4(12)2016

Ewa Latoszek

Agnieszka Kłos

Warsaw School of Economics

The Eastern Partnership as a New Form

of the European Union’s Cooperation with the Third Countries1

Abstract

Since the 2004 enlargement the European Union has reiterated the need to deepen its relations with its eastern neighbours and work out a coherent European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) to maintain the relations with its eastern and southern neighbours. In March 2009 the European Council unanimously expressed its support for the ‘ambitious Eastern Partnership project which has become a part of its ENP and covered eastern neighbourhood countries. The aims and mechanisms of the Eastern Partnership are described in the joint declaration of the E. U. member states and the partner countries. The Partnership offers more to those who show greater progress in reforming their institutions to E. U. standards. According to the authors, the main benefit of this project is the progressive integration of the partner countries with the E. U. structures. The Eastern Partnership project was allocated a budget of 1.9 billion Euros for the 2010–2013 time period. That budget was approved by the European Commission and the money was committed through the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI). The sum includes the funds for the programmes and initiatives of the Partnership of multilateral character as well as the funds for cooperation with particular partner countries that meet the main goals of the EP.

Keywords: Enlargement, the Eastern Partnership, Neighbourhood Policy, dimensions of cooperation, EuroNest

Introduction

Following the enlargement of the European Union that included the countries of Central and Eastern Europe it seemed only natural to seek to ensure the stability and security of all member states. The European Union decided to develop positive and privileged relations particularly with neighbouring countries of the new member states. These relations were to be based on common values and standards of the European Union and were to be a mark of the effectiveness of the E. U.’s external policy. Thus a common E. U. policy towards the region was created, which was to show that, regardless of the ongoing debate in the E. U. on further enlargement to the East, the member states want to help their neighbours in carrying out reforms. In particular the Eastern countries were to play a prominent role within the E. U. policies. Located in the immediate vicinity, those post-Soviet republics had already been of concern to the Western European politicians for over 20 years. Already associated with the E. U. by bilateral political and economic agreements, they were now supposed to drift in the Western direction and undergo europeanisation, thus moving away from the Russian sphere of influence and becoming a buffer zone separating the E. U. from Russia [MFARP, 2011, p. 10]. The main goal of the paper is to analyse the background to the Eastern Partnership, its aims and costs and benefits for the countries involved as well as for the European Union. The research was conducted with the use of the following methods: a synthetic and deductive presentation of the essence of the concept of the Eastern Partnership, a critical analysis of foreign and Polish literature concerning the subject as well as a critical analysis of the documents concerning the subject matter. The research included also the quantitative analysis of various economic factors and a comparative data analysis.

