Studia z Polityki Publicznej

ISSN: 2391-6389

eISSN: 2719-7131

Vol. 9, No. 2, 2022, 47-62

szpp.sgh.waw.pl

DOI: 10.33119/KSzPP/2022.2.3

Antonios Karvounis

Hellenic Republic Ministry of Interior; Hellenic Open University, Athens, Greece, e-mail: antonioskarvounis@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2682-6092

City diplomacy and public policy in the era of COVID-19: networked responses from the Greek Capital

Abstract

In recent decades, more and more young actors at the international level have been claiming and aspiring to play a significant role in managing public policy issues with global reach. The recent pandemic highlighted the asymmetry of nation-state responses in managing this health threat. At a time that the return-of-the-state scenario sounded familiar, it was misleading as well. Although each national government was focusing on its own people, and each claimed to have been better prepared to fight the crisis than its neighbors, governance gaps were filled by networks of sub-national authorities, whose partnerships provided a wider geographical perspective of policy decisions. In this framework, this article assesses the role of the city diplomacy, focusing on the pandemic initiatives of the city of Athens that, due to its international affiliations, managed to fill the gaps of the measures taken for the most vulnerable groups by the central government during the pandemic of COVID-19. Desk-based research and the use of secondary sources provide the scope for our analysis.

Keywords: city diplomacy, global governance, city networks, COVID-19

JEL Classification Codes: L38, Z18, Z28

Dyplomacja miejska i polityka publiczna w erze COVID- 19. Sieciowane reakcje z greckiej stolicy

Streszczenie

W ostatnich dziesięcioleciach coraz więcej nowych organizacji na szczeblu międzynarodowym aspiruje do odgrywania znaczącej roli w zarządzaniu kwestiami polityki publicznej o zasięgu globalnym. Niedawna pandemia uwypukliła różnice w reakcji państw narodowych w obliczu tego rodzaju zagrożenia zdrowia publicznego. To, że scenariusz powrotu inwestycji państwowych wydawał się możliwy, okazało się jednak mylące. Chociaż rządy wszystkich krajów koncentrowały się na własnych obywatelach, a politycy byli przekonani, że ich kraj jest lepiej przygotowany do walki z kryzysem niż sąsiedzi, luki w zarządzaniu musiały zostać wypełnione przez sieci władz niższego szczebla, których współpraca sprawiła, że decyzje polityczne miały szerszy zasięg geograficzny. W niniejszym artykule dokonano oceny roli dyplomacji miejskiej, koncentrując się na dotyczących pandemii inicjatywach miasta Ateny, które ze względu na swoje międzynarodowe powiązania zdołało uzupełnić braki w działaniach podejmowanych przez rząd centralny w czasie pandemii COVID-19 na rzecz grup najbardziej narażonych na jej negatywne skutki. Prezentowane badania bazują na analizie danych zastanych (desk research) i wykorzystaniu źródeł wtórnych.

Słowa kluczowe: dyplomacja miejska, współzarządzanie globalne, sieci miast, COVID-19

Kody klasyfikacji JEL: L38, Z18, Z28

Ivo H. Daalder, former United States ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (2009–13) has recently asserted that cities are playing a significant role in “addressing the many global challenges that our nations and others must confront – from climate change and cyber security to terrorism and pandemics…” (Dossani & Amiri, 2019). True, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the foreground the important role of cities in responding to global challenges. Cities, besides “getting things done” at the local level, are indispensable players in the global affairs, which commonly have traditionally been regarded as reserved for states. City leaders are networking across boundaries and driving the global pandemic response through informal and established international networks. Even while national collaboration was sometimes delayed or thwarted, city and municipal governments were among the first to look to their peers to exchange information, collaborate, and seek solutions. In fact, when it came to response to epidemics, the COVID-19 took central governments by surprise. The responses were often chaotic, even changing from day to day, lacking coordination (Rudakowska & Simon, 2020: 2). For instance, European national governments did not instruct their citizens whether or not to wear masks. In particular, initially in Germany, the Federal Ministry of Health on its website questioned the usefulness of wearing surgical masks, while on 15th April 2020, Chancellor Angela Merkel officially recommended wearing masks in public transport and while shopping and, finally, wearing masks became mandatory in Germany on 27th April 2020 (Rudakowska & Simon, 2020). In this respect, this patchwork of policies betrayed the fact that European governments were totally unprepared for such an emergency. Likewise in Greece, the national government’s measures were initially effective, as they managed to maintain a limited number of confirmed infections. Yet, the pandemic revealed certain gaps of the social protection system, as it appeared that the system was not ready to mitigate income insecurity and vulnerability.

