Studia z Polityki Publicznej

ISSN: 2391-6389

eISSN: 2719-7131

Vol. 9, No. 3, 2022, 29–46

szpp.sgh.waw.pl

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2022.3.2

Alberto Bortolotti

Polytechnic University of Milan (Politecnico di Milano), Department of Architecture and Urban Studies, Milan, Italy, e-mail: alberto.bortolotti@polimi.it, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1457-4262

How is the urban governance changing in response to the pandemic? The case of Milan

Abstract

This article deals with the effects of COVID-19 on the urban governance of Milan. The author argues that, despite the changeable situation still ongoing, looking at the measures assumed in 2020, the Municipality of Milan took middle-term strategies and radical decisions for the design and the use of the city from a perspective of sustainable prosperity together with the pandemic management. According to the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy, several policies were adopted in order to decongest public areas through the enlargement of spaces and services. In particular, during that period, the administration planned new policies in order to empower urban flexibility, rhythms and times, diversified mobility, public and green spaces, infrastructures, cooperation, and inclusion. In conclusion, the author argues that the pandemic has redefined the urban prosperity of Milan in relation to the sustainable transition and the new social challenges determined by the global scenario.

Keywords: Milan, COVID-19, urban policies, urban governance, sustainability

JEL Classification Codes: R50, R52, R58

Jak zmienia się współzarządzanie miastem w związku z wybuchem pandemii? Przypadek Mediolanu

Streszczenie

Niniejszy artykuł dotyczy wpływu COVID-19 na współzarządzanie miastem Mediolan. Odnosząc się do działań podjętych w 2020 r., autor dowodzi, że gmina miejska Mediolan – pomimo wciąż zmieniającej się sytuacji – ustanowiła strategie średnioterminowe i podjęła radykalne decyzje dotyczące projektowania i korzystania z miasta w perspektywie zrównoważonego rozwoju przy jednoczesnym zarządzaniu pandemią. Zgodnie ze strategią adaptacyjną „Mediolan 2020” przyjęto kilka polityk publicznych w celu zmniejszenia obciążenia miejsc publicznych poprzez rozszerzenie przestrzeni i usług. W szczególności w okresie tym administracja zaplanowała nową politykę ukierunkowaną na wzmocnienie elastyczności miejskiej, rytmów i okresów życia publicznego, zróżnicowanej mobilności, przestrzeni publicznych i zielonych, infrastruktury, współpracy i włączenia społecznego. Podsumowując, autor stwierdza, że pandemia na nowo określiła dobrobyt miejski Mediolanu w odniesieniu do zrównoważonej transformacji i nowych wyzwań społecznych determinowanych scenariuszem globalnym.

Słowa kluczowe: Mediolan, COVID-19, polityka miejska, zarządzanie miastem, zrównoważony rozwój

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: R50, R52, R58

COVID-19 has caused unpredicted changes in cities worldwide. Because of the social crisis it has generated, in many cases the pandemic represented an occasion for experimenting with innovative governance solutions inside several urban communities. In Europe, many public administrations designed radical policies for the recovery phase in order to give a response to COVID-19, which would be also able to contain social conflicts. In particular, considering the increasing territorial fragility and the proportional reaction to socio-economic cleavages, the most effective proposals for tackling the pandemic properly have taken into account two aspects: new scenarios and recovery actions (Kim et al., 2020: 22). This article aims to highlight which are the main challenges for re-thinking the urban governance in response to the pandemic and to show Milan as a case study for addressing innovative urban policies. Thus, the main objective of this article is to show how the urban governance of international cities reacts to the COVID-19 crisis.

Firstly, in terms of the general overview of urban policies, it was necessary to re-imagine new instruments and ways of governance which may be able to involve and integrate several departments of the same administration. In this sense, COVID-19 has made visible all the lacks of a fragmented landscape governance, which produced deep inequalities among countries, regions, and cities (Tasan-Kok, 2021), mainly because of the worldwide adaptation of an economic model, where the financial market is the only meritocratic place for allocating resources without any territorial consideration (Modiano, 2012: 135).

Secondly, a key aspect for a future overview of financialization processes related to urban planning and policies will be deeply connected to the paradigm that the COVID-19 pandemic is defining, which may be able to generate a diverse kind of development not connected directly to the network of global cities and maybe even composed of regional assets. Although we will not assist to a “sunset” of globalized capitalism, the pandemic could probably trigger processes of de-globalization and even political and economic regionalization in urban realities not firmly anchored to the international business context, while “it seems possible the design of uncertain combinations between persistent global orientations and more or less marked forms of regionalization” (Bolocan Goldstein, 2020: 205).