The Origins and Initial Goals of the Eastern Partnership

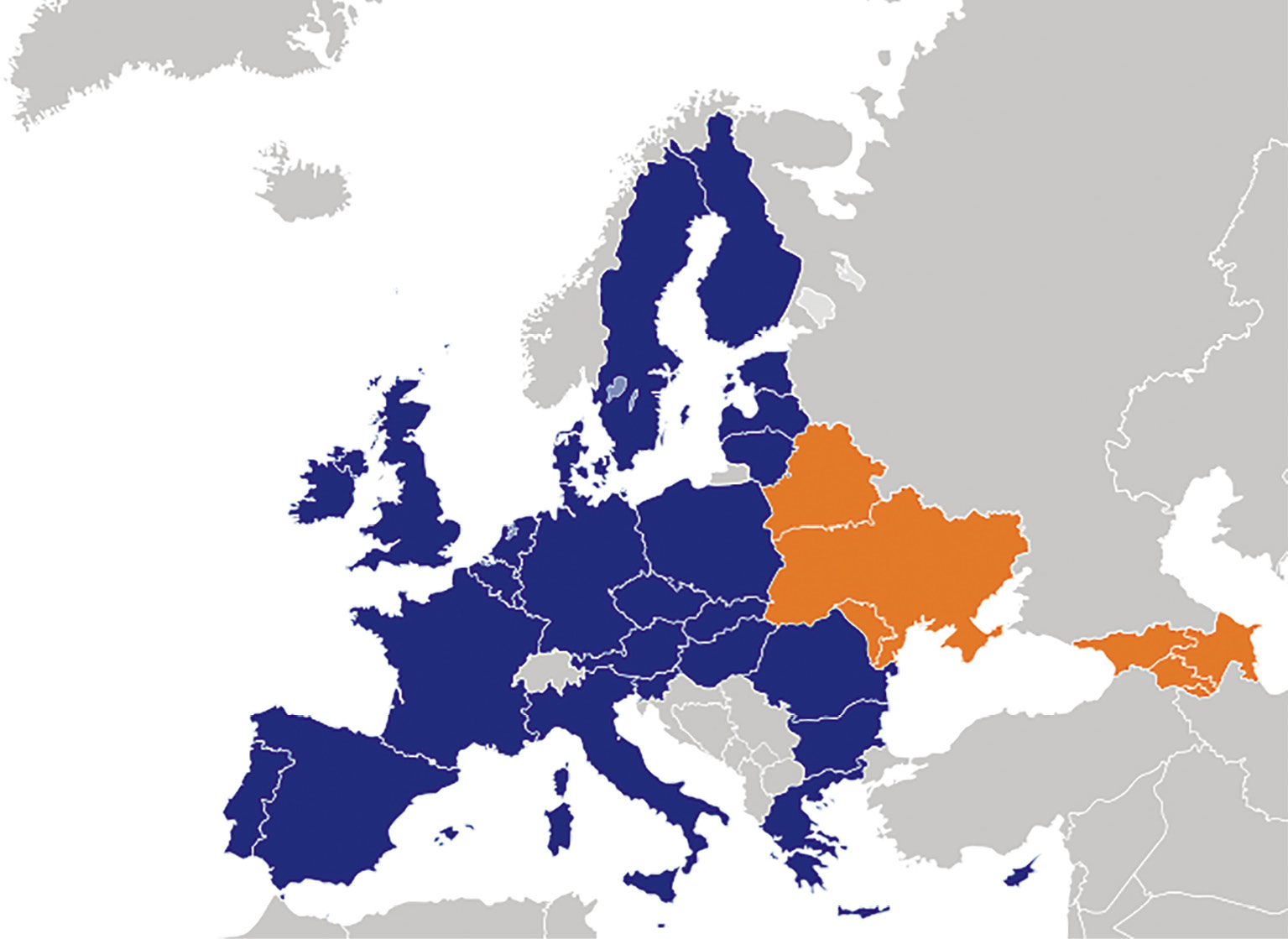

The creation of the E. U.’s common policy towards the Eastern Partnership countries was proposed by Germany, which during its presidency in 2007, suggested developing the European Neighbourhood Policy Plus. Soon after, Poland, with the support of Sweden, initiated the work on a project of a cohesive political initiative that would be addressed to Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine (see Illustration 1). As Poland had its concerns about a possible new division of Europe into privileged countries and those left behind, this common initiative was to be a clear signal that, regardless of the ongoing debate in the E. U. on the further enlargement to the East, the member states want to help their neighbours in carrying out reforms. In developing their project Poland and Sweden relied on the already existing European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) [MFARP, 2011, p. 10].

The ENP was launched in 2004 and applied to the countries of Eastern Europe, South Caucasus, North Africa and the Middle East (Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Moldova, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority, Syria, Tunisia and Ukraine). Another partner of the ENP is Belarus [Mongrenier, 2010], however, due to the lack of progress in democratisation and in respecting human rights the negotiations concerning the plan of action have never reached a conclusion. The areas of cooperation are many and include democratic reforms, market reforms, legislative reforms, border management, the media, environmental protection and non-governmental organisations. The idea behind creating the ENP was to blur the dividing lines between the new enlarged European Union and its neighbours and to foster prosperity, stability and security in the whole region. At the time the ENP was launched, it was expected that the countries that, as a result of the E. U.’s enlargement of 2004, would become its neighbours would strive to introduce democratic and market reforms. The state of affairs of the Eastern neighbours in lieu of the improvement would exacerbate. Ukraine suffered from an ongoing political turmoil; there was a recurring natural gas crisis in Eastern Europe; the authoritarian governments reigned in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Moldova (though in a less stringentmanner); undemocratic practices were exhibited by the Georgian authorities and, finally, the Russian invasion in Georgia in August, 2008. The effectiveness of the ENP in initiating changes in the Eastern neighbourhood fell below expectations. Although that is mainly because the very neighbouring countries did not show sufficient political will to introduce reforms, some part of the blame is also ascribed to the ENP project itself. That is what led some E. U. politicians to develop a new, more effective mechanism to stimulate the introduction of reforms in the Eastern neighbourhood [Ananicz, 2009, pp. 1–2].

A decision was made to launch a more ambitious initiative, the goal of which was to replace the existing selective support of reforms in Eastern Europe with a broad offer of comprehensive assistance in the process of modernisation and transformation. It was agreed that modernisation and transformation could only be achieved by the far-reaching economic and political integration of the partner countries with the E. U. In May, 2008 at the meeting of the E. U.’s heads of diplomacy, the foreign affairs ministers of Poland and Sweden, Radosław Sikorski and Carl Bildt, respectively, presented their project hoping it would win approval. Soon the project developed dynamically: only a month later, in June, 2008, the European Council adopted the project unanimously and called on the European Commission to draw up the details of the Polish-Swedish initiative. As a result, already in December, 2008 the European Commission put forwardspecific proposals concerning the Eastern Partnership project. In its official statement the Commission found that “stability, better governance and economic development on the Eastern borders are of vital interest to the European Union”. It also emphasised the key role that the member states that went through the transformation process had to play in the project. In March, 2009 the European Council unanimously expressed its support for the ‘ambitious Eastern Partnership project’. This meant that the project became an integral part of the European foreign policy. In the conclusions of the summit of March, 2009 the Council assured that the promotion of stability, good governance and economic development in the Eastern region was of strategic importance to the whole European Union.

Among the participants of the event there were also heads of the major E. U. political institutions, including the European Parliament and the European Commission, and the representatives of the financial institutions that offered support for the Partnership. The summit concluded with the leaders adopting the Prague Declaration, which became the basic founding document of the Eastern Partnership. The declaration holds that the Eastern Partnership is based on common interests and obligations and it will be developed jointly, in a fully transparent manner. The basis of the Eastern Partnership are the commitments concerning respecting the principles of international law and fundamental values such as democracy, the rule of law, human rights and fundamental freedoms/liberties as well as the free market economy, sustainable development and good governance [MFARP, 2011, pp. 10–11].