On the other hand, local governments’ responses were more efficient than those of their national governments due to their formal and informal relations with well-known networks, such as C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, Metropolis, and United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) (Rudakowska & Simon, 2020: 3). In Greece, the international affiliations of the Capital enabled the municipality’s social services to respond effectively to the needs of the most vulnerable groups who were at most risk of contracting COVID-19. As one of 70 cities of the global Partnership for Healthy Cities, Athens took strategic actions, funded by the above-mentioned international network, to prioritize disenfranchised people who were vulnerable to the health and economic effects of the pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) applauded the city of Athens in promoting health equity and building a more just city (WHO, 2020). Likewise, the International Organization for Migration and the Cities Network for Integration provided the municipality with technical means to promote initiatives for host societies and refugee/migrant populations. Furthermore, as a member of the Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, Athens accelerated the digital transformation of its services.

In this sense, the goal of this article is to continue the debate about the role of city diplomacy in global affairs through the lens of a global pandemic. Despite the limitations concerning the capacity of the cities to address global challenges and the asymmetry in much of city diplomacy forms that part of the literature identifies (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020a: 604–606; Acuto et al., 2018; Bai, 2007; Burke-White, 2019), this article confirms that cities’ international actions are more pragmatic, quite innovative and, as a consequence, more efficient in a complex configuration of global order composed of states as well as other sites of authority such as global city networks (Curtis, 2016: 23). These are issues that will feature in the following discussion.

The article proceeds in five sections. The first section looks at the concept and tools of city diplomacy. The second seeks to explain how differently states and cities responded to COVID-19. The unilateral reaction of the states came in contrast to the multilateral initiatives of the local authorities, underlying the governance arrangements of which states and global city nodes are critical components. Then the third section turns to the Greek case, in which we examine the legal framework of the various forms of city diplomacy. And this brings us to the fourth section, the case study of the internationally inspired initiatives of the city of Athens during the pandemic of COVID-19. The short account of the municipality’s actions betrays novel forms of practices in global public policy making.

City diplomacy: the concept, tools, and motivations

Recent subject literature recognizes the international impact of cities and claims that the local governments are more efficient than their national counterparts and very often local governments are able to get things done, while states do not deliver (Hachigian & Pipa, 2020). Some have argued that cities, in opposition to the national governments, are predisposed to provide nimbler responses to some global concerns such as climate change or pandemics (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020a: 601). At the same time, as the world continues to urbanize at a rapid pace, cities are further poised to be front and center in the solution-seeking debates of future global challenges.

However, there are very few definitions of the concept of “city diplomacy.” In fact, the concept has never been seriously treated and described. Most of the definitions given to city diplomacy are functional, limited to the activities of cities. The definitions mainly come from specific organizations and international city associations active in promoting such actions. Specifically, in Recommendation No. 234 (2008), the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe defines city diplomacy as “a tool of local authorities and their associations to promote social cohesion, conflict prevention, conflict resolution, and post-conflict reconstruction in order to create a stable environment where citizens can live together in a state of peace, democracy and prosperity” (Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2008a: 3). In its decision No.251 (2008), the Congress argued that “city diplomacy expresses the growing importance of the city as a political actor at the international stage. Cities and their networks are involved in initiatives to build and consolidate peace in other areas” (Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2008b: 2). The Committee of the Regions (CoR) (2009: 3) maintained that “modern diplomacy is no longer expressed and practiced by national governments, given the need for dialogue, cooperation and coordination to achieve the objectives of peace, democracy, and respect for human rights in Europe. At all levels, closer cooperation between national governments and local and regional authorities is a natural but also necessary direction for a multilevel and more effective approach and strategy.” Indeed, the CoR (2009: 3) emphasized that “cities and major cities play an important role in international cooperation provided they cooperate with other municipalities in international networks.” Although the Federation of Canadian Municipalities did not define urban diplomacy in this way, it approached the international role of local authorities in terms of war and peace (Bush, 2003). These definitions are examples of extremely restrictive approaches to city diplomacy, focusing on security (conflict prevention, peacekeeping, post-conflict reconstruction actions), cooperation with developing countries, culture, and entrepreneurship.