In particular, housing, social infrastructures, and flexible planning tools represent three key sectors of the new urban agendas which public administrations have tackled parallel to the health services that were mainly managed by upper administrative levels. In terms of the housing issue, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear that neoliberal policies of the last decades together with economic austerity were not enough for providing accessible and comfortable residentials to all the urban populations. According to the concept of “emergency urbanism” (Robinson & Roy, 2016: 182), the conflict between state power and private property has determined an increase in inequalities connected to a condition of banishment of middle and poor classes. Thus, in this scenario, illegal occupations, referendums, or massive demonstrations have become crucial for encouraging the design of cohesion territorial policies at a large scale. Moreover, the globalization of capitalism in the real estate market, which has been increased up to 60% for investments (Barnes et al., 2016: 5), has caused relevant socio-economic problems in citizens’ monthly salary. For instance, in several global cities the working class spends more than 50% of its salary for rental fees and, in order to tackle the rental issue, politicians have made radical proposals such as the occupation of vacant hotels in California, the referendum against the violence of “liberal urbanism” in Berlin and the plan of new residential districts for social housing in Amsterdam. In Milan, the pandemic “has not only sustained, but even accelerated certain dynamics that were previously underway” (Pasqui, 2022: 42). In the compared analysis of residential and commercial buildings between March 2019 and March 2020, there was a drop of –55.4% and –59.3% (National Council of Notaries, 2020) and despite this decline in sales, the average prices (€ 5,700/square meters) actually increased by +1.8% (Pasqui, 2022: 42). In other words, during the so-called “Century of Cities” the pandemic calls mayors of the world for a renovated “radical pluralism” in order to make the city a “laboratory” for future territorial policies which are able to reconnect the social fragmentation (Secchi, 2017: 74). In this sense, Milan represents a significant case study for understanding which devices, methods, and processes could be used in order to pursue these objectives. Cities may become a “laboratory” for new urban experiences because urban areas represent the center of conflict again. In order to investigate the reasons for this renovated urban need, we should consider the combination of two categories: “absolute local” and the “right to the city.”

A radical urban agenda after the pandemic

Adriana Cavarero firstly theorized the concept of “absolute local” in order to demonstrate that politics is a relational space, thus, the crises of national states as we have known them corresponds to a depoliticization of our societies. This expression is closely related to a sort of tyranny of proximity that entire groups of citizens have lived in the last decades: a clear perception of capitalism without touching it. In fact, several social groups were excluded from the benefits of globalism parallel to the fall of state sovereignty. As Gabriele Pasqui (2005: 44) affirmed “it is precisely the territorial nature of political power that is solicited and put in check, that nature which represents the cornerstone of political legitimacy and sovereignty. The extraterritorial nature of globalization processes is both the deconstruction of the link between territoriality and power and the affirmation of new forms of ‘locality,’ oscillating between identity localism and the reconstruction of new forms of community.”

According to Cavarero (2001: 67), “globalization and localization, through the double movement of inclusion and exclusion, seem to work together for a definitive liquidation of the model of the state: one nullifying the territorial cartography of sovereignty, the other exalting the territorial roots of community identity.” In other words, in a condition of absence of a strong national territorial authority, globalization, as an extraterritorial and de-territorializing force, determined “the contextual and contingent onset of the local.” However, because of the pandemic and the related need for state empowerment, today what seems possible is the creation of a social scenario composed of new structured political models linked to the territory and to the representation of public interest with a renovated sense of community belonging.

Before the theorization of the “absolute local” concept, Henry Lefebvre studied the habitat of the city in a historical moment where consumerism in the capitalistic society becomes dominant. Mostly since the 1960s, in the Western world there has taken place a structural decomposition of spatial models deeply adherent to traditional social frameworks such as the European cities during the Counterreformation period or the Neoclassicism Enlightened. After that period, the fall of communist paradigm and the rise of liberalism worldwide created a deep fracture in urban models as well. In particular, strategies for planning urban development went into crisis. Nevertheless, according to Lefebvre (1968: 129): “the urban renovation strategy, which is itself reformist, becomes forcibly revolutionary not by force of circumstances but against established situations.” Thus, in this sense, only under the pressure of coordinated social groups, urban planning will be able to reconnect a public need beyond influential “decision centers.” Nevertheless, the need to connect urban plans to shared ideologies is about the creation of a vision of the city, which is able to appropriate time, space, and will, in other words demanding “the right to the city” as a necessity.