The Eastern Partnership introduces important changes to the hitherto existing ENP, such as:

“1. it differentiates the Eastern neighbours from the Southern ones and places the Eastern Neighbourhood on the orbit of the E. U.’s foreign policy as an individual entity. Up until then, the ENP mechanisms were the same for Eastern European countries as for countries of North Africa and the Middle East. Such lumping together of Eastern European countries with non-European countries lowered the profile of the E. U.’s and the Eastern European countries’ relations. Moreover, some of those countries saw it as a signal that their pro-E. U. aspirations had little chance of success. It also had a demotivating effect on the process of transformation. Most importantly, however, treating two so different regions as one impeded the E. U. on developing effective foreign policies towards its neighbours.

“2. it broadens and gives shape to the benefits offered to those partner countries that show progress in reforming their institutions according to E.U. standards. The main benefit should be a deepening integration of partner countries with particular E.U. structures; however, the extent of integration is largely dependent on individual aspirations and actual progress in the introduction of reforms” [Ananicz, 2009, p. 1].

The aims and mechanisms of the Eastern Partnership are described in the joint declaration of the E.U. countries and the partner countries. The Partnership offers more to those who show greater progress in reforming their institutions to E.U. standards. According to the authors, the main benefit of this project is progressive integration of partner countries with E.U. structures [EU, 2009]2.

Illustration 1. Map of the European Union and the Eastern Partnership

Source: K. Nieczypor [2013].

The Dimensions of Cooperation within

the Eastern Partnership

The Eastern Partnership assumes cooperation in the following dimensions: bilateral, multilateral and intergovernmental (Table 1).

The objective of the bilateral dimension of the Eastern Partnership is to bring forth a new legal basis for the relations between the E. U. and its Eastern neighbours in the form of association agreements and to create Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas. The initiative envisages taking actions towards a visa-free regime and cooperation regarding energy security.

The multilateral dimension of the Eastern Partnership is supposed to support the political and economic changes in the partner countries, thus becoming a forum for the exchange of information and experiences at the level of heads of state and heads of government, foreign affairs ministers, high-ranking officials and experts. The multilateral dimension encompasses four thematic platforms within which meetings are held, i.e.: democracy, the rule of law and stability; human relations; economic integration and convergence with the E. U. sectorial policies; security. Within the multilateral dimension the Eastern Partnership has launchedthe so-called flagship initiatives, which involve the actions that are to make the Partnership project more concrete and tangible as well asto give it visibility in the international arena.

The cooperation within the so-called “non-governmental dimension” includes, among others,: the Parliamentary Assembly EuroNest, a forum for dialogue between the European Parliament and the representatives of the parliaments of the partner countries; the Civil Society Forum of the Eastern Partnership, which brings together the representatives of non-governmental organisations and other bodies from the third sector from the E. U. and from the partner countries; and the Business Forum of the Eastern Partnership, which is a meeting point for the representatives of business organisations, entrepreneurs, government representatives and the representatives of the institutions from within the E. U. and from the partner countries. Implementing the Eastern Partnership is also an aim of the Committee of Regions, which is in charge of organising the Going East forum and which supervises the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities for the Eastern Partnership – a platform for cooperation between local authorities of the E. U. and regional and local authorities of the partner countries [Szeligowski, 2013].

The Eastern Partnership is not an office or an institution; it is a project of multilateral dimensions that is a forum for the exchange of information and experiences between the partner countries. Every two years, on a regular basis, meetings of the partner countries are held, which is where the heads of state and government of the member states of the European Union set the main course within the Eastern Partnership. Each year, ever since May, 2011, foreign affairs ministers (the Parliamentary Assembly EuroNest) meet in order to evaluate the progress made in executing the joint projects and draw up directions for further actions. The officials directly responsible for the reforms in particular sectors meet twice a year. The meeting takes place in Brussels and is led by the European Commission. Those meetings have been taking place since June, 2009 and are grouped into four thematic platforms [MFARP, 2012, p. 11]:

•democracy, the rule of law and stability (the respecting of human rights, the market economy). This platform encompasses areas such as: integrated border management, fighting corruption and administration reform,

•economic integration and convergence with the E. U. sectorial policies. The meeting within this platform concerns issues such as support for small and medium-sized enterprises, support for trade, environmental protection and climate change,

•energy security,

•contacts between people, culture, education, science [MFARP, 2012, p. 11].

The platform on democracy, the rule of law and stability relates to issues such as the reform of civil service, the fight against corruption, cooperation in justice and police matters, security issues, the freedom of the media and standards for elections.

The platform on economic integration and convergence with the E. U. sectorial policies incorporates the following issues: economy and trade, sectorial reforms, the socio-economic development, equal opportunities, healthcare, environmental protection and climate change, reducing poverty reduction and social exclusion.

The platform on energy security deals with the harmonisation of energy policies and the alignment of regulations of the partner countries to the E. U. standards and practices.

The platform on contacts between people facilitates and enhances the following: cultural cooperation, the NGOs support, student exchange programmes, joint media projects and the incorporation of the partner countries into the research programmes framework.