On the other hand, the Netherlands Institute for International Relations identified six dimensions of urban diplomacy: security, development, economics, culture, networks, and representation (Van der Pluijm & Melissen, 2007: 19–33). As Van der Pluijm and Melissen argue (2007: 11), “city diplomacy can be defined as the institutions and processes by which cities engage in partnership with actors at the international political scene in order to represent themselves and their interests vis-à-vis others.” In this light, cities are not passive spaces suffering the indiscriminate exercise of top-down logics (Le Galès, 2002: 262). Indeed, cities play different roles in the international arena: as lobbyists exerting pressure on international organizations, while promoting and defending the interests and concerns of their residents; as mediators, negotiating agreements between local authorities; and as partners in projects, participating with other local authorities to promote or implement specific policies (Sizoo, 2007: 6–8).

The panorama of city diplomacy tools includes bilateral agreements (town-twinnings, cooperation agreements, memorandum of understanding), thematic/geographical/project-based city networks (e.g., UCLG, Eurocities, URBACT networks), ceremonial alliances (e.g., Olympic cities, European and African Capitals of Culture), and European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation. Most of the domestic legal framework allows cities to negotiate and implement a series of bilateral and multilateral agreements, formalizing partnerships with their foreign peers.

On balance, cities’ driving motivations for engaging in international affairs are regarded to be more solution-oriented and free of political considerations than those of national governments (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020a: 603). Learning about fresh and innovative ideas is possible through global involvement (Van Ewijk & Baud, 2009: 218–226; Johnson & Thomas, 2007: 39–48; Wilson & Johnson, 2007: 253–269), in order to attract investment and increase economic activity and to position and market the city’s brand and identity (Huggins, 2015: 129–215). Indeed, even in the most global cities, voters and constituents typically assess the performance of their locally elected officials and local government in terms of economic health and the efficient delivery of services such as public safety, waste management, transportation and mobility, utilities, parks and recreation facilities, education, and healthcare. Even when recognized to be vital components of local governance due to a city’s size or significance, foreign policy and international relations are rarely central to a mayor’s or local elected official’s campaign policy platform (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020a: 604).

Pandemic crisis: the failure of the nation-state or indication of the city diplomacy activism?

Countries’ initial reactions to COVID-19 were generally unilateral rather than international. They put geopolitical considerations ahead of globally coordinated solutions, turning inward and focused their policy responses on closing borders, stockpiling supplies, and enhancing their separate national reputations (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020a: 600). As a matter of fact, the COVID-19 coronavirus exhibited a lack of coordination between the European Union (EU) Member States, especially during the first wave of the pandemic, which caused confusion, deaths, as well as social and economic damage to the population. EU Member States began to take different approaches to confinement and population tests, as well as tests and different national measures restricting the free circulation of masks, medical and protective equipment, and unilaterally closing borders, posing a threat to the single market’s functioning and the principle of free movement of people (Rudakowska & Simon, 2020: 3). The Health Security Committee, an intergovernmental group that brings together Member States to establish a single strategy to respond to the crisis, was unable to reach a consensus on common measures, owing to a legal framework that allows Member States to take unilateral actions in an emergency (Beaussier & Cabane, 2021). In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the guidelines on the website did “not recommend” wearing a face mask, but on 3 rd April recommended wearing a cloth mask in public areas, not mentioning President Trump’s “mixed messages” on the issue (Bennett, 2020).

