1(5)2015

Izabela Zawiślińska

Open Government Partnership

as a new global intergovernmental initiative

Abstract

Arising with a higher frequency economic crises over the last decades coupled with the deteriorating situation in the public finances have not always been caused by wrong decisions taken by the public authorities or their mismanagement. The crises of confidence in financial institutions in numerous countries combined with crises of confidence in the state spur to look for new solutions in the public institutions management and their relationship with the national and international environment. The concept of open government (OGP) fits into this trend. It is, in a sense, a new, although for some countries only a modernized way of organizing activities and institutions in a state that uses digital technology and communication tools in order to increase the participation of citizens in governance at all levels and decision-making. In addition, it is assumed that the knowledge and involvement of citizens can be used to effectively solve problems both at central and local levels. In the article the author tries to explicitly point out that while the Open Government Partnership initiative should be assessed positively, it cannot be regarded as a panacea for contemporary problems in management of the state and communication with the public. The mere membership does not guarantee to streamline the procedures, mechanisms, institutions and society involvement in public life. These specific actions aimed at increasing transparency, efficiency and cooperation as well as participation of citizens are an indicator of change. And these can be undertaken within the framework of the Partnership, as well as outside of it.

Keywords: open government partnership, public governance, civil society participation, new technologies.

Partnerstwo Otwartego Rządu jako nowa inicjatywa międzyrządowa

Streszczenie

Pojawiające się z coraz większą częstotliwością w ostatnich dziesięcioleciach kryzysy gospodarcze połączone z pogarszającą się sytuacją w sferze finansów publicznych nie zawsze powodowane są błędnymi decyzjami władz publicznych czy ich niegospodarnością. Kryzysy zaufania do instytucji finansowych, połączone w wielu państwach z kryzysami zaufania do państwa, skłaniają do poszukiwania nowych rozwiązań w sferze zarządzania instytucjami publicznymi oraz ich relacji z otoczeniem krajowym i międzynarodowym.

W ten nurt wpisuje się koncepcja otwartego rządu (OGP). Jest to w pewnym sensie nowy, choć w wypadku niektórych państw jedynie zmodernizowany, sposób organizacji działań oraz samych instytucji w państwie, wykorzystujący cyfrowe narzędzia technologiczne i komunikacyjne w celu zwiększenia współudziału obywateli w rządzeniu na wszystkich szczeblach sprawowania władzy i podejmowania decyzji. Ponadto zakłada się, że wiedza i zaangażowanie obywateli mogą posłużyć do skuteczniejszego rozwiązywania problemów zarówno na szczeblu centralnym, jak i lokalnym.

W artykule Autorka stara się wyraźnie podkreślić, że o ile sama inicjatywa Partnerstwa Otwartego Rządu powinna być oceniana pozytywnie, to nie można jej traktować jako panaceum na współczesne problemy w zarządzaniu państwem i komunikacji ze społeczeństwem. Samo członkostwo nie stanowi gwarancji usprawnienia procedur, mechanizmów i instytucji oraz zaangażowania społeczeństwa w życie publiczne. To konkretne działania ukierunkowane na wzrost przejrzystości, efektywności oraz współpracy i partycypacji obywateli stanowią wyznacznik zmian. A te mogą być podejmowane w ramach Partnerstwa, jak również poza nim.

Słowa kluczowe: partnerstwo otwartego rządu, współzarządzanie publiczne, partycypacja społeczna, nowe technologie.

The Open Government Partnership – OGP – is a voluntary global initiative that aims to secure concrete commitments from governments to their citizenry to promote transparency, empower citizens, fight corruption, and harness new technologies to strengthen governance and improve their effectiveness. In pursuit of these goals, OGP provides an international platform for dialogue and sharing among governments, civil society organizations, and the private sector, all of which contribute to a common pursuit of open government. OGP stakeholders include participating governments as well as civil society and private sector entities that support the principles and mission of OGP1.

The concept was shaped by a series of consultations in early 2011 between the founding governments and civil society organizations from around the world. OGP formally launched on September 20, 2011 in New York City when eight founding governments (Brazil, Indonesia, Philippines, Mexico, Norway, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States) formally adopted the Open Government Declaration and announced their first OGP National Action Plans. Since then, the partnership has grown to 65 countries, representing a third of the world’s population. Participating governments have made over 1,000 commitments to be more open and accountable to their citizens. With two successful annual summits in Brasilia and London, ongoing implementation and monitoring of more than 50 national action plans, and a vibrant network of civil society and government reformers, OGP try to establish itself as an influential global movement towards more open and responsive government2.

Vision, mission, goals and principles of OGP

The main OGP’s vision is that more governments become sustainably more transparent, more accountable, and more responsive to their own citizens, with the ultimate goal of improving the quality of governance, as well as the quality of services that citizens receive. This will require a shift in norms and culture to ensure genuine dialogue and collaboration between governments and civil society.