The meetings should lead to adopting realistic and important new goals for the cooperation in question. In between the planned meeting panels, setting goals and designing the ways to achieve them for each platform can take place (the Eastern Partnership Multilateral Platforms) [EC, 2011].

The Parliamentary Assembly EuroNest3 is responsible for the multilateral parliamentary dialogue. It is a forum for consulting, controlling and monitoring of all the issues regarding the Eastern Partnership. The goal of EuroNest is to bring about actual support for and the strengthening of the Eastern Partnership within the abovementioned four thematic platforms. The Assembly is composed of the members of the European Parliament and members of parliament from all of the partner countries. EuroNest appoints four parliamentary committees, the scope of which corresponds to the four thematic platforms; it also passes resolutions, recommendations and opinions4.

Table 1. The Dimensions of Cooperation within the Eastern Partnership

|

Bilateral dimension |

Multilateral dimension |

Non-governmental dimension |

|

1. Supporting of reforms 2. Association agreements 3. Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas 4. Mobility and security 5. Energy security 6. Support of social and economic development |

1. Thematic platforms: 1.1. Democracy, good governance and stability 1.2. Economic integration and convergence with the E. U. sectorial policies 1.3. Energy security 1.4. Contacts between people 2. Flagship initiatives: 2.1. Program of integrated border management 2.2. Support for the development of small and medium-sized enterprises 2.3. Regional electricity markets, energy efficiency and renewable energy sources 2.4. Environmental governance 2.5. Prevention, preparedness and response to natural and man-made disasters |

1. Parliamentary Assembly EuroNest 2. Civil Society Forum of the Eastern Partnership 3. Congress of Local and Regional Authorities 4. Business Forum of the Eastern Partnership |

Source: D. Szeligowski [2013].

Some doubt the EuroNest will play a significant role in the E. U. It is an institution with no decision-making competencies that gives recommendations and passes resolutions, it is responsible for the dialogue between the members of the European Parliament and the members of parliaments of the partner countries. The countries of the Eastern Partnership, however, are not interested in the operations of EuroNest and do not see any added value in it [Łada, 2011]. The first session of EuroNest, which took place in September, 2011, was a big disappointment. The plan assumed adopting two documents whilst the session ended with no agreements made and no identifiable conclusions or outcome. Those documents concerned the projects of recommendations for the Eastern Partnership summit (late September, 2011 in Warsaw) and declarations on the subject of Belarus. The debate was interrupted by a heated dispute between the group of Georgians, Azeris and Armenians.

The failure of 2011 did not mark the ending to EuroNest and the Assembly is still functioning. It is there to keep the E. U. interested in its Eastern neighbourhood. It can also serve as a case study for the Eastern Partnership. Encouraging the partner countries to develop multilateral cooperation will be extremely difficult, especially in the Caucasus region. What the partner countries are counting on is financial aid and visa facilitations. The key elements of the Eastern Partnership are the support for civil society and educating the youth. Only the new generation can truly part with the facade democracies and chauvinism-ridden disputes [Szczepanik, 2011].

The Eastern Partnership – the Viewpoints of the Partner Countries and the European Union

The Eastern Partnership was subject to evaluation and opinions given by the representatives of both partner countries and the E. U. since its foundation. The evaluation had to do with a possible enlargement of the European Union. France and Germany saw the Partnership as a substitute forthe further enlargement of the E. U. whilst Poland called it the first step on the path to enlarging the E. U. to entail the partner countries.

A bone of contention was the division of competences between the Partnership and other regional initiatives: the Black Sea Synergy and the Northern Dimension. Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece fear that the Partnership might lower the profile of the Black Sea Synergy, which to them is of more value than the Partnership. The Black Sea Synergy is an initiative of the European Commission dating back to 2007. It incorporates the countries of the Black Sea: Bulgaria, Georgia, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine, together with Armenia, Azerbaijan and Greece. The aim of the Black Sea Synergy is to stimulate regional cooperation in the Black Sea basin in areas such as energy, transport, environmental protection, the movement of citizens and security. The Synergy is based on three main processes: the ENP, strategic partnership of the E. U. with Russia and Turkey’s accession process. The Northern Dimension wasinaugurated in 2009 and initiatedby Finland. It incorporates Iceland, Norway, Russia, and the E. U. The goal of the Northern Dimension is to develop cooperation in the European arctic and subarctic regions, mainly the basins of the Baltic Sea, the Barents Sea and the Arctic Sea [Popielawska, 2009].

Ukraine called the Eastern Partnership a step towards membership in the E. U. and emphasised its support for launching specific reforms (e.g. of the energy sector). Belarus was hoping for exports facilitation, foreign investments and loans and some visa facilitation scheme in the Schengen Area. The president of Moldova expressed his disappointment with the lack of prospects for the E. U. membership, but he also expressed hopes for signing an association agreement. The countries of the South Caucasus were pleased with the Eastern Partnership since the very beginning, although Azerbaijan, for various reasons, was mostly interested in cooperation in the area of energy. Armenia was hoping to sign an association agreement with the E. U. It would seem that of all the South Caucasus countries it was only Georgia that was ready for the increased cooperation with the E. U. within the Partnership. The Georgian President called the Eastern Partnership an “elegant response on the part of the E. U.” to the Russian-Georgian war that took place in September [OSW, 2009]. Another matter is the reaction of the Russian Federation, which was not part of the Eastern Partnership. Its authorities, on more than one occasion, expressed discontent with the Partnership. What the E. U. saw as a socio-economic project, Russia perceived as a political or even geo-strategic initiative [Jankowski, 2009, p. 47].