Empowering the ordinary urban living instead of extraordinary events and decisions delivered by enlightened international élites regards an enhancing of local populations both urban and rural and connecting the Lefebvre mindset to Cavarero’s theory on “absolute local,” which may become relative if the exclusive right to “live on the move” is shared by each social class, in other words if the “right to the city” becomes a common ground for the entire citizenship. However, because of the large increase of inequalities, especially after the subprime crisis (2007), the opportunity of living in several spaces (diverse cities and environmental contexts) became a privilege of medium-upper classes, and the COVID-19 pandemic could be a chance for starting a radical social transformation which is able to re-equilibrate rights and duties in Western great cities.

In conclusion, for at least three entire decades our paradigm was fully composed of neoliberal theories and ideals, so the “glorification of the businessman” and the praise to the “free market” became a state of mind of each new generation of citizens. Moreover, neoliberalism represented a huge renovation also in social control of power through all the democratic states of the world. Contrariwise to several past radical social changes such as the French or the Soviet Revolution, during the 1980s global economic élites took the power without the use of any army and this transition happened because of a huge investment in what is actually universally called “cultural hegemony” (Gramsci, 1951). Thus, a complex technique of surveillance, defined by a mix of spatial lines, screens and artificial environments, designed an undetermined dimension of power which appears more physical than previously (Foucault, 1975: 194). So, the difference of neoliberalism to many other ideologies is about the way of governance which makes everybody thinking like the economic élites, independently from their own social status. According to this consideration, global economic business did not need to establish its power on the world financial system through a “military financialization,” but only directing flows of money in a proper way, financing cultural and political institutions, and setting a popular mentality based on the glorification of the financial market.

This social paradigm produced deep conflicts which contributed to the question of radical change in Western societies. Despite the subprime crisis, neoliberalism kept its power, even if the international élites became richer, as the “elephant curve” demonstrated (Milanovic, 2016). However, COVID-19 imposed an important modification in the globalization through the reinforcement of regional economies on the one side and the reduction of people’s moves worldwide on the other side, problematizing and highlighting that capitalism in the 21st century has mainly to do with commerce and finance. Milan perfectly fits this picture because of its geostrategic role in Northern Italy and because of the increasing impact that all of these phenomena have, affecting the city (Bortolotti, 2020).

However, the pandemic empowered the role of national states accelerating a significant re-organization of the scales of interests, which consist in the theory of “rescaling” (Brenner, 2004: 211). In other words, because of the role of public service in the management of the emergency, COVID-19 changed the neoliberal paradigm into a more social one where the supremacy of states and public administrations is again crucial for defining public policies. So, the future processes of urban transformation will take into account a different kind of governance and this scenario will have immediate effects on the Milanese urban policies.

The COVID-19 scenario through state, region, and municipality and the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy

How did Milan react to the COVID-19 crisis? The health crisis hit massively the Milan metropolitan area since the beginning of the Italian lockdown. What is still well remembered is the slogan “Milan doesn’t stop” launched by Mayor Giuseppe Sala at the end of February in order to react to the economic collapse the city was tackling because of the international pandemic scenario. At the same time, when the Italian government established the national lockdown, several strategic sectors had a strong decrease in terms of development, mainly in manufacturing and construction fields and their related businesses such as the fashion industry, furniture design, and finance. In April 2020, the City of Milan proposed a long-term strategy called the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy (Comune di Milano, 2020), “in which it attempted to lay out a strategy for the city’s recovery following the health crisis, launching various immediate or planned actions for managing a ‘new normality’” (Pasqui, 2022: 43).

Considering urban infections and regional contexts, the Milanese urban system is strongly connected to the productivity of provinces which surround the city (Varese, Como, Lecco, and Bergamo) and, from this perspective, the international study conducted by the University of Bergamo accurately showed that there is a clear link between working commuting, inhabitants’ density, and coronavirus infections. According to this research, the initial contagion in Lodi and Bergamo is related to the working and scholar connections among these provinces (Casti et al., 2021), because of the percentage of commuting for students or workers to a Municipality that is not the residential one which, in many cases, is more than 40% of the entire provincial population.

In particular, the highest percentage of infections is located in the area between Milan and Brescia (the Bergamo, Lodi, Cremona provinces) which represent the two main urban polarities in the Lombardy Region. This “urban zipper” is the place where connections are highly intense also on the global level of economic interactions because the same area is one of the most productive parts of the entire country. Therefore, local consequences of the contagion show that economic dynamics have indirectly supported virus spreads and maybe this consideration can suggest the elaboration of regional-based economies of scale in the future settlements in Lombardy.