In the mission the main point is that the OGP provides an international platform to connect, empower and encourage domestic reformers committed to transforming the government and society trough openness. It also introduces a domestic policy mechanism – the action planning process – through which the government and civil society are encouraged to establish an ongoing dialogue on the design, implementation and monitoring of open government reforms.

OGP aspires to support both government and civil society reformers by elevating open government to the highest levels of political discourse, providing ‘cover’ for difficult reforms, and creating a supportive community of like-minded reformers from countries around the world. The key objective of OGP for next years is to make sure that a real change is happening on the ground in a majority of OGP countries, and that citizens are benefiting from this change. There are three primary ways for OGP to help make sure the right conditions are in place for countries to deliver ambitious open government reforms: maintain high-level political leadership and commitment to OGP within participating countries, support domestic reformers with technical expertise and inspiration and foster more engagement in OGP by a diverse group of citizens and civil society organizations. In addition, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) seeks to ensure that countries are held accountable for making progress toward achieving their OGP commitments3.

There are four main OGP principles. First of them is transparency. Information on government activities and decisions should be open, comprehensive, timely and freely available to the public, and must meet basic open data standards. The second principle is accountability. It means that rules, regulations, and mechanisms are in place that call upon government actors to justify their actions, act upon criticisms or requirements made of them and accept responsibility for failure to perform. Citizen participation is another principle of Open Government Partnership. In accordance with it, the government seeks to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to more responsive and effective governance. The subsequent principle applies technology and innovation. Governments embrace the importance of new technologies in driving innovation, providing citizens with open access to technology, and increasing their capacity to use technology4.

Requirements

To join OGP, countries must first and foremost meet the eligibility criteria and embrace the Open Government Declaration. In minimum eligibility criteria governments must exhibit a demonstrated commitment to an open government in four key areas, as measured by objective indicators and validated by independent experts. The areas are:

•Fiscal transparency – which means publishing on time essential budget documents in transparency forms,

•Access to information – through an access information law that guarantees the public’s right to information,

•Income and asset disclosure – rules that require public disclosure of income and assets for elected and senior public officials,

•Citizen engagement – the participation in policymaking and governance.5

To join OGP, countries must also commit to upholding the principles of an open and transparent government by endorsing the Open Government Declaration. Through endorsing this Declaration, countries pledge to “foster a global culture of open government that empowers and delivers for citizens, and advances the ideals of open and participatory 21st century government”6.

After signing the Declaration the next required step is to prepare an OGP action plan. Each participating country must develop an OGP National Action Plan (NAP) through a multi-stakeholder, open, and participatory process. The action plan contains concrete and measurable commitments undertaken by the participating government to drive innovative reforms in the areas of transparency, accountability, and citizen engagement. Moreover OGP participating countries commit to developing their national action plans through dialogue and the active engagement of citizens and civil society. Countries agree to develop their country commitments according to the following principles:

•availability of timeline,

•adequate notice,

•awareness raising Countries to enhance public participation in the consultation,

•multiple channels: Countries must consult through a variety of mechanisms – including online and through in-person meetings – to ensure the accessibility of opportunities for citizens,

•breadth of consultation: Countries must consult widely with the national community, including civil society and the private sector,

•documentation and feedback: the summary of the public consultation and individual written comment should be made and be available online if possible.

Countries must report on their consultation efforts as part of the Self-Assessment Reports. The Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) will also examine the application of these principles in practice. Upon finalization, countries are expected to submit the action plan to the OGP Support Unit and upload it directly to the OGP website7.

It might however be emphasized that governments should begin their OGP national action plans by sharing existing efforts related to their chosen grand challenge (s), including specific open government strategies and ongoing programs. Action plans should then set out governments’ OGP commitments, which stretch government practice beyond its current baseline with respect to the relevant grand challenge. These commitments may build on existing efforts, identify new steps to complete ongoing reforms, or initiate action in an entirely new area. Commitments in country action plans should be ambitious in nature. An ambitious commitment is defined as one that, once completed, will show a demonstrable advancement from action plan to action plan in the grand challenge areas proposed by OGP through openness, transparency, civic participation, and accountability. In the context of pre-existing commitments, ambition is defined as expediting the time frame for completion of the stated goals of a commitment. OGP recognizes that all countries start from different baselines. Countries are charged with selecting the grand challenges and related concrete commitments that most relate to their unique country contexts. No action plan, standard, or specific commitments are to be forced on any country8.

The next requirement concerns the implementation of the OGP commitments in accordance with the action plan timeline. OGP participating countries operate on a two-year action plan cycle, in which there are no gaps between the end of the last action plan and the beginning of the new one. This means every country will be implementing a NAP at all times. In order to achieve this, countries will draft their new action plans during the last six months of implementation of the previous NAP. All NAPs should cover a period of implementation of a minimum of 18 months, although individual commitments may vary in length.