The notions behind the Eastern Partnership were highly ambitious, but not really adapted to the political and economic climate in Europe and in the world. The main objective of the Partnership was to “create the necessary conditions to accelerate the process of political association and further economic integration between the E. U. and its Eastern neighbours”. However, the authors and signatories of the Prague Declaration should not be blamed for the fact that those conditions have worsened due to the economic problems in the world and the sovereign debt crisis in the Euro zone, or for the difficulties the partner countries encountered while introducing the principles of good governance. This is to say that a tangible improvement in the relations between the E. U. and the Eastern Partnership countries – the bringing of those relations to a higher level as envisaged by the leaders at the meeting in Prague in 2009 – is yet to be seen. The success of the Partnership is largely dependent on the access to funds. Achieving the standards of living similar to that of the E. U. and making the developmental leap forward is a difficult task. Another issue is the effectiveness of the programmes and projects in progress, which causes the E. U. to give actual support to positive trends in the Eastern countries, especially supporting their economic and social growth and their democracies, the respecting of human rights and good governance [Bagiński, 2011, p.p. 1–2].

The success of the Georgian reforms will be an indicator of the effectiveness and credibility of the Eastern Partnership programme. It is key that the E. U. participates in the process of democratisation in Georgia and provides expert and financial assistance.

The E. U. has a significant influence over the reforms in the country and should put more emphasis on the principle of conditionality and be firmer in criticising the Georgian authorities whenever the rule of law and democracy are infringed [Sikorski, 2011b].

According to some experts who criticise the E. U. for overly bureaucratic procedures, after four years since the launching of the Eastern Partnership project, many people do not see it as a factor that influences their lives5.

Each year the European Union prepares the European Integration Index for Eastern Partnership Countries (EaP Index), which is a tool for monitoring civil society and it measures the pace of integration of the Eastern Partnership countries. This index was designed to keep the partner countries on the path of development and warn them if they stray from the expected path of progress. The Index has three main aspects. First, it takes the idea of sustainable democracy seriously, setting out detailed standards for its assessment. Second, the Index provides a cross-country and cross-sector picture and allows for their comparative analysis6. Third, the Index bolsters the already existing E. U. efforts, such as the annual progress report, by offering an independent analysis of the Eastern Partnership countries. The Index interprets the ‘progress in European integration’ as a combination of two separate yet interdependent processes: the increased linkages between each of the EaP countries and the European Union as well as the approximation between those countries’ institutions, legislation and practices and those of the E. U. While the first process reflects the growth of political, economic and social interdependencies between the EaP countries and the E. U., the second process shows the degree to which each EaP country adopts the institutions and policies typical of E. U. member states and required of the EaP countries by the E. U. The Index showcases the significance of the increased linkages and greater approximation in the process of achieving goals. Its dynamics, however, depend on political decisions. This led to the defining of the following three dimensions for evaluation [IRF/OSF/EPCSF, 2013]:

•Linkage: denotes the growing political, economic and social ties between each of the six partner countries and the E. U.;

•Approximation: shows the structures and institutions in the partner countries converging towards the E. U. standards and in line with the E. U. requirements;

•Management: denotes evolving the management structures and policies for European integration in the partner countries [IRF/OSF/EPCSF, 2013, p. 12].

Each year the 2013 Index shows progress of all the six Eastern Partnership countries in the alignment with the European Union, with some exceptions. The different starting points, the different ambitions and a different pace of reforms result in the different evaluations and different positions of the six countries.

Moldova is the best reformer in the region and is the closest one to meet the E. U. standards. The country has improved its score in the ‘approximation’ and ‘management’ dimensions. It is the top performer in all three dimensions and has the highest score on deep and sustainable democracy.

Georgia is the second best performer according to the Index. The country has improved its scores in all three dimensions. It is in the second place in the ‘approximation’ dimension and it also had exactly the same score as Moldova in ‘management’. Among the Eastern Partnership countries Georgia made considerable progress last year (that is in 2012) in building deep and sustainable democracy.

Ukraine, the third performer overall, is a frontrunner in political dialogue, trade, economic integration and sectorial cooperation with the E. U. However, the country does not take full advantage of its geographic proximity to the E. U. and its privileged relations to better converge withthe E. U. standards. Compared to the standing in 2012, Ukraine has slightly dropped in the ‘linkage’ dimension and slightly improved in ‘approximation’, with the ‘management’ score remaining at the same level.

Armenia has made considerable progress in 2013 on its path towards the E. U. The country has improved its results across all the three dimensions, especially in ‘management’ where it scored almost as high as Ukraine.

Azerbaijan ranks fifth in all the dimensions of the Index. Although the country has improved in ‘linkage’ to E. U., there has been no progress in ‘approximation’ and even a slight drop in the ‘management’ dimension.

Belarus seems the farthest away from the E. U. It ranks last in all the three dimensions of the Index. However, though there has been no change in ‘linkage’, Belarus has in fact improved its scores both on “approximation” as in “management” [IRF/OSF/EPCSF, 2013, p. 16].