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have opened a debate on the development of rural areas since spring 2020. The rural and the urban dimension were questioned mostly for healthy aspects, but the post-pandemic scenario will definitely have to work through several territorial contexts and scales.

In fact, since the lockdown period, several Milanese urbanists proposed new visions for living and, specially, in order to establish alliance between Milan and the villages located in inner areas surrounding the city, which are actually mostly uninhabited and poorly connected. The need of a new paradigm suggested structural investments in marginalized territories in order to relaunch entirely the competitiveness of the country, even though this operation could hold several critical issues closely related to the divergence between national and regional governments.

Starting from the consideration that all anti-urban perspectives do not have solid foundations and cities will continue to attract people, resources, projects, and growth (Pasqui & Tondelli, 2020), the most difficult issue seems related to the link among private housing, urban functions, and public services, which previously appeared quite disconnected.

As pointed out above, in response to the COVID-19 emergency the Municipality of Milan elaborated the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy, a policy tool which aimed to establish a new vision for the city also involving its metropolitan area. Although this document does not have a defined deadline of fulfillment, it is still an innovative device for experimenting innovative urban policy approaches, as this article analyzes below. Partially based on the “15 minutes city” theory (Moreno, 2020), the administration had the objective to make each inhabitant in the condition to reach the most essential services in his or her neighborhood in a short time.

Even if the solutions proposed still hold a lack of radical decisions, the Municipality of Milan understood that the “COVID-19 city” is a polycentric city composed of several cores and these cores suggest a diversified perception of the urban dimension. Through this emergency, public urban actors agreed that Milan needs to be more inclusive; in this sense, during the last decade, a significant problem of the city was represented by the high access costs to housing, restaurants, cafes, free time, sport, etc. This administrative strategy tackles the inequality issue through the design of a new development platform, which tries to mitigate expulsive phenomena (Sassen, 2014). Despite the economic growth caused by international events and fairs (Dente & Busetti, 2018), on the one hand Milan became more competitive worldwide but, on the other hand, increased the distances of peripheries, suburbs, and rural areas from the city center. Moreover, this administrative strategy involves both risks and resilience aspects because if, on the one hand, it tackles the idea that public goods could be temporarily adapted to alternative functions, on the other hand there are several risks regarding the potential negative social effects of readily changing and re-changing the uses of public goods.

According to the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy (Comune di Milano, 2020: 1): “the purpose of this document is to develop a strategy for the so-called ‘Phase 2,’ which will be dominated by a radical change in the lifestyles of our residents and the reorganization of our cities due to the need for social distancing and other precautions related to the coronavirus. Economic implications and changes in lifestyles are being addressed on every institutional level, both national and international, and we believe that today more than ever, the city of Milan is and should be part of the debate.” In other words, the approach stated by this instrument regards the policy design of “operational proposals” in order to complement and implement the Milanese urban agenda and of mapping, tracking, and assessing people’s immunity.

The biggest challenge for Milan is about the organization of work in the COVID-19 era. The idea of keeping the remote and smart-work model made time shifting easier for several activities and professionals, mostly involving offices. The urban economic labor market was drastically damaged by lost revenues and ongoing operational costs (mortgage, rent, labor, taxes, etc.), so, with the reopening of commercial activities, public spaces, and social life, the Municipality of Milan favored several interventions: bureaucracy reduction in order to “promote private investments, to overcome the excess of procedures and documentation required from our bureaucratic system, guarantee respect for the rules, and avoid illegality” (Comune di Milano, 2020: 2); smart mobility connected to a new city’s schedule which aims to make Milan change its rhythm and decongest public transport during the rush hour; redefinition of the use of roads and public spaces in order to “increase non-polluting mobility (walking, cycling, soft mobility) and to develop areas that will allow commercial, recreational, cultural, and sporting developments, while respecting the appropriate physical distances” (Comune di Milano, 2020: 3); rediscovering the neighborhood dimension and the city within a walking distance of 15 minutes, with a particular attention to the isolated elderly, those who are most vulnerable to disease, children and teens, who have suffered from the isolation. In addition to these policies, the new vision of Milan was designed according to a path of sharing, which will improve the strategy on the basis of a broad dialogue through the administration and Milanese citizens.