During implementation, countries are encouraged to take advantage of the technical resources and knowledge sharing opportunities that come with participating in this international initiative, such as the OGP Working Groups and participating countries who have made a pledge to support their peers. OGP countries should contact the OGP Support Unit to identify and connect with networks of peer governments, multilateral institutions, and civil society organizations for assistance with technical expertise or resources needed to implement their commitments. During the implementation of action plans countries must conduct public consultations. Having a platform for permanent dialogue can help build trust and understanding and provide a forum to exchange expertise and monitor progress.

Moreover countries are obliged to prepare yearly self-assessment reports. During the two-year action plan cycle, governments are required to submit two annual Self-Assessment Reports to assess the government’s performance in living up to its OGP commitments in its action plan. The Self-Assessment Report should provide an honest evaluation of the government performance in implementing its OGP commitments, based on the timelines and benchmarks included in the country’s OGP action plan. The two Self-Assessment Reports will have similar content to one another, differing primarily in the time period covered. The Midterm Self-Assessment, due following the first year of implementation, should focus on the development of the NAP, consultation process, relevance and ambitiousness of the commitments, and progress to date. The End of Term Self-Assessment, due at the end of the two-year implementation period, should focus on the final results of the reforms completed in the NAP, consultation during implementation, and lessons learned. The development of the Self-Assessment Reports must include a two-week public consultation period as stipulated in OGP Guidelines. The governments are obliged to keep their self-assessment reports brief and jargon-free so that they are understandable to a broad audience. Self-assessment reports must be published both domestically and on the OGP website9.

Subsequent requirement applies to participation in Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM). The mechanism delivers biannual reports for each OGP participating country. These progress reports assess countries on the development and implementation of their OGP action plans and offer technical recommendations to help improve future action plans. Moreover governments are also expected to contribute to the advancement of an open government in other countries by sharing of best practices, expertise, technical assistance, technologies and resources, as appropriate using the various peer exchange and knowledge sharing mechanisms made available by OGP10.

Membership and organizational structure

OGP participating countries are organized into cohorts based on when they joined the Initiative. Thus, at their creation the level of economic development, geographical location or size of the state are not taken into account. It allows to keep groups of countries on the same calendar and creates opportunities for peer exchange. After joining, countries are required to follow their cohort’s timeline for implementing an action plan, assessing their own progress, supporting an independent progress report – according to independent reporting mechanism – and developing further action plans.

Regardless of when a government of a country submits its letter of intent, the country will be asked to finalize and post its first OGP action plan by March 31st of the following year. It therefore encouraged countries to submit their letter of intent and begin drafting their action plans by November of the calendar year, as it can take to 4 months to develop an ambitious action plan with sufficient opportunities for public. Currently we have four cohorts. The founding 8 countries formed cohort 1 when they joined OGP in September 2011, the 39 countries that joined this Initiative in April 2012 comprise cohort 2, the 7 countries that joined in April 2013 comprise cohort 3 and 11 countries that joined as the last in 2014 comprise cohort 411.

The OGP initiative is led by a Steering Committee (SC). It is the executive, decision making body of the OGP. The main role of the SC is to develop, promote and safeguard the values, principles and interests of OGP. It also establishes the core ideas, policies, and rules of the partnership, and oversees the functioning of the partnership. As an executive body and through its subcommittees, the Steering Committee does the following:

•provides leadership by example for OGP in terms of domestic commitments, action plan progress, participation in the Biannual Summit, and other international opportunities to promote open government,

•sets the agenda and direction of OGP, with principled commitment to the founding nature and goals of the initiative,

•manages stakeholder membership, including eligibility and participation,

•conducts ongoing outreach with both governments and civil society organizations,

•provides intellectual and financial support, including through in-kind and human resource support,

•sets and secures the OGP budget12.

The Steering Committee is comprised of the government and civil society representatives that together guide the ongoing development and direction of OGP, maintaining the highest standards for the initiative and ensuring long-term sustainability. The Committee can consist of up to 22 Members (11 representatives from OGP participating governments and 11 civil society representatives), with parity maintained between the two constituencies. OGP uses the United Nations Statistical Division regional breakdowns for the government Steering Committee election of new government members. A minimum of 1 and maximum of 4 governments can serve on the Steering Committee from each region at any one time (Africa, Asia, the Americas and Europe as defined by the United Nations Statistical Division). Each OGP participating government votes to elect new government Steering Committee representatives each year. The civil society chairs will install a selection committee to organize the rotation of civil society representatives.

Members of Steering Committee are chosen to four years and maximum for two consecutive terms. In 2014, the first time that government members will rotate, there will be a special election in which governments will join for staggered one, two, and three year terms to ensure regular annual rotation from 2015 onwards. The Steering Committee will transition each year on October 1. Both the outgoing and incoming members should be invited to attend the first SC meeting following the election of new members13.