The Funding of the Eastern Partnership

The Eastern Partnership project was allocated a budget of 1.9 billion Euros for the 2010–2013 time period. That budget was approved by the European Commission and the money was committed through the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI). The sum includes the funds for the programmes and initiatives of the Partnership of multilateral character as well as the funds for cooperation with particular partner countries. The money from the ENPI is to serve three basic goals:

•assisting the process of political transformation in the partner countries and their stride towards a democratic rule of law (including promoting human rights),

•assisting the process of creating market economies in those countries,

•promoting sustainable development.

The projects of the Eastern Partnership are also funded through other financial mechanisms of the European Union. The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights focuses on the projects that support and promote civil society and human rights. The Neighbourhood Investment Facility (NIF) supports investments in infrastructure for the energy and transport sectors, environmental protection and the development of the private sector (especially small and medium-sized enterprises) and the social sector. The European Commission allocated 700 million Euros to the NIF for the period between 2007 and 2013. What is more, international financial institutions have been increasingly participating in the funding of the Eastern Partnership – in particular the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. In 2010 the EIB launched the Eastern Partners Facility programme with a total budget of 1.5 billion Euros to be allocated to loans and guarantees for investments in the partner countries. Entrepreneurs can apply for those funds directly at the European Investment Bank.

On December 1st, 2011, the European Council on Foreign Relations created the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Its goal is to assist democratic transformations and it operates primarily through allocating funds to partner organisations (political foundations, non-governmental organisations etc.) for the actions envisaged in the fund’s mission. The European Endowment for Democracy will be funded from the European budgets and from the contributions from the member states of the E. U. Another instrument for supporting the civil society in the neighbour countries is the Neighbourhood Civil Society Facility (NCSF). NCSF’s aid is supposed to strengthen democratisation (i.a. throughthe strengtheningof the role of non-governmental organisations and promoting pluralism in the media or election observational missions), including developing civil society and its involvement in political dialogue. For the 2011–2013 time period the NCSF was allocated a budget of 22 million Euros from the ENPI (to be distributed evenly between the Southern and Eastern neighbourhood policies). Funds can also be obtained from outside the E. U. The programmes can be co-financed through the funding committed by the member states, the states of the European Economic Area (EEA), international organisations and enterprises and other economic entities [Eastern Partnership, MFARP, 2011, pp. 39–40].

The EU’s budget for the 2014–2020 time period introduces certain modifications in the funding mechanisms, including the funding of the Eastern Partnership. Starting from 2014 the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) will be replaced with the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI), which will be the main source of funding for the countries of the Eastern Partnership. The new instrument will, to a larger extent, meet the political needs by giving more diversity and more flexibility while at the same time applying more rigid selection criteria but offering a wider set of benefits to the best performers [Taczyńska, 2013, p. 22]. The European Neighbourhood Instrument has envisaged a budget of 15 billion Euros for the Eastern Partnership in the years 2014–20207.

Poland’s Involvement in the Development

of the Eastern Partnership

When Poland opened its membership negotiations with the European Union in 1998, its goal was to create an Eastern dimension of the E. U.