Moreover, the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy was based on several pillars: governance, rights and inclusion, through an empowerment of participation of everyone who is part of the city’s social fabric (representatives, non-profit organizations, and stakeholders); economy, resources and values through the promotion and distribution of industrial services and innovative tools in trade, construction chain and culture; work and labor market with the definition of pacts among public administrations on several levels, the consolidation of remote working practices, monitoring of women’s return to work and the adoption of extraordinary security, screening, sanitation, and coordination with the health authorities; timeline, spaces, and services with a structural rethink of timelines, schedules and rhythms of the city in order to distribute better the demand for mobility over the course of the day (Comune di Milano, 2020: 6) and new distancing measures promoting a better management of leisure time and a different use of public space; sustainability and environmental transition for equality, decarbonization, re-naturalization through the promotion of energy, climate and emergency response actions, the improvement of air quality as a precautionary measure for health and wellness, the implementation of circular economy principles starting from the reduction of food waste and the development of shared sustainable mobility (including shared bicycles and electric scooters).

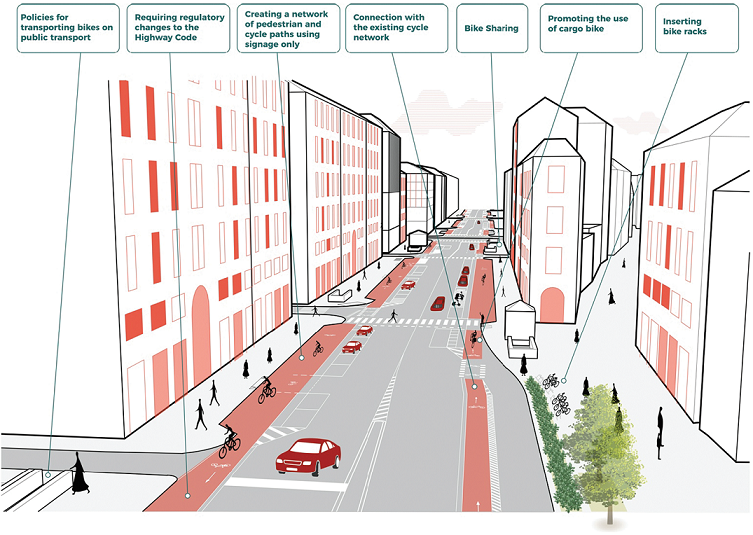

Figure 1. Buenos Aires Avenue intervention in the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy

Source: Comune di Milano (2020: 9).

In particular, the “Milano 2020” Adapation Strategy planned a group of “revitalization interventions,” which is composed of 6 main urban policies:

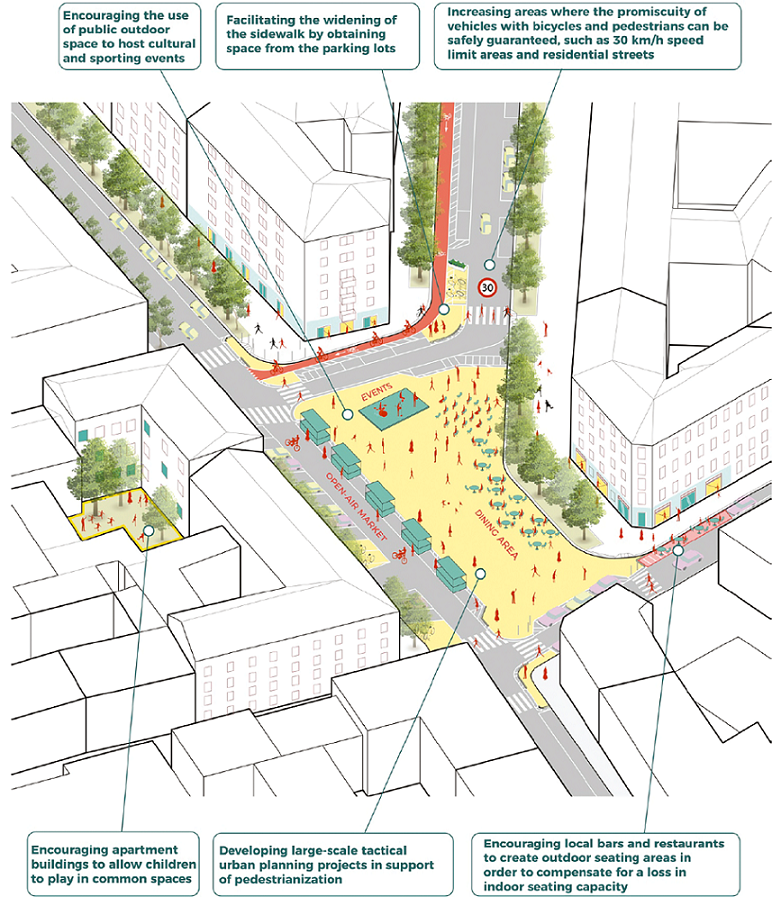

Figure 2. Minniti Square intervention in the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy

Source: Comune di Milano (2020: 11).