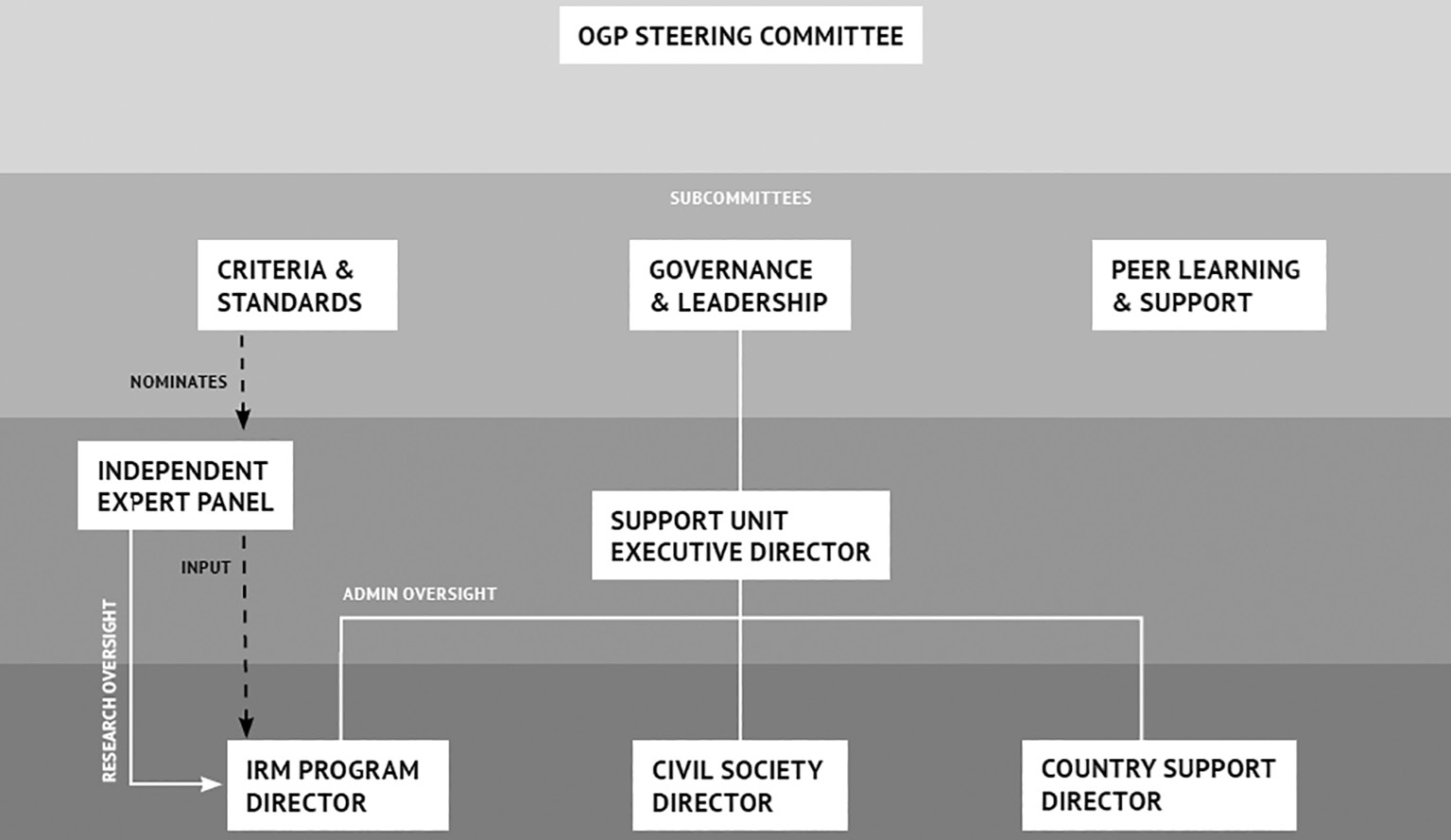

Figure 1. OGP Governance Structure

Source: Open Government Partnership, Four-Year Strategy 2015–2018, p. 37, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Steering Committee Chairs comprised of four members elected by the entire Committee. It includes a lead government chair, a support (or incoming) government chair, and two civil society chairs. The SC chairs are responsible for:

•Leadership: Safeguard the values and spirit of OGP, including the strategic collaboration and balance between civil society and governments and the vertical accountability of OGP between a government and its citizens. This includes overseeing and ensuring necessary resources for the Support Unit,

•Outreach: This includes leading in the initial set-up of multilateral partnerships and being the entity that enters into contractual relationships on behalf of OGP,

•Representation: The lead chair speaks on behalf of OGP as a whole at key forums and with media,

