar’s coronavirus tally was 222,000, and the number of recoveries in the state was 215,000. The state surprisingly kept the cases in control, and the situation remained the same for the next couple of months until the second wave hit the nation.

West Bengal election

West Bengal has 294 assembly constituencies with a voter strength of 8.6 million. There are 12,068 polling stations facilitating the election. West Bengal went on an 8‑phase polling starting from March 27, April 1, April 6, April 10, April 17, April 22, April 26, and April 29, respectively. The Calcutta High Court, which is the highest court of the state, strictly warned that any person flouting the COVID-19 protocols must be taken to task (Prema, 2021).

After the elections at 1.7 per cent, Bengal had the third-highest COVID-19 fatality rate in India; the national average being 1.3 per cent. In terms of the test positivity rate (TPR), the state rapidly reached the seventh position in India. Bengal had a positivity rate of 6.5 per cent against the all-India average of 5.2 per cent (Sharma, 2021). Between January 15 and March 15, West Bengal reported about 14,000 COVID-19 cases and 269 deaths. However, between March 15 and April 19, the state reported over 89,700 cases and 371 deaths despite low testing. West Bengal conducted less than 46,000 tests per day between April 12 and 18. Further, between April 1 and 19, West Bengal reported a 13.62 per cent increase in total caseload with over 80,000 new cases (Singh, 2021).

The Election Commission had banned all victory processions in Assam, West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry on May 2, the day votes were to be counted. The processions are usually carried out by political parties to commemorate electoral wins. The ban was least followed by the supporters and there were mass gatherings and victory processions, as compared to the normal election.

Kerala election

With 33,406,061 inhabitants as per the 2011 Census. Kerala is the thirteenth-largest Indian state by population. Among the states, Delhi has registered the highest Internet penetration, while Kerala ranks second, according to a study by the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI). The virtual mode of campaigning was only used as a method to approach the younger generation, and the parties preferred rallies and door-to-door campaigns instead.

Kerala reported a jump of 31,000 cases and 197 deaths between March 1 and 15. Between the next 15 days, the state reported 35,000 cases and 225 deaths. Between April 1 and 19, Kerala reported 126,000 (an 11.18 per cent increase in the total caseload) COVID-19 cases and 318 deaths (Singh, 2021). The Kerala High Court, while deposing of a plea seeking imposition of full lockdown on the day of counting, noted that the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) – related safeguard measures adopted by the Election Commission of India and the state government for the counting day are sufficient, and ordered for the same to be strictly followed.

Officials on vote-counting duty in Kerala needed to either be fully vaccinated with both doses or carry a negative RT-PCR test report, not more than 72 hours old.

Tamil Nadu election

The Madras high court criticized the poll body as “the most irresponsible institution” for failing to implement proper COVID-19 guidelines during pre-poll campaigning. The high court bench comprising Chief Justice Sanjib Banerjee and Justice Senthilkumar Ramamoorthy held EC officials “singularly responsible” for the second wave of the coronavirus disease, with Chief Justice Banerjee even remarking that the election officials should probably be “accused of murder” (Bhaduri, 2021). Tamil Nadu reported about 8,000 cases and 50 deaths between March 1 and 15. That increased to 29,000 cases and 187 deaths between March 15 and April 1 – as the election campaigns were at the peak. Also, between April 1 and April 19, the state reported a jump of 113,000 cases (a 12.71 per cent increase in the total caseload) and 419 deaths (Singh, 2021).

Data from the Google transparency report, which covers political advertising on Google and YouTube partner websites, show that political parties and affiliated groups spent ₹466.1 million, totaling 19,071 ads, across the Google platform between February 19, 2019, and March 25, 2021 (Narayanan, 2021). Tamil Nadu is the highest spender on online political advertising in India. Tamil Nadu contributes the highest share at ₹1252 million or 27 per cent of the total ad spends in Google. Other poll-bound states such as West Bengal, Kerala, and Assam spent ₹285 million, ₹3.6 million, and ₹1.7 million, respectively. Facebook saw a total ad spend of ₹137.7 million on its platform across all the states between December 24, 2020, and March 23, 2021. West Bengal led the charge with ₹382 million followed by Tamil Nadu at ₹342 million. Poll-bound Assam and Kerala spent ₹6.5 million and ₹4.1 million, respectively, during this period (Narayanan, 2021). This might lure the first-time voters, but the rest of the voters are the major percentage to be covered, and the rallies played the role.