In conclusion, the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy defined a dynamic approach which is able to combine public policies to the new urban vision made of inclusion, cooperation, labor flexibility, shared and alternative mobility, circular economy, and public spaces. This strategy defined a generalized innovative sustainable paradigm, which may represent an alternative way of urban prosperity (Rifkin, 2013) compared to the so-called “Milano Model” political approach (Bortolotti, 2020). Even if Milan conserved its globalized projection despite the epidemic crisis because of its role in the C-40 network and the Winter Olympic Games Milan-Cortina 2026, the pandemic could trigger a radical change in the urban governance of the city. In particular, in spite of the incredible international development Milan has enjoyed during the last two decades (Taylor et al., 2007) and the rescaling process of state-nations and city-regions determinant for the competition among economic systems (Brenner, 2004), the pandemic could probably change the urban prosperity approach starting from sustainable criteria necessary for guaranteeing lower risk volatility of real estate assets. Thus, the parameters for determining a successful urban development in emerging world cities like Milan changed because of COVID-19 and the codification of the “Milano Model” approach will have a reverse way of mechanics because its modus operandi was deeply related to a vision of growth based on architectural spectacularization and expulsive phenomena. In other words, even if the policy framework of the “Milano Model” failed in delivering an exclusive way of prosperity, it could still represent the essential structure for a renovated geo-strategic approach, which actually also comprehends a general planning, sustainability, environment, informatic, real estate, and financial sectors in a spectrum of inclusive municipal collaborative community.

A social change for a sustainable change

The pandemic has challenged the principles of the free-market society and, in general, the foundations of the Western system by undermining the dominant neoliberal order. Therefore, the horizon that seems to be emerging is about a radical social transformation in which, within the maintenance of global interdependence linked to commercial, logistic, and financial value chains, alternative citizenship conditions can be built. Concepts such as those of a polycentric or flexible city, distributed become essential in the design of plans and policies capable of varying according to geographical, economic, and spatial contexts.

National states and public administrations were determinant in the pandemic management. According to Mariana Mazzuccato (2020: 7), “Governments should take an active role by shaping and creating markets that deliver sustainable and inclusive growth, as well as ensuring that partnerships with publicly funded businesses are driven by public interest and not profit,” so it is necessary that public bodies hold a major contractual power for addressing right decisions. This point has to deal both with administrative power and approach. Even if local administrations like the Municipality of Milan have a limited power, the pro-growth mentality did not look at the mayor and its council as a director-actor in urban processes but more as an activator or facilitator. Because of a new global mindset which put states in the center of the COVID-19 crisis management, this issue will closely become a key topic in the debate on the future of Milan. In particular, if, as it seems, governance policies are about business conditionalities for achieving incentives and investments, then also local administrations have to deal with a different approach to privatization and externalization of services and consultancies.

In fact, in terms of Milan, the key questions are: what city, for what population, and what opportunities? Because of this preamble, several urbanists and thinkers theorized new ways of living after the pandemic based on a real social change (AAVV, 2021), even if urban global phenomena for the recovery phase which will characterize Milan are still so far from urban dynamics in medium and small Italian towns. Beyond the scales, social rebalancing is always based on a different approach of urban governance, at the moment through the use of policy tools belonging to the “interstices” of public administration. Having a flexible approach, such as the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy has, means using “boundaries objects” (Balducci, 2011), in other words, designing urban policies which are structured by an integrated and coordinated system of little actions that, in the end, support the objectives stated in the main statutory plan vision.

People’s conditions were worse during all lockdown periods, so beginning with the design and implementation of social infrastructure could represent the starting point for empowering public and mixed-used spaces. Looking at libraries and schools as community centers means considering social infrastructure as territorial hubs for social innovation like what happened in Brussels through the “Contract école” instrument (Lamacchia et al., 2020: 242), where schools became centers of social life. These types of spaces can give dignity and opportunities to connect all social classes, emphasizing local networks and proximity.

As analyzed in the “Milano 2020” Adaptation Strategy, the tools of this flexibility, such as decongestion and decarbonization, the re-appropriation of public spaces endowed by the citizens as outdoor areas, and tactical urban planning or, in the most daring forms, terraces, tiers, and courtyards, can become important new principal spaces for social life.