•Coordination: The Governance and Leadership Subcommittee, which is made up of the four chairs, is to hold regular consultations in between OGP meetings to coordinate country outreach efforts, plan meetings, and otherwise further the interests of OGP.14

The Steering Committee has three standing subcommittees to support its work. Subcommittees are charged with carrying out preliminary work to inform decisions taken by the entire SC. Subcommittees make recommendations to the full SC for decision. The SC may be comprised of equal numbers of the government and civil society representatives drawn from the larger SC. The standing subcommittees are as follows:

The Governance and Leadership Subcommittee (GL) serves as the executive committee, comprising of the four OGP chairs. It ensures continuous management of OGP, making decisions and keeping processes moving in a timely manner,

The Criteria and Standards Subcommittee (CS) recommends to the SC the eligibility criteria for OGP governments and indicates to SC when there may be a need to update the criteria. It makes recommendations to SC when the government’s actions are deemed contrary to OGP principles and its full participation in OGP is in question. It develops guidelines for government self-assessment reports and other best practices. It maintains a watching brief over the IRM to ensure that the International Expert Panel (IEP), project management team, and local researchers are able to deliver high quality and accurate reports,

The Peer Learning and Support Subcommittee (PLS) oversees OGP’s strategy for country support and peer learning, in particular on promoting peer exchanges across OGP countries. Key mechanisms for peer exchange include OGP regional events, webinars, and thematic working groups, as well as resource materials to be shared on the OGP website15.

OGP is supported by a small permanent secretariat – The Support Unit. It provides a secretariat function for all participating countries and has the following responsibilities: maintaining institutional contacts and memory, managing brand and communications, and ensuring the continuity of organizational relationships with core OGP institutional partners and donors. The Support Unit serves as a neutral, third-party between governments and civil society organizations, ensuring that OGP maintains the productive balance between the two constituencies. The Support Unit keeps records of all OGP documents. It is also responsible for managing the master list of OGP stakeholders and their contact information. The Support Unit manages all external communications for OGP, working closely with the GL when questions arise. In addition, the Support Unit will assume responsibility for providing targeted support to OGP participating governments to help connect them with the expertise, resources, and technology they need to develop and implement their OGP commitments. This may include, inter alia, partnering with the private sector, civil society, academics, governments, and others to develop tools and frameworks to assist OGP participating countries in developing and implementing innovative and effective open government commitments16.

Reporting Mechanism

Action plans should be for a duration of two years, although individual commitments contained in these action plans may be for more or less than two years, depending on the nature of the commitment. However, each action plan should include one-year and two-year benchmarks, so that governments, civil society organizations, and the Independent Reporting Mechanism, have a common set of time-bound metrics to assess progress. As living documents, action plans may be updated as needed based on ongoing consultations with civil society. Any updates must be duly noted in the official version of the action plan on the OGP website.

Furthermore all OGP participating governments are to publish a midterm self-assessment report at most three months after the end of the first year of the action plan implementation. This report should follow OGP guidelines in assessing the government’s performance in meeting its OGP commitments, according to the substance and timelines set out in its national action plan. This report should be made publicly available in the local language (s) and in English. It should be also published on the OGP website. An end of term self-assessment report will be required after two years of the action plan implementation.

However, the monitoring of the implementation of the action plan does not end with the above procedure reporting. A new reporting mechanism – Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) was approved by the OGP Steering Committee at its September 2014 meeting in New York. An independent progress report is to be written by well-respected governance researchers, preferably from each OGP participating country. These researchers are to use a common OGP independent progress report instrument and guidelines, based on a combination of interviews with local OGP stakeholders as well as a desk-based analysis. This report is to be shared with a small International Experts Panel for peer review to ensure that the highest standards of research and due diligence have been applied. The draft report is then shared with the relevant OGP government for comment. After receiving comments on the draft report from each government, the researcher and the International Experts Panel finalize the independent progress report for publication on the OGP portal. OGP participating governments may also issue a formal public response to the independent report on the OGP portal once it is published.

The IRM is overseen by an International Expert Panel (IEP) that is nominated through an open process and selected by the OGP Steering Committee. The IEP is comprised of up to 10 experts representing a diversity of regions and thematic expertise – 5 members with a steering role and 5 with a supporting, quality control role to rotate over the cycle of their terms. These technical and policy experts are appointed by the OGP Steering Committee following a public nominations process.

The IRM is led by the full-time IRM Program Director, to be supported with adequate staff. All such positions are housed within the Support Unit for administrative and fiduciary reasons, but the report to the IEP, in terms of content, is to ensure independence of thought and appearance. The IRM Program Director will not have a reporting relationship to the Criteria and Standards Subcommittee, but will maintain a strong working relationship with members to keep the Steering Committee informed of progress. The Executive Director does not sign off on the content of any individual IRM report17.