While actively participating in the Convention on the Future of Europe, Poland was constantly lobbying for the Eastern partners. It also undertook a series of actions itself, such as the abolition of visa fees for the Ukrainian citizens and the bringing forth of the so-called Riga initiative8. To develop a common policy, Poland tried to use its leadership in the Central European Initiative. Already at that time it proposed following a coherent policy towards the Eastern European countries and one that would be flexible enough to ensure individual relations with each of the countries, indicating that they would not only focus on political and economic integration, but they would also exhibit a clear human and social dimension. After the enlargement of the E. U. to the East, many Eastern neighbours feared that it would create a new wall dividing the continent into privileged countries and those that have to cope with their problems themselves. Poland has taken many measures showing that it would use its membership in the E. U. to effectively promote positive changes in the countries of Eastern Europe: it is actively involved in the implementation of the Eastern Partnership and it has been working to enrich this initiative with new elements and additional support for the societies of the partner countries. In January, 2010 in Madrid, together with Spain holding the Presidency of the European Union, the Polish authorities held an international seminar on the Eastern Partnership. Many new ideas for additional support for the modernisation of the E. U.’s Eastern neighbours were put forward; among those was the establishment of the Group of Friends of the Eastern Partnership (today known as the Information and Coordination Group). Its creation was agreed in May 2010 in Sopot, at an informal meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the European Union and the Easter Partnership countries, which was convened at the initiative and invitation of the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland, Radosław Sikorski. This informal group is to be a forum of cooperation with non-members of the E. U. interested in supporting the Eastern Partnership, such as the United States of America, Norway, Japan, Canada, Switzerland, Russia, and Turkey. Some of those countries are ready to act as donors and provide financial support to the E. U. initiative. Others, especially those located in the vicinity of the Eastern Partnership countries, are willing to participate in some projects. The Polish government allocates a large share of its foreign aid funds to the meeting of the Eastern Partnership goals (in the years 2010 to 2011 a total of almost 100 various projects in the partner countries were in progress). The Eastern Partnership was also one of the main priorities of the Polish Presidency in the second half of 2011. Poland constantly sought to strengthen the Eastern dimension within the neighbourhood policies through deepening sectorial cooperation and including the Eastern Partnership countries in the cooperation in the programmes and with the E. U. agencies. During the second Eastern Partnership Summit in Warsaw on September 29th and 30th, 2011 a Common Declaration (called “Varsavian”) was adopted. It was a strong political sign of deepening integration and the further involvement of the E. U. and its Eastern partners in joint initiatives. The text included specific declarations of the willingness to actively cooperate such as emphasising that that Partnership in based on shared values, the acknowledgement of the European aspirations of the partner countries, their declaration of readiness to integrate with the E. U.’s inner market and, in the future, their willingness to create a common economic area of the E. U. and the Partnership countries. This declaration confirmed the strive towards a visa-free regime and the deepening of sectorial cooperation. The Warsaw Declaration also announced the future opening of the E. U. programmes for partner countries’ citizens and marked the year 2011 as a possible date of closing the negotiations on the association agreement with Ukraine and launching the negotiations with Georgia and Moldova on Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTA). Also during the summit in Warsaw the Eastern Partnership Academy of Public Administration (EPAPA) was founded as a multiannual programme of training sessions for officials representing the partner countries. As envisaged in the Declaration, the DCFTA negotiations with Georgia and Moldova were launched and the negotiations on the EU-Ukraine association agreement were concluded. Poland has also managed to successfully bring forth the creation of the Eastern Partnership Business Forum (the founding meeting took place in Sopot). The Presidency also gave support to the organisations of the Third Forum of Civil Society in Poznań, which hosted the inauguration meeting of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities for the Eastern Partnership. It was also during the Polish Presidency that the first official meeting of the Parliamentary Assembly EuroNest took place. With the goal to deepen sectorial cooperation of the Eastern Partnership, the Polish Presidency held a series of meetingsat the level of ministers, high-ranking officials and experts, among those there were: conferences ofthe Ministers of Economy, Transportation and Agriculture, a debate of the Ministers of Higher Education, conferences of the Heads of Customs Chambers and a meeting of the Heads of Statistical Offices, expert conferences on migration, fighting drug-related crime and human trafficking, climate cooperation, fighting corruption, energy, security, education, culture, customs and industrial property. Based on the Polish initiative the European Commission is currently working on designing a further development scheme of the sectorial cooperation. For example, it created the ‘road map’ for the effective implementation of the Eastern Partnership in the period preceding the Partnership’s summit in the autumn of 2013 [Eastern Partnership, MFARP, 2011, pp. 43–45].

Conclusions

The Eastern Partnership initiative has created a framework and mechanism for the integration of the EaP countries with the European Union. Unfortunately, it has not gained any major political significance that would match the European Union’s ambitions and the challenges ahead of it. Moreover, the impact of the initiative has turned out to be limited because of the clashes of interests among the parties involved (the E. U. institutions, E. U. Member States and the Partner countries). The progress of transformation in the neighbouringcountries has fallen short of expectations, which revealed major limitations of the E. U. and the instruments it has been using to foster change. The European Union has failed to become a change agent in the region to the extent that would match its ambitions. The structure and bureaucratic instruments developed within the framework of the European Neighbourhood Policy and the Eastern Partnership cannot quickly respond to the dynamic political processes taking place in Eastern Europe and in the E. U. itself. In this situation, the real political significance of the Eastern Neighbours integration with the European Union has diminished and the process itself is dominated by bureaucratic procedures. The parties involved are interested in maintaining dialogue rather than makingquantifiable progress in the integration with the E. U.

Under the European Union’s foreign policy, including the Eastern Partnership, reaching internal consensus takes more time and effort than can be devoted to achieving tangible outcomes outside the European Union. Where there is no political willingness to pursue deeper integration with its neighbours, or unanimity about the long-term objectives of integration, then the strategic decisions and the delivery of specific commitments (such as establishing the visa regime) can be postponed. The Partner countries, on the other hand, can abuse this situation in their internal affairs to avoid paying the high political and economic price of implementing real reforms and making the transition, and externally to pursue a policy balancing between the E. U. and Russia. Currently, a breakthrough in the multilateral relations seems unlikely to happen in the short term. The E. U. refuses to redesign its policy towards the neighbours until it manages to streamline its decision-making process and make a choice about the future direction of its development. Moreover, the situation in the Eastern Neighbourhood seems to be so unstable at the moment that the E. U. – being, on the one hand, forced to pursue a more active policy – cannot find the best way to act in the best interests of all its Member States.

Bibliography

Ananicz Sz. [2009], Eastern Partnership, Bureau of Research of Chancellery of the Sejm, no. 17 (64), http://orka.sejm.gov.pl/WydBAS.nsf/0/8567007B249862DEC12576350035AB90/

$file/Infos_64.pdf (in Polish).

Bagiński P. [2011], Wspieranie rozwoju krajów Partnerstwa Wschodniego: czy powinniśmy zaoferować więcej?, Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego, Warsaw.

EC [2011], Eastern Partnership Multilateral Platforms. General Guidelines and Rules of Procedure, European Commission Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/eastern/platforms/rules_procedure_en.pdf (17.05.2014).

EC [2014], Eastern Partnership, European Commission, http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/

what-we-do/policies/international-affairs/eastern-partnership/index_en.htm (17.05.2014).