Cities and local governments, on the other hand, which were first in immediate policy responses, have been aggressive in leveraging their international relationships and networks to share experiences, coordinate local response and recovery plans, and develop a unified policy response to the COVID-19 crisis. On March 27, 2020, Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles organized a virtual meeting of 45 mayors of various cities to share their responses to COVID-19. The selected mayors come from C40 Cities, a global network of 96 of the world’s most populous cities dedicated to combating climate change. The C40 swiftly shifted its attention away from combating climate change and toward using its relationships, resources, and expertise with cities to help them lead on the front lines of the COVID-19 response. The United States Conference of Mayors conducted a critical study of communities and supported coordinated advocacy to Congress for COVID-19 extra emergency relief. The mayors of Buenos Aires, Bogotá, Lima, Madrid, Montevideo, and Santiago de Chile, who are all members of the Union of Ibero-American Capital Cities (UCCI), convened online to discuss their perspectives and strategies for dealing with the crisis. Many projects to promote local action, such as the UC LG’s Beyond the Outbreak platform, Metropolis, and the United Nations Human Settlement Program, have a worldwide scope (UN-Habitat) (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020b).

These are just some examples of the diverse global activity and collective action facilitated by city-to-city networks since the onset of COVID-19. These stand in stark contrast to the challenges experienced by the traditional, nation-state multilateral system in facilitating global cooperation to address the crisis. However, we must be very cautious not to misread the developments charted. The inability of traditional institutions to respond to the epidemic in a logical and timely manner fuelled the desire for speedy city-to-city collaboration (Pipa & Bouchet, 2020b). Yet, this is not a simple state failure with which we are faced. States now take their place in complex governance arrangements which city diplomacy influences and authority cannot be ignored (Curtis, 2016: 23).

In this sense, city diplomacy and experience exchanging among city personnel indicate a sort of global collaboration based on pragmatism and problem-solving rather than geopolitical objectives, distinguishing it from classic multilateralism of the international society of states. As Wang and Amiri have rightly pointed out, city diplomacy initiatives are mainly built around functional purposes as opposed to policy-oriented (Wang & Amiri, 2019). The disruption caused by the pandemic of COVID-19 presented an opportunity for local authorities to demonstrate their problem-solving role, accelerating their international affiliations and collaborations. The Greek case testifies how a municipality (i.e., Athens) can fill the gaps of the national social policies during the pandemic, making bolder use of its international affiliations.

The state of city diplomacy in Greece

The Greek local government has a long history of international cooperation, especially on town-twinnings (since the 1940s). Yet, the legal provisions for city diplomacy had not been formally codified before 2006. Indeed, the Communal and Municipal Code (L.3463/2006) set an advanced framework for the international partnerships of local government. In particular, it allows municipalities to conclude town-twinning agreements, sign other agreements/protocols on issues of common interest with their foreign partners, participate and establish international city networks and European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation, participate in European programs and initiatives of the EU and the Council of Europe, as well as in cultural exchanges and sports events.

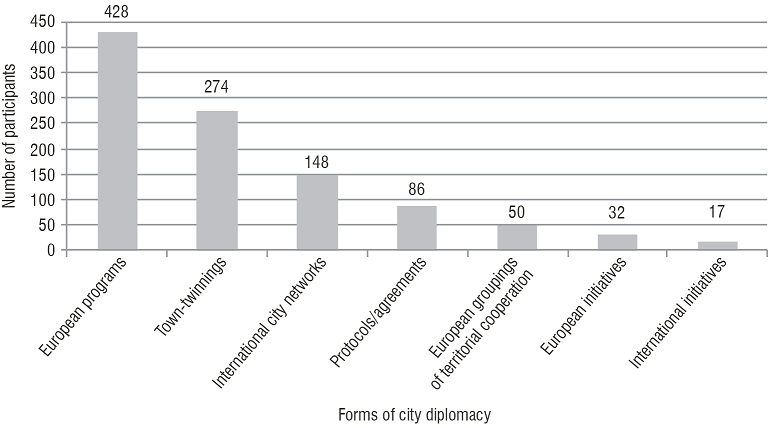

Figure 1. The approved Greek municipalities’ membership of city diplomacy forms, 2006–2020

Source: own elaboration of the database of the approved International Partnerships of the Greek Local Authorities from the Hellenic Republic Ministry of Interior (2021).

The law also provides that municipalities should receive the assent of the interministerial committee before the conclusion of the above-mentioned city diplomacy forms (see Figure 1). The approval of the committee is granted as long as the international activities of the municipalities are in line with their competences, the national policies, the national and EU law and the country’s international obligations. Furthermore, the committee acts as a space for dialogue between local authorities and the central government and aims to improve the coordination of the international initiatives that are being developed by the local government.