Early results and strategic objectives

OGP’s first three years have surpassed most expectations for what an initiative like this could achieve in such a short amount of time and with such a minimal investment of financial resources. For example OGP provided the impetus for a number of governments to finally enact politically difficult – but extremely important – policy reforms, for which civil society had been advocating for years. In Brazil, Croatia and Georgia, the OGP action planning process has led to passage of new right to information laws. In Ghana, the Cabinet approved a right to information bill that had been pending for a long time, and in Indonesia, the OGP commitment pushed the Ministry of Home Affairs to monitor implementation of existing right to information laws at the local level. Moreover many countries have seen improvements in their public procurement process. These include publishing all contracts (in Hungary) and making this information more easily available via common website (in Romania). In Peru and Liberia, the government is working with civil society to develop the content and format of public procurement data to be presented via their websites18.

Moreover, total, 958 commitments were made in the first year of OGP. Of the commitments evaluated, 270 (29%) were completed. This number is expected to increase, as many additional commitments are on track to be completed in the next year, and the IRM only evaluated the first year of the two-year action plan cycle. For Cohort 2 countries (those that joined in 2012), the IRM evaluated the potential impact each of their 775 commitments would have in the relevant public policy area. Of those commitments, 188 (24%) were found to have potentially transformative impact. Of the 775 OGP commitments made be Cohort 2 countries, according to the IRM reports, 318 (41%) were new, meaning that those commitments were publicly announced for the first time in the OGP action plan.

Among the new commitments, nearly 32 percent had transformative potential impact, much higher than the overall average (19%) for all commitments. This suggests that when new initiatives are introduced as part of an OGP action plan, they may be relatively more ambitious than previous initiatives. The IRM assign stars to commitments that are clearly relevant to OGP values, have a substantial level of completion or higher (on track for complete), are specific enough to be measurable, and have a moderate or substantial impact. Of the 775 commitments evaluated for stars, 198 (almost 25%) of OGP commitments were starred by the IRM. The percentage of starred commitments ranges from 0 percent in some cases to over 50 percent in high-performing countries19.

The OGP eligibility criteria set a minimum baseline for countries to join, focusing on the areas of fiscal transparency, access to information, asset disclosure and civic participation. To be eligible to participate in OGP, countries are expected to score at least 75 percent of the total possible points available to them. In 2013, five countries took specific steps to improve their score in order to become eligible to join OGP:

•Sierra Leone passed a freedom of information law in October 2013 and announced they were joining OGP at the London summit,

•Tunisia released the Executive’s Budget Proposal late last year in order to improve their fiscal transparency score and meet OGP eligibility. Tunisia sent its letter of intent to join OGP in January 2014,

•Malawi released both the Executive’s Budget Proposal and Audit Report in order to improve their fiscal transparency score and meet OGP eligibility. Malawi sent its letter of intent to join OGP in July 2013,

•Senegal passed a sweeping Transparency Law in December 2012, which improved their score on a number of OGP’s eligibility criteria (although Senegal has not yet reached the minimum threshold),

•Shortly after the political transition in Myanmar, the government announced its intent to become eligible to join OGP by 2016. It is currently working to develop and implement the necessary reforms to meet the eligibility score. Last September Myanmar took an important step in passing an anti-corruption law (replacing the previous code from 1948),

•Kosovo conducted its own independent review of the government’s performance on OGP’s eligibility criteria in order to make the case for joining OGP and then sent its letter of intent in June 201320.

Following a start-up phase of rapid growth (2011–2014), the OGP Steering Committee has agreed that in its next phase of consolidation (2015–2018), OGP’s key objective is to make sure that real change is happening on the ground in a majority of OGP countries and that citizens are benefiting from this change. Therefore, the focus should be on achieving four strategic objectives. These are:

•maintain high-level political leadership and commitment to OGP (top-down),

•support and empower government reformers with technical expertise and inspiration (mid-level),

•foster more engagement in OGP by a diverse group of civil society actors (bottom-up),

•ensure that participating countries are held accountable for making progress toward achieving their OGP commitments21.