In addition, the safeguarding of the previously discussed principle of the “right to the city,” if applied, will put mass tourism in crisis as we have known it, opening up alternative accommodation options also in hotels and accommodation facilities. As for office occupancy, although the value of towers and skyscrapers has remained substantially unchanged in Milan, smart working has gone up from 3%–4% to 30%– 40% of employees (Perulli, 2020), however, it will be necessary to understand if this trend will persist in a historical phase in which private entrepreneurship looks to the office as a place of social gathering of employees, as well as a place of work. In fact, the “Your Next Milano” event organized by Assolombarda and Milano & Partners at the end of 2020 showed that remote working in Milan was much more used than in the past, in data terms for 75% of industrial companies and business services firms in the city of Milan (as opposed to 43% before the crisis) and 54% in the metropolitan area (up from 20%) (Pasqui, 2022: 40).

With regard to an alternative use of offices, the decisions belonging to the conflictual context antithetical to gentrification that have been taken in cities such as Berlin seem more impactful (Vasudevan, 2021). In fact, although solutions for alternative temporary use of vacant private offices have been discussed for a long time, until a clear prerogative of the public actor in being able to lead co-management operations of the tertiary infrastructure is consolidated, it seems difficult to put in place an alternative urban policy in this decision-making area.

In other words, what the ongoing social transformation is going through is the implementation of a true urban and environmental sustainability which, in order to be implemented, requires a radical change of approach to the governance of the territory, the construction of a “thinking city” (Amin & Thrift, 2016). The pandemic represents an extraordinary opportunity to find a better balance between nature and society, through processes that favor reciprocity between the compact fabric of Milan and the system of farms, villages, small and medium-sized towns in the hinterland, a broader strategy capable of strengthening the circular economy based on kilometer agriculture as it is happening through the urban policies of Food Policy and ForestaMi.

Conclusion

As Richard Sennet (in the interview with G. Battiston, 2020) affirmed, “it is not easy to keep together contrast to ‘disease’ and adaptation to climate change: many of the recipes for dealing with climate change tend to make cities more compact, more crowded, more energy efficient but less healthy, while recipes to make them healthier often waste energy and tend in another direction. The pandemic invites us to think even more with an eye turned forward, aiming at what some call tactical urbanism and I call ‘open urbanism.’” So, the new urban issue connected to the concepts like sustainability or smart city, passes through a social environment much more porous, in contrast to the idea of a city controlled by machines, drones, or informatized systems.

However, the use of flexible policy tools which go into the direction of a new sustainable Milan made the “Milano 2020” Adaption Strategy a formidable instrument for deeply implementing a new urban vision based on the principle of decarbonization from a perspective of social justice which challenges Milan for being a recognized avantgarde city in the global scenario. If the city and its dynamics remain at the center of the rearrangements that intertwine global, regional and local, economic and political processes, then the perspective of Milan as an international hub for experimenting environmental sustainability and social justice and, at the same time, as a fulcrum city within a global city-region on the macro-regional scale, can become the pivot of a narrative that problematizes and resolves the debate of “Model Milan” as a starting point for designing a future important urban step.

On a final note, the case of Milan shows that the resilience of cities deals with local strategies and the relations that policies and actors design in order to shape and re-shape the continuous transition among crises. In this scenario, as Gabriele Pasqui (2022: 55) recently pointed out, “the market is simply not capable and has no intention of guaranteeing the provision of the kinds of public assets” but, in order to address equal policy approaches the need of a structured public sector for managing crisis is mandatory. So, the adaptation of cities and their capacity to tackle a world crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests that a different urbanity could be achieved only through urban policies that are mainly addressed by the state.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am alone responsible for this paper. This paper represents a focus of research related to my academic studies in urban policies. I hereby thank Professor Gabriele Pasqui for his scientific advice.

References

AAVV (2021). Milano siamo noi. Fuori dai luoghi comuni pensare una città autentica e democratica. Milano: Altraeconomia.

Amin, A., Thrift, N. (2016). Seeing like a city. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Balducci, A. (2011). Trading Zone” un concetto utile per alcuni dilemmi di pianificazione. Crios, 2: 38–45. DOI: 10.7373/70200

Barnes, Y., Tostevin, P., Tikhnenko, V. (2016). Around the world in dollars and cents. London: Savills World Research.

Bolocan Goldstein, M. (2020). Spazialità contese in una congiuntura critica. Ripensare il nesso tra città e territori. Pandora Rivista, 2: 204–209.