EU [2009], Joint Declaration of the Prague Eastern Partnership Summit, Prague, 7 May 2009, 8435/09 (Presse 78), Council of the European Union, Brussels, May 7, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_PRES-09-78_en.htm

http://oide.sejm.gov.pl/oide/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14731&

Itemid=784 (17.05.2014).

http://oide.sejm.gov.pl/oide/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14781&

Itemid=831 (17.05.2014).

http://www.euractiv.pl/rozszerzenie/artykul/partnerstwo-wschodnie-nie-przynioso-rezultatow-004570 (17.05.2014).

http://www.euronest.europarl.europa.eu/euronest/cms/home/gendocs (17.05.2014).

IRF/OSF/EPCSF [2013], European Integration Index 2013 for Eastern Partnership Countries, International Renaissance Foundation in cooperation with the Open Society Foundations and Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum, http://www.eap-index.eu/sites/default/files/EaP_Index_2013_0.pdf (17.05.2014).

Jankowski D. [2009], Rozdrażniony niedźwiedź, „Nowa Europa Wschodnia”, no. 5, http://www.new.org.pl/166, artykul.html (17.05.2014).

Łada A. [2011], EURONEST As a Euro-problem, Institute of Public Affairs (Instytut Spraw Publicznych), April 4, http://www.isp.org.pl/programy,program-europejski,projekty,wspolpraca-z-parlamentem-europejskim,737.html (17.05.2014).

MFARP [2011], Eastern Partnership, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland, http://eastern-partnership.pl/pw_pl/MSZ%20PW%20PL.pdf (17.05.2014) (in Polish).

MFARP [2012], Poland’s Development Co-operation and the Eastern Partnership (2009–2010), Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland, http://www.polskapomoc.gov.pl/files/dokumenty_publikacje/PUBLIKACJE_2011/projekty_polska%20pomoc_w_krajach_PW_2011.pdf (17.05.2014).

Mongrenier J. S. [2010], Eastern Europe is a Long Term Challenge, in the Debate: Belarus-EU: A Cold Neighbourhood?, http://www.easternpartnership.org/community/debate/eastern-europe-long-term-challenge (17.05.2014).

Nieczypor K. [2013], Trwa nieformalne spotkanie krajów Partnerstwa Wschodniego w Tbilisi, http://eastbook.eu/2013/02/country/georgia/trwa-nieformalne-spotkanie-kraj%C3%B3w-partnerstwa-wschodniego-w-tbilisi/ (17.05.2014).

OSW [2009], Reactions to the Inaugurational Summit of the Eastern Partnership, “A week in the East. A bulletin analysis (Biuletyn Analityczny OSW)”, no. 18 (93).

Popielawska J. [2009], Perfect Together? Eastern Partnership in the Context of other EU Initiatives in the East, “Analizy Natolińskie”, no. 6 (38).

Sikorski T. [2011a], Armenia and Azerbaijan and their Eastern Partnership, “Biuletyn”, no. 63, Polish Institute for International Affairs, http://www.pism.pl/files/?id_plik=7605 (17.05.2014).

Sikorski T. [2011b], Eastern Partnership in Georgia: Initial Results, “Biuletyn”, no. 19, Polish Institute for International Affairs, http://www.pism.pl/files/?id_plik=5842 (17.05.2014).

Szczepanik M. [2011], Eastern Partnership: The Failure of EURONEST, http://wyborcza.pl/prezydencja2011/1,111800,10305362, Partnerstwo_Wschodnie_porazka_Euronestu.html (17.05.2014).

Szeligowski D. [2013], Eastern Partnership. Effectiveness Analysis: Ukraine Case Study, WSIiZ Working Paper Series, http://workingpapers.wsiz.pl/pliki/working-papers/Szeligowski_WPS%204_102013.pdf (17.05.2014) (in Polish).

Taczyńska J. [2013], The Cooperation of Polish Local Authorities with Regional and Local Authorities and other Entities of the Eastern Partnership, WPiA University of Lodz, Lodz, http://www.umww.pl/attachments/article/34141/Partnerstwo%20Wschodnie%20%E2%80%

93%20Samorzady.pdf

1 Reprint of an article: E. Latoszek, A. Kłos, Eastern Partnership as a New Form of the European Union’s Cooperation with Third Countries, ed. T. Muravska, A. Berlin, From Capacities to Excellence Strengthening Research, Regional and Innovation Policies in the Context of Horizon 2020, University of Latvia Press, pp. 28–43.

2 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/PL/er/107647.pdf (17.05.2014).

3 For more on EuroNest, http://www.euronest.europarl.europa.eu/euronest/cms/home/gendocs (17.05.2014).

4 http://oide.sejm.gov.pl/oide/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14731&Itemid=784 (17.05.2014).

5 http://www.euractiv.pl/rozszerzenie/artykul/partnerstwo-wschodnie-nie-przynioso-rezultatow-

004570 (17.05.2014).

6 The six countries are evaluated based on the same list of questions and indices (a total of 823 measures).

7 http://oide.sejm.gov.pl/oide/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14781&Itemid=831 (17.05.2014).

8 It is a broad regional cooperation initiative of 17 countries to support the processes of transformation and the joint fight against crime and terrorism.