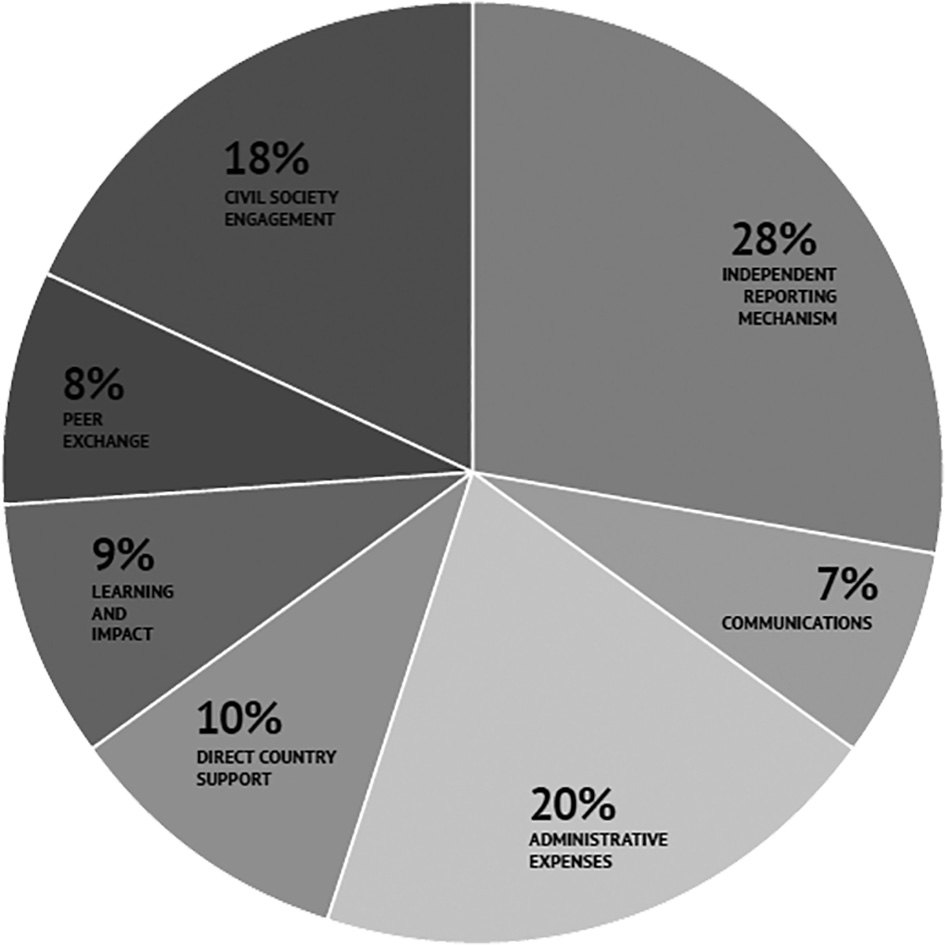

To advance its strategic objectives, OGP has six core program components led by the OGP Support Unit and the Independent Reporting Mechanism: Direct Country Support, Civil Society Engagement, Peer Exchange, Learning and Impact, Independent Reporting, and External Communications.

The goal of the first core program is to build relationships with the points of contact and keep them informed about OGP requirements, timelines and events, while also gathering information about progress, delays, requests for multilateral support, and any other local developments that might affect OGP implementation. The ultimate objective of the Direct Country Support program is to improve the quality of both the design and implementation of OGP action plans. Experience of the past year indicates that targeted interventions at the right stage of the cycle can help ensure that action plans include more ambitious, relevant commitments that are structured in a way that makes assessment easier and promotes accountability. The Direct Country Support program also provides guidance and models for establishing an ongoing dialogue with civil society partners. Once action plans are completed and the implementation phase begins, the Support Unit will continue to work with countries to help overcome hurdles as they arise. When external expertise or financial resources are needed, the team works to broker additional support from OGP’s multilateral partners and/o OGP working groups.

Figure 2. 2015 Projected Budget Distributed By Program

Source: Open Government Partnership, Four-Year Strategy 2015–2018, p. 43, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

The overall goal Civil Society Engagement is to broaden and deepen civil society engagement in OGP, both at a national and international level. The Civil Society Engagement team is available to support the whole community, but it prioritizes support to organizations and networks that wish to constructively engage in the OGP process.

OGP’s Peer Exchange strategy seeks to connect the government and civil society reformers across participating countries and create opportunities for them to learn from and inspire each other by exchanging ideas and technical support. This strategy complements the targeted support provided to participating governments and civil society organizations by the Direct Country Support and Civil Society Engagement teams. There are a number of examples where OGP has helped link reformers from different countries that are tackling a similar policy challenge. Behind the scenes, these interactions are becoming more regular and are strengthening OGP implementation. The Peer Exchange program will also seek to identify extremely successful initiatives from one country that might be ‘exported’ and adapted to work in other countries.

The Learning and Impact program has three objectives: (1) to provide the content that allows us to effectively share experiences, innovation and learning across the Partnership, including at regional meetings and events; (2) to ensure that, as an initiative, we are continuously learning and improving in order to provide better support to participating countries and civil society partners; and, (3) to develop ways of monitoring OGP’s progress and tracking impact, both at a country-level and at a global level. The Learning and Impact team will be responsible for regularly sharing what we learn from these three sets of activities with all OGP staff so that we continually adapt and improve our strategies based on what we are learning.