Assam election

As per the Census 2011, the total population of Assam is 312 million. The elections for the 126‑seated Assam Legislative Assembly were held in three phases between March 27 and April 6, 2021. Mass political rallies and roadshows were held in Assam like in other states (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2021; NFHS, 2021).

From the beginning of the pandemic until April 6, Assam reported 218,740 COVID-19 cases. On April 19, this number reached 225,822 – over 7,000 cases since April 6. During the same period, the state reported 33 deaths (Singh, 2021). In about a 40‑day period between February 8 and March 17, Assam reported 14 deaths and 643 cases. However, during the one-month period between March 17 and April 19, it reported 43 deaths and 7,950 cases. There was a steep increase in the confirmed cases from March till May 2021 (Table 3). While it is debatable whether the election contributed to the spread of the virus, the upward trend reveals that there are possibilities for that.

Table 3. Rise in COVID-19 confirmed cases between March 15 and May 26, 2021

Mar-15 Mar-31 Apr-15 Apr-30 May-10 May-15 May-26 West Bengal 251 982 6,769 17,411 19,445 19,511 16,225 Kerala 1,054 2,653 8,126 37,199 27,487 32,680 28,798 Tamil Nadu 836 2,579 7,987 18,692 28,978 33,658 33,764 Assam 20 49 499 3,197 5,803 5,347 5,699

Source: own elaboration.

COVID-19 outbreak after the elections

The difference in the trajectories of the COVID-19 outbreak in the election and non-election states lines up with the timing of the election process and provides evidence that election rallies contributed, at least in part, to the rapid rise in the number of cases in many states in India. The Election Commission of India started the process of notification of assembly elections in Assam, Kerala, Puducherry, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal in early March (on March 2 in West Bengal and Assam, and on March 12 in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry) (Basu, 2021).

Almost on a daily basis, these states then witnessed large gatherings of people in election rallies, without masks and without social distancing. This created a fertile ground for the rapid transmission of the virus across a wide section of the population. The trajectory of COVID-19 cases in these states reversed: from declining trajectories, we could see rising trajectories from early March (Basu, 2021). As the election rallies continued, the growth rate of average daily cases accelerated. The result was the explosion of cases that overwhelmed the healthcare system (Table 4). Once the surge in the number of cases emerged in the election states, it quickly overtook the average number of cases in the non-election states.

Table 4. Growth rate of the average daily number of COVID-19 cases (in percentage) (2021)

Since 1 st March Since 15 th March Since 1 st April Since 15 th April Non-election states 6.09 5.87 5.35 3.01 Election states 6.13 8.06 9.26 7.99 Assam 10.04 12.58 15.49 13.34 Kerala 4.99 7.72 10.8 9.47 Puducherry 7.94 7.86 6.97 6.11 Tamil Nadu 6.79 7.09 6.79 5.62 West Bengal 8.87 10.47 9.61 7.59

Source: own elaboration.

***

While the spread of COVID-19 depends on multiple factors such as total population and density, the most reliable indicator is the positivity rate. On that count, the biggest jump was seen by Delhi where it jumped from 0.4 per cent on February 26 to 31.8 per cent on April 28 (Deka, 2021). Though there was no election held in Delhi during that period, one cannot ignore the fact that the capital city has a far higher population density, more than 11,000 persons per square kilometre, than any of the states compared here.

Though there are various arguments that the elections are not the sole reason for the sudden spike in the virus infections rate, the Election Commission could have taken more stringent actions and tried to have control over the parties. Each state has a state election commission, which facilitates an easier approach to the political parties of the state in a federal government set-up. The state Election Commission should have ensured a discussion meeting with all the political parties in the fray. An all-party meeting ensures a smooth understanding of the guidelines and enforcement in the field rather than keeping a distance from the parties. Parties should have consulted on the feasibility of online campaigning methods and their benefits to the campaigners and the society during the pandemic.