On the grounds of their approved international partnerships, besides sharing information, good practices, experience, and advice on how to deal with COVID-19, some Greek municipalities have been cooperating with their foreign peers on social policy and on issues such as medical equipment procurement, donation of masks, or fundraising for relief packages (Karvounis, 2021). For instance, the municipality of Shanghai (China) has sent 20,000 masks to the municipality of Piraeus (Greece). Piraeus and Shanghai have been twin cities and amidst the pandemic their mayors exchanged letters of support and shared information. However, apart from “mask diplomacy,” the case of the international activities of the municipality of Athens stands out as the most representative example of how a networked Greek city can respond effectively to pandemics due to its international affiliations. According to the database of the Hellenic Republic Ministry of Interior, the municipality of Athens has been involved more actively in city diplomacy than any other local authority in Greece since 2006, engaging in some of the most vibrant international city networks (European Forum for Urban Security, Champion Mayors for inclusive Growth, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Learning Cities, European Social Network, European Coalition of Cities against Racism (ECCAR), Partnership for Healthy Cities, Compact of Mayors, Conference of the Parties (COP21), 100 Resilient Cities, CIVITAS, European Network of Cities and Regions for the Social Economy (REVES), World Federation of Tourist Cities, etc.). Inevitably, when the pandemic of COVID-19 broke out, the largest city of Greece, facing severe and multiple social problems after a decade of a multifaceted crisis, capitalized on the heritage of its international links to fill the gaps of the national policy, especially for its most vulnerable residents.

Athens’ response in alliance with the Partnership of Healthy Cities

On February 26, 2020, Greece confirmed its first case of COVID-19, and the Greek government implemented social distancing measures to stem the spread of the coronavirus. It declared a near-total lockdown in early March 2020, along with the shutdown of all educational institutions and non-essential enterprises. Greece was able to maintain a low number of confirmed illnesses as a result of these timely actions. The administration began gradually relaxing the confinement measures on April 28, 2020. However, in November 2020, the government decided to implement a second lockdown in order to prevent an outbreak of illnesses (Konstantinidou et al., 2021: 5). Indeed, during the first (March 2020) and second (November 2020) lockdowns, a variety of initiatives was implemented to reduce the consequences and assist residents in maintaining their income. Strengthening the healthcare system (infrastructure and staff capacity) was prioritized in order to respond to the pandemic’s ever-increasing needs, as well as retaining employment and compensating employees’ earnings. Moreover, the administration decided to prolong unemployment and social security benefits, provide economic assistance to particular groups of the population, and delay tax payments. Measures were also taken to guarantee that employees and self-employed persons were not infected, as well as to make it easier for working parents to fulfil their responsibilities (Konstantinidou et al., 2021). However, the COVID-19 shock made the need to continue modernizing Greece’s social protection system manifest so as to target better anti-poverty programs to people in need and strengthen significantly retraining schemes (OECD, 2020: 9).

The pandemic exposed some flaws in Greece’s social protection system, as it appeared that the system had not yet built effective procedures to avoid and reduce economic insecurity and vulnerability. Although the above-mentioned income-compensation methods were projected to mitigate the negative effect on incomes to some extent, there were still considerable obstacles. These steps did not cover everyone, and no specific measures to help certain vulnerable groups (disabled individuals, migrants and refugees, single-parent families, large families, Roma people) cope with the COVID-19 problem were implemented. As a result, there were significant gaps in support for dealing with the socioeconomic implications of the pandemic, particularly for the most vulnerable sections of the population (Konstantinidou et al., 2021; OECD, 2020). Most of the support measures were temporary income support measures taken as a response to the crisis. They mostly dealt with tweaking existing social protection measures and were not expected to result in significant changes that would transform the system. Furthermore, economic instability and resulting massive job losses were predicted to exacerbate the already high unemployment rate, while drops in disposable incomes were expected to result in a major increase in the number of persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the coming years (Konstantinidou et al., 2021).