Bortolotti, A. (2020). “Modello Milano”? Una ricerca su alcune grandi trasformazioni urbane recenti. Santarcangelo di Romagna: Maggioli.

Brenner, N. (2004). New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casti, E., Adobati, F., Negri, I. (2021). Mapping the Epidemic: A Systemic Geography of Covid-19 in Italy. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cavarero, A. (2001). Il locale assoluto. Roma: Micromega Almalacco di Filosofia.

Comune di Milano (2020). Adaptation Strategy “Milano 2020”: Open document to the city’s contribution, https://www.comune.milano.it/documents/20126/7117896/Milano+2020.+Adaptation+strategy.pdf (accessed: 21.01.2022).

Dente, B., Busetti, S. (2018). EXPOst. Le conseguenze di un grande evento. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Foucault, M. (1975). Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison. Paris: Gallimard.

Gramsci, A. (1951). Quaderni del Carcere. Torino: Einaudi.

Kim, S. J., Matsumoto, T., Brooks, K., Romano, O., Alonso, E. E., Charles, L. (2020). Cities policy responses. OECD, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/cities-policy-responses-fd1053ff/ (accessed: 21.01.2022).

Lamacchia, M. R., Luisi, D., Mattioli, C., Pastore, R., Renzoni, C., Savoldi, P. (2020). Contratti di scuola: uno spazio per rafforzare le relazioni tra scuola, società e territorio. In: A. Coppola, M. Del Fabbro, A. Lanzani, G. Pessina, F. Zanfi, Ricomporre i divari. Progetti e politiche territoriali contro le disuguaglianze e per la transizione ecologica (pp. 239–250). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le droit à la ville. Sankt Augustin: Editions Anthropos.

Mazzuccato, M. (2020). Non sprechiamo questa crisi. Bari: Laterza.

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global Inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Modiano, P. (2012). Spunti per una riflessione sulla finanza milanese. In: M. Magatti, G. Sapelli, Progetto Milano. Idee e proposte per la città di domani. Milano: Mondadori.

Moreno, C. (2020). Droit de cité. De la “ville-monde” à la “ville du quarte d’heure”. Paris: L’Observatoire.

National Council of Notaries (2020). Annual index, https://www.notariato.it/it/news/l’impatto-dell’emergenza-covid-19-fase-1-sul-mercato-immobiliare-e-dei-mutui-il-notariato (accessed: 30.04.2022).

Pasqui, G. (2005). Progetto, Governo, Società. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Pasqui, G. (2022). Coping with the pandemic in Fragile Cities. Milano: PoliMI Springer.

Pasqui, G. Tondelli, J. (2020). Le città continueranno ad attrarre, liberiamo Milano da retorica e paura. Intervista a Gabriele Pasqui. Gli Stati Generali, https://www.glistatigenerali.com/milano/milano-gabriele-pasqui (accessed: 21.01.2022).

Perulli, P. (2020). Dove vivranno le classi creative, fulcro dell’economia dei Paesi avanzati? Dove vivranno i protagonisti del capitalismo immateriale? Uno schema interpretativo della grande crisi pandemica dovrebbe rispondere a queste domande. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Rifkin, J. (2013). The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power Is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Robinson, J., Roy, A. (2016). Debate on Global Urbanisms and the Nature of Urban Theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40 (1): 181–186. DOI: 10.1111/1468–2427.12272

Sassen, S. (2014). Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in Global Economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Secchi, B. (2017). La città dei ricchi e la città dei poveri. Bari: Laterza.

Sennet, R., Battiston, G. (2020). Immaginare strutture flessibile per un urbanesimo aperto. Intervista a Richard Sennet. CheFare, https://www.che-fare.com/battiston-sennett-strututre-flessibili-urbanesimo-aperto/ (accessed: 21.01.2022).

Tasan-Kok, T. (2021, March 7). Fragmented Governance Architecture of Contemporary Urban Development. Conference acts 18th IRS International Lecture on society and spaces, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-hQJtM2Z2c (accessed: 21.01.2022).

Taylor, O., Derudder, B., Saey, P., Witlox, F. (2007). Cities in globalization: Practices, policies and theories. London: Routledge.

Vasudevan, A. (2021). Berlin’s vote to take properties from big landlords could be a watershed moment. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/sep/29/berlin-vote-landlords-referendum-corporate (accessed: 21.01.2022).

Unless stated otherwise, all the materials are available under

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Some rights reserved to SGH Warsaw School of Economics.