The Election Commission of India could have set up a grievance redressal mechanism wherein the voters can record online the details of the guidelines that are being flouted. This would have ensured the nodal officer to take cognizance of such issues on the day of polling. Parliamentary committees or election observers were not included as a third-party mechanism to control all the stakeholders from defying the guidelines. The Election Commission of India should have set-up war-rooms to be operational on the polling day to have an update on the violation of the COVID norms at the polling stations through phone calls.

The Bihar elections were efficiently handled, although it went through many phases. It was a wise decision by the government to follow the other countries and conduct the elections even during the pandemic. In a democratic country, free and fair elections is the bedrock, and the conduct of elections is a mandate for a free state to function effectively. The political parties contesting in the elections had discontent over the guidelines and defied certain rules. There were no other negative responses with regard to the conduct of the elections on the side the political parties. The most affected by the second wave were the candidates, supporters, and the voters, as many were infected and some even lost their lives. The Election Commission of India did its part by ensuring that the guidelines were in place, but the duty does not end with the drafting of the guidelines but with enforcement. Severe enforcement of the guidelines in the field would have preserved the health and safety of the voters. The government in power or the judiciary cannot interfere in the election process, and therefore, it was solely resting on the shoulders of the Election Commission. If the Broad Guidelines (Election Commission of India, 2020a, 2020b, 2021a, 2021b) and the Supplementary Guidelines were enforced strictly by the Election Commission of India and followed diligently by the parties, voters, and supporters, the blame of the COVID-19 rise on the elections could have been avoided.

References

Akamai (2014). Akamai’s First Quarter, 2014 State of the Internet Report. Cambridge, MA: Akamai.

Akamai (2017). Akamai’s First Quarter, 2017 State of the Internet Report. Cambridge, MA: Akamai.

Basu, D. (2021, May 2). Did Political Rallies Contribute to an Increase in COVID-19 Cases in India? The Wire. https://thewire.in/politics/election-rally-covid-19‑case-spike (accessed: 5.05.2021).

Bhaduri, A. (2021, April 27). Kerala high court discards plea seeking lockdown on counting day. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/elections/kerala-assembly-election/kerala-high-court-discards-plea-seeking-lockdown-on-counting-day-101619519979470.html (accessed: 5.05.2021).

Chakravarty, P. (1997). Democratic Government and Electoral Process. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers.

Chaudhuri, R. N. (1999). Election Laws and Practice in India. New Delhi: Orient Publishing Company.

Data Intelligence Unit (2021). Low masking compliance, large mass gatherings: Bihar still evades a Covid surge. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/diu/story/low-masking-compliance-large-mass-gatherings-bihar-still-evades-a-covid-surge-1746457–2020–12–03 (accessed: 2.02.2021).

Deka, K. (2021, April 29). Is the Election Commission responsible for the second wave of Covid cases? India Today. https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/newsindia/is-the-election-commission-responsible-for-the-second-wave-of-covid-cases/ar-BB1gbSqV (accessed: 5.05.2021).

Down to Earth (2021). Viral campaigns: COVID-19 norms openly flouted at political rallies in West Bengal amid surge. Down to Earth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/gallery/governance/viral-campaigns-covid-19‑norms-openly-flouted-at-political-rallies-in-west-bengal-amid-surge-76488 (accessed: 5.05.2021).

Election Commission of India (2020a). Ref. No. 52/2020/SDR/Vol. 1.

Election Commission of India (2020b). Ref. No. 52/2020/SDR/Vol. I/1278.

Election Commission of India (2021a). Broad Guidelines, No. 464/INST/2021/EPS.

Election Commission of India (2021b). Broad Guidelines. https://eci.gov.in/files/file/12167-broad-guidelines-for-conduct-of-general-electionbye-election-during-covid-19/ (accessed: 10.04.2021).

Election Commission of India (1994). Order No 3/8/94/JSII, dated 13 January 1994.

Election Commission of India (1997). Circular No 437/6/97‑PLN-III, dated 1 December 1997.

Election Commission of India (1998). Order No ECI/GE98/437MCS/98, dated 16 January 1998.

Gadkari, S. S. (1996). Electoral Reforms in India. New Delhi: Wheeler Publishing.

Hall, T. E., Quin Monson, J., Patterson, K. D. (2009). The human dimension of elections: How poll workers shape public confidence in elections. Political Research Quarterly, 62 (3): 507– 522. DOI: 10.1177/1065912908324870.