The IRM’s core function is to produce objective reports on each government’s progress toward achieving its OGP commitments. In doing this, OGP seeks to inform a country-level dialogue on results, with the goal of promoting both learning and accountability. Every year, an IRM researcher in each OGP participating country measures progress on the action plan and looks at how well a country has met OGP process requirements. Findings are published in a “Progress Report” which shows progress at the one-year mark (of a two-year action plan) and gives concrete recommendations to governments and civil society to improve the implementation of the current action plan and to design the next two-year action plan. Following the end of the second action plan, each IRM researcher (beginning in 2015) will publish a “Closeout Report” which gives the final status of each commitment at the 2-year mark.

The last core program component is the External Communications. OGP’s communications work to date primarily has focused on making information available on the OGP website, maintaining an active blog and social media channels, and ad hoc media opportunities such as at OGP events. In 2014 OGP is hiring a Senior Communications Manager to help develop and implement a comprehensive, four-year communications strategy identifying our target audiences, key messages, and priority activities. The strategy will cover both dissemination of OGP products and messages, as well as ways to solicit continuous input and feedback from key constituencies22. The table no. 1 summarizes the financial commitment to the core programs for next three years.

Table 1. OGP Projected Organizational Budget for 2015–2018

Source: Open Government Partnership, Four-Year Strategy 2015–2018, p. 44, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

***

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a voluntary, multi-stakeholder international initiative that aims to secure concrete commitments from governments to their citizenry to promote transparency, empower citizens, fight corruption, and harness new technologies to strengthen governance. In pursuit of these goals, OGP provides an international forum for dialogue and sharing ideas and experience among governments, civil society organizations, and the private sector, all of which contribute to a common pursuit of open government. OGP stakeholders include participating governments as well as civil society and private sector entities that support the principles and mission of OGP. OGP is not registered as an independent legal entity.

OGP participating governments are expected to uphold the values and principles articulated in the Open Government Declaration and to consistently and continually advance open governance for the well-being of their citizens. If a participating government repeatedly acts contrary to OGP process and to its action plan commitments, fails to adequately address issues raised by the IRM, or takes actions that undermine the values and principles of OGP, upon recommendation of the Criteria and Standards Subcommittee, the Steering Committee may review the participation of that government in OGP. It imposes on member countries to real defining the tasks of National Action Plans, as well as their implementation.

OGP has grown quickly in size since its launch in September 2011, to 65 participating countries as of May 2015. This reflects the momentum and interest in open government reform around the world, and the recognition of OGP as a voluntary vehicle for the government – civil society engagement and exchange of ideas. To maintain the organization’s credibility – and safeguard its long-term future – it is important that participating countries uphold OGP values and principles, as expressed in the Open Government Declaration and in the Articles of Governance.

Bibliography

Dates and Deadlines, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2014.

From Commitment to Action, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2014.

Mission and Goals, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Open Government Declaration, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Open Government Partnership (OGP) by the Numbers: What the IRM Data Tells us about OGP Results. Executive Summary of OGP IRM Technical Paper 1, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Open Government Partnership, Four-Year Strategy 2015–2018, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Open Government Partnership. Articles of Governance, April 2015, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Participating Countries, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

Requirements, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

1 Open Government Partnership (OGP) by the Numbers: What the IRM Data Tells us about OGP Results. Executive Summary of OGP IRM Technical Paper 1, p. 1, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

2 Open Government Partnership, Four-Year Strategy 2015–2018, p. 4, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

3 See: Mission and Goals, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015; Open Government Partnership, op.cit., p. 5.

4 See: From Commitment to Action, p.2, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2014.

5 Ibidem.

6 Open Government Declaration, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

7 Requirements, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

8 Open Government Partnership. Articles of Governance, April 2015, p. 17, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

9 See: Requirements, op.cit.; Open Government Partnership. Articles …, op.cit., p.12–13.

10 Requirements, op.cit.

11 See: Dates and Deadlines, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2014; Participating Countries, www.opengovpartnership.org, may 2015.

12 See: Open Government Partnership. Articles…, p. 6; Open Government Partnership, op.cit., p. 34.

13 See: Open Government Partnership. Articles…, op.cit., p. 7; Open Government Partnership, p. 34.

14 See: Open Government Partnership. Articles…, op.cit., p. 9–10; Open Government Partnership, op.cit., p. 34.

15 See: Open Government Partnership. Articles, op.cit.,, p.11; Open Government Partnership, op.cit., p. 35.

16 See: Open Government Partnership. Articles…, op.cit., p.12; Open Government Partnership, op.cit., p. 35.

17 See: Open Government Partnership. Articles…, op.cit., p. 12–13, 33–35.

18 See: Open Government Partnership…, op.cit., p. 8.

19 Ibidem, p. 9.

20 Ibidem, p. 10.

21 Ibidem, p. 15–16.

22 Ibidem, p. 18–27.