Bearing in mind these developments, in order to protect marginalized populations, the city of Athens worked rapidly to bring together specialists from various sectors. They were well aware that these severe policy choices would have a significant negative impact on vulnerable groups, who would be isolated, have treatment and rehabilitation services disrupted, and have less access to social programs. Due to the greater incidence of noncommunicable diseases, these groups were also at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 and developing more severe cases (NCDs). Furthermore, due to food store closures, the pandemic has intensified food insecurity for these populations (WHO, 2020). “These very harsh times have taught us that the best outcome always comes with collaboration,” the Mayor of Athens, Mr Bakoyannis, asserted (WHO, 2020). In reality, Athens is one of 70 cities that make up the Partnership for Healthy Cities, a global network dedicated to saving lives through the prevention of NCDs and injuries. This initiative, which is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies and implemented in collaboration with the World Health Organization and Vital Strategies, enables cities throughout the world to implement high-impact policy or programmatic interventions to reduce NCDs and injuries in their communities. The network’s scope has been broadened to help local responses to the COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020, recognizing the critical role of cities in executing national policies and tackling issues on the ground. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Athens city officials worked with the Hellenic Liver Patients Association “Prometheus,” the Greek Association of People Living with HIV “Positive Voice,” and received funding from the Partnership for Healthy Cities to improve support for getting essential supplies and health information to marginalized communities (WHO, 2020). During the pandemic, qualified personnel and volunteers delivered necessary items including food, water, gloves, masks, and antiseptic solutions to those who were homeless, intravenous drug users, sex workers, and migrants three days a week in Athens and Thessaloniki. From March through June, about 7,000 food and drink packages, 250 pieces of protective equipment, and 400 safe injection kits were distributed to over 4,650 service users. Existing inequalities and structural injustices were revealed and exacerbated by the outbreak of the coronavirus. Shelters for homeless Athenians and those battling with drug addiction were established to address these inequities and those at danger, giving protection and medical assistance. Moreover, during the lockdown, a system called Health at Home Plus was set up to bring food, medicine, and aid to the homes of tens of thousands of citizens. The system has continued to provide services and meet the demands of the population until today (Hoecklin, 2020).

The Versatile Center for Homeless People mixes housing with health and social assistance to improve participants’ physical and mental well-being. Residents can also use the day service, which includes personal hygiene facilities, a healthy supper, and internet access, as well as a resting area. In April, Athens built a second, more specialized facility for drug users. The facility provides temporary housing as well as drug treatment and recovery programs. Cities must build on the pandemic’s triumphs and innovation to catalyze progress toward safeguarding everyone’s right to health. “The WHO supports Athens with advocacy and evidence-based policy guidance for COVID-19 and beyond” – emphasized Ms Marianna Trias, the WHO representative for Greece (WHO, 2020).

Furthermore, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) have been supporting the activities of the Cities Network for Integration on a trilateral basis with the city of Athens since April 2020. The two international organizations have supplied necessary technical means to build systems and procedures that support initiatives with long-term benefits for both host communities and refugee/migrant populations, based on the objectives set by the participating towns. Since December 2018, the IOM has been funding the CNI as part of its “Durable Solutions” program. The Athens Coordination Center for Migrant and Refugee Issues (ACCMR), through its digital service mapping platform, and the International Rescue Committee Hellas (IRC), through its Refugee.Info platform, have teamed up to make information exchange and access to services for migrants and refugees in Athens easier. Furthermore, one of challenges of the pandemic was the necessity to speed up the digital transformation of services in order to make them more accessible. The city has made significant strides in digitizing its public services and continues to place a high value on these initiatives. The city of Athens, as a member of the Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, has launched projects like the Athens Digital Lab to integrate innovation and more digital solutions that will help the municipality run more efficiently (Krinis, 2021).

The Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, which was founded in November 2018 by the cities of Amsterdam, Barcelona, and New York and now has a membership of over 50 cities around the world, is a network of cities assisting each other in the greenfield of digital rights-based policymaking. The Coalition is dedicated to promoting and defending digital rights in urban settings through local action, as well as working toward legal, ethical, and operational frameworks to advance human rights in digital contexts. The Cities Coalition for Digital Rights is a group of cities dedicated to using technology to improve people’s lives and assist communities in cities by providing reliable and secure digital services and infrastructure.