James, T. S., Alihodzic, S. (2020). When is it democratic to postpone an election? Elections during natural disasters, COVID-19, and emergency situations. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, 19 (3): 344–362. DOI: 10.1089/elj.2020.0642.

Kanhaiyalal Omar v. R. K. Trivedi, AIR 1986 SC 111 (1985) 4 SCC 628.

Kaushik, S. (1982). Elections in India its social basis. Calcutta: K. P. Bagchi and Co.

Mahesh, S. (2020, October 27). How Bihar is ensuring a ‘safe and secure’ election during COVID-19 pandemic. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/oct/27/how-bihar-is-ensuring-a-safe-and-secure-electionduring-covid-19‑pandemic-2215646.html (accessed: 5.05.2021).

McKinsey Global Institute (2019). Digital India. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/McKinsey%20Digital/Our%20Insights/Digital%20India%20Technoloy%20to%20transform%20a%20connected%20nation/MGI–Digital-India-Report-April-2019.pdf (accessed: 10.04.2021).

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2021). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. https://www.mohfw.gov.in (accessed: 10.04.2021).

Mohinder v. Chief Election Commissioner, AIR 1988 SC 851 (paras, 91, 114–51, 121): (1978) 1 SCC 405.

Narayanan, V. (2021, March 25). Tamil Nadu parties have deep pockets for online campaigns. The Hindu BusinessLine. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/national/tamil-nadu-parties-have-deep-pockets-for-online-campaigns/article34161534.ece (accessed: 5.05.2021).

NFHS (2021). National Family Health Survey, NFHS-5 (2019–20). https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/HealthandFamilyWelfarestatisticsinIndia201920.pdf (accessed: 10.04.2021).

Noise Pollution (Regulation and Control) Rules, 2000 under the Environment (Protection) Act (1986). India.

ORGCC (Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India) (2011). Census of India. https://censusindia.gov.in/2011‑Common/Archive.html (accessed: 5.05.2021).

Prema, R. (2021). Election Commission has totally failed to implement Covid guidelines, says Calcutta High Court. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/elections/west-bengal-assembly-polls-2021/story/election-commission-failed-implement-covid-guidelines-calcutta-high-court-1794072-2021-04-23 (accessed: 3.05.2021).

Rijhwani, M. D. (1996). Election Law, Practices and Procedure. Mumbai: Somaiya Publications.

Shakdar, S. L. (1992). The Law and Practice of Elections in India. New Delhi: National Publishing.

Sharma, S. (2021, April 13). Polls and Covid go hand-in hand in Bengal, state now has third highest fatality rate in India. India Today. https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/other/polls-and-covid-go-hand-in-hand-in-bengal-state-now-has-third-highest-fatality-rate-in-india/ar-BB1fAlgV (accessed: 5.05.2021).

Singh, S. (2020). No precautions or masks as campaign for Bihar elections gathers momentum. Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/elections/assembly-elections/bihar/no-precautions-or-masks-as-campaign-gathers-momentum/articleshow/78688932.cms?from=mdr (accessed: 29.04.2021).

Singh, N. (2021, April 20). Polls in Pandemic: Active Cases in Bengal, Kerala Double in a Week; Assam Sees 230% Jump. News18. https://www.news18.com/news/india/polls-in-pandemic-active-cases-in-bengal-kerala-double-in-a-week-assam-sees-230jump-3660545.html (accessed: 5.05.2021).

State Election Commission (2020). Kolkatta, Letter No. B-3-82/2020–3780.

The Hindu (2021a). Election Commission asks political parties to follow COVID-19 norms. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/election-commission-asks-political-parties-to-follow-covid-norms/article34285579.ece (accessed: 29.04.2021).

The Hindu (2021b), HC to hear plea on action against leaders for not wearing masks during polls. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/hc-to-hear-plea-on-action-against-leaders-for-not-wearing-masks-during-polls/article34265797.ece (accessed: 29.04.2021).

TRAI (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India) (2020). The Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators (April-June 2020). New Delhi: Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

V. S. Achuthanandan v. P. J. Francis, AIR 1999 SC 2044: (1999) 3 SCC 737.

Unless stated otherwise, all the materials are available under

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Some rights reserved to SGH Warsaw School of Economics.