Finally, the municipality of Athens has a number of plans for the Greek Capital in the post-COVID-19 era, including attracting digital nomads, hosting the first Innovation Summit, welcoming international film productions, renovating more public spaces, and strengthening its collaboration with international networks to develop the city’s tourism potential (Krinis, 2021).

The city of Athens collaborates with the World Tourism Organization, the World Organization of Conferences and Exhibitions (ICCA), and the World Meeting Organizations on a regular basis to achieve these objectives (Meetings Professionals International). According to Ms Melina Daskalakis, president of the Athens Development and Destination Management Agency (ADDMA), the municipality of Athens is developing a Sustainable Tourism Observatory that will be an important tool for collecting and analyzing data on the tourism economy. Athens will be allowed to join the International Network of Sustainable Tourism Observatories (INSTO) of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and will finally be represented in world rankings and publications with correct scientific data. This will aid the municipality’s competitiveness in worldwide markets, as well as its ability to connect with its partners at the local level. “We are continuing to enhance our connection with worldwide networks, exchanging expertise and best practices that will help us develop our potential,” Ms Daskalakis explains (Krinis, 2021). In reality, as part of its objective to establish sustainable tourism practices, the city of Athens has begun working toward a relationship with the World Tourism Association for Culture and Heritage (WTACH).

Most recently, Athens has become a destination member of the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), and according to Ms Daskalakis, Athens is collaborating with the GSTC team on a “destination evaluation” so that “we have a better picture of the evolution of Athens as a sustainable tourism destination” (Krinis 2021).

***

In this article, our concern has been to take a concrete phenomenon – city diplomacy – and to exhibit, in particular, its implications over a global challenge – the pandemic of COVID-19. Then, we went on to examine the responses given by the internationally minded cities along with those given by the traditional nation-state multilateral system. Cities seemed to understand better than central governments that global problems necessitate global responses and collaboration. Does that mean a shift from a form of order based upon the international society of states to a form of order where state no longer plays a central role? As Curtis (2016: 2) rightly points out, what is critical is that such transnational urban networks are not simply a challenge to the state. This is not a zero-sum game, where the rise of cities necessarily means the decline of states. As the case study of the municipality of Athens has exhibited, cities can use their international affiliations in situations of emergency when, at the same time, the national governments take measures horizontally that hurt the most vulnerable members of the society. When addressing global issues such as climate change or pandemics, cities propose a different public policy-making process, joining together with city networks to solve the issues upon which national governments are slow to act. It seems a logical corollary that states will constructively collaborate with and consider further empowering cities to cooperate and share best practices amongst municipal counterparts so as to lead effective responses to global problems.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Research Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Ministry of Interior, Hellenic Republic (2021). The Approved International Partnerships of the Greek Local Authorities, https://www.ypes.gr/politikes-kai-draseis/diethni-kai-europaika-program-mata-ota/nomiko-plaisio-diethnous-drasis-ota/apofaseis-epitropis

References

Acuto, M., Decramer, H., Kerr, J., Klaus, I., Tabory, S., & Toly, N. (2018). Toward City Diplomacy: Assessing Capacity in Select Global Cities. Chicago Council on Global Affairs, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/toward_city_diplomacy_report_180207.pdf (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Bai, X. (2007). Integrating Global Concerns into Urban Management: The Scale and the Readiness Arguments. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 11 (2): 15–29.

Beaussier, A.-L., & Cabane, L. (2021). Improving the EU Response to Pandemics: Key Lessons from Other Crisis Management Domains, https://www.e-ir.info/2021/01/28/improving-the-eu-response-to-pandemics-key-lessons-from-other-crisis-management-domains/ (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Bennett, B. (2020, Apr 3). President Trump Says Americans Should Cover Their Mouths in Public – But He Won’t. Time, https://time.com/5815615/trump-coronavirus-mixed-messaging/ (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Burke-White, W. (2019). At Climate Summits, the Urgency from the Streets Must Be Brought to the Negotiating Table. Brookings Planet Policy blog, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/planetpolicy/2019/12/16/at-climate-summits-the-ur-gency-from-the-streets-must-be-brought-to-the-negotiating-table/ (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Bush, K., (2003). Building Capacity for Peace and Unity: The Role of Local Governments in Peacebuilding. Ottawa: Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

Committee of Regions (2009). City Diplomacy. Opinion. 78th Plenary Session, 12–13 February. Brussels: Committee of Regions.

Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (2008a). City Diplomacy. Recommendation, 234. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (2008b). City Diplomacy. Resolution, 251. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Curtis, S. (2016). Cities and Global Governance: State Failure or a New Global Order?. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, I (3): 455–477.

Dossani, R., & Amiri, S., (2019). City Diplomacy Has Been on the Rise: Policies Are Finally Catching Up. Rand Corporation Official HomLe Page, https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/11/city-diplomacy-has-been-on-the-rise-policies-are-finally.html (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Hachigian, N., & Pipa, A. F. (2020). Can Cities Fix a Post-Pandemic World Order? Foreign Policy, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/05/cities-post-pandemic-world-order-multilateralism/ (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Hoecklin, M. (2020). Cities on the Forefront of COVID-19 Response – Experiences From Athens, Bogota and Kampala. Health Policy Watch, https://healthpolicy-watch.news/cities-health-Covid-athens-bogota-kampala/ (accessed: 12.10.2021).

Huggins, C. (2015). Local government transnational networking in Europe: a study of 14 local authorities in England and France. PhD Thesis. Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth.

Johnson, H., & Thomas, A. (2007). Individual Learning and Building Organisational Capacity for Development. Public Administration and Development, 26 (1): 39–48.

Karvounis, Α. (2021). Paradiplomacy and social cohesion: The case of the participation of the Greek municipalities in European city networks. Social Cohesion and Development, 15 (1): 81–95.

Konstantinidou, D., Capella, A., & Economou, C. (2021). Social protection and inclusion policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis: Greece. Brussels: European Commission.

Krinis, N. (2021). Interview: ADDMA’s Melina Daskalakis Reveals Athens’ post-Covid Plans for Tourism, https://news.gtp.gr/2021/07/06/interview-addmas-melina-daskalakis-reveals-athens-post-Covid-plans-for-tourism/ (accessed: 14.10.2021).

Le Galès, P. (2002). European cities, social conflicts and governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ministry of Interior, Hellenic Republic (2021). The Approved International Partnerships of the Greek Local Authorities, https://www.ypes.gr/politikes-kai-draseis/diethni-kai-europaika-program-mata-ota/nomiko-plaisio-diethnous-drasis-ota/apofaseis-epitropis (accessed: 25.10.2021).

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2020). Economic Surveys: Greece 2020. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pipa, A. F., & Bouchet, M. (2020a). Multilateralism Restored? City Diplomacy in the COVID-19 Era. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 15: 599–610.

Pipa, A. F., & Bouchet, M. (2020b, Aug 6). How to make the most of city diplomacy in the COVID-19 era. Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/08/06/how-to-make-the-most-of-city-diplomacy-in-the-covid-19-era/ (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Rudakowska, A., & Simon, C. (2020, Sept 1–14). International City Cooperation in the Fight Against Covid-19: Behind the Scenes Security Providers. Global Policy, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/articles/health-and-social-policy/international-city-cooperation-fight-against-covid-19-behind (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Sizoo A. (2007). City Diplomacy. Concept Paper. Hague: VNG.

Van der Pluijm R., & Melissen, J. (2007). City Diplomacy: The Expanding Role of Cities in International Politics. The Hague: Clingendael Institute.

Van Ewijk, E., & Baud, I. S. A. (2009). Partnerships between Dutch municipalities and municipalities in countries of migration to the Netherlands; knowledge exchange and mutuality. Habitat International, 33 (2): 218–226.

Wang, J., & Amiri, S. (2019). Building a Robust Capacity Framework for U. S. City Diplomacy. Los Angeles, CA: USC Centre on Public Diplomacy.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2020). Care and guidance for marginalised populations during the COVID-19 pandemic: Athens, https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/athens-protects-vulnerable-communities-during-covid-19 (accessed: 15.10.2021).

Wilson, G., & Johnson, H. (2007). Knowledge, Learning and Practice in North-South Practitioner-Practitioner Municipal Partnerships. Local Government Studies, 33 (2): 253–269.

Unless stated otherwise, all the materials are available under

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Some rights reserved to SGH Warsaw School of